a Marxist analysis of “My Last Duchess”

advertisement

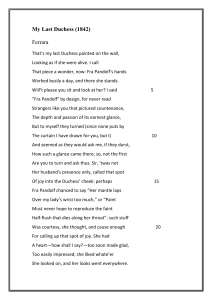

Jason Field ENG251 Grant, Kendall My last dowry: a Marxist analysis of “My Last Duchess” “My Last Duchess” is a poem by Robert Browning that takes place in Ferrara, Italy, between the 14th and 17th Century. This was during the Renaissance period; commonly remembered as a particularly “Golden Age” for free-thinkers, and artists and art enthusiasts of many different forms. Those who were able to own or purchase any of these works of art were usually the higher-ups in Society. However, as we see clearly in “My Last Duchess,” works of art were not the only things that people commodified for their exchange, or sign-exchange value. The narrator of the poem, the Duke, has a consistent habit of following the capitalist ideology of commodification: treating the things he “owns” as commodities, especially his “last Duchess,” and his Duchess soon-to-be, due in part to his own socioeconomic standing, reinforced by the ideology of classism. The way the Duke both views and uses this socioeconomic standing is a classic example of both the ideology of classism, and his role as a Bourgeoisie. Generally speaking, the title of “Duke” itself is enough for people to understand what level of Society someone is at, and just what kind of wealth and financial power that person has. However, the Duke in “My Last Duchess” not only accepts his place in the aristocracy, but also constantly flaunts it! Classism is defined as “equating one’s value as a human being with the social class to which one belongs.” In other words: the higher up on the social ladder you are, the smarter or better as an individual you tend to view yourself. The main way the Duke flaunts his standing is in his blatant commodifying of everything he owns. This is initially seen at the beginning of the poem when he first introduces us to the painting of “[his] last Duchess” (1). Not only does he find it necessary to mention the name of the painter hired for the portrait, Frà Pandolf, (3) but does so again merely a few lines later, pointing out that he brought up the painter’s name on purpose, or, as he puts it, “by design” (6). Since such a statement does not serve to increase the use value of the painting for us, the only reason I can see for this is that the Duke has placed a personal sign-exchange value on the painting. Sign-exchange value is to value an object for the way it transfers a type of social status to its owner. In other words, the only value in the object is how “good” or important it makes someone appear by simply possessing it. By saying and repeating the painter’s name the Duke is attempting to reinforce the importance and value on the painting, and thereby the importance and value on himself as the owner of it. He also makes sure that the mysterious person he’s addressing doesn’t misunderstand the importance, insisting that he take the time to “sit and look at her” (5). He then continues this display of social self-importance by pointing out how others have asked about the painting before. By doing this, he not only relays a sense of superiority in his knowledge about the painting, but also shows the reader how possessive he is about it. The parenthetical line “… (since none puts by / The curtain I have drawn for you, but I),” (9-10) is an unspoken statement directed at the painting itself, and reveals that he feels as if he, and he alone, is the only person who is allowed to show and explain the painting to others; the painting is his, it belongs to him, and he is the owner. The fact that no one else is allowed to even view the painting without his permission is just a further testament to the high level of sign-exchange value he has placed on it. When talking about the history behind the painting itself, specifically the “spot of joy” on the Duchess’ cheek, he concludes that it must have been some outside influence to his own that caused her to blush: “Sir, ‘twas not / Her husband’s presence only, called that spot / Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek…” (13-15). He further suggests that it may have been caused by a comment from the painter himself. What is remarkably interesting is that, in doing so, he suggests that the type of comments from the painter might have been something, which would seem, to have been said purposefully to draw out a smile or blush from the Duchess: … perhaps Frà Pandolf chanced to say ‘Her mantle laps Over my lady’s wrist too much,’ or ‘Paint Must never hope to reproduce the faint Half-flush that dies along her throat:’ (15-19) In other words, the word-choice of the painter was such that he wanted to get the Duchess to smile or blush. Why? Given that we are still in the mind and imagination of the Duke himself as this scene is “taking place,” it is quite likely that his reasoning for the painter in doing so would be to increase the exchange value of the painting he was creating. Exchange value is simply a value placed on something based on what it can be traded or sold for (in this case, likely money). Why not? After all, a painter would know what types of paintings and what particular details were of more monetary worth, would he not? And, since this is the mind of the Duke, who consistently tends to commodify things, would it not make sense to him for others to do the same? Regardless, the Duke appears very upset by his wife’s apparent response to this possible situation, claiming that “She had / A heart -- how shall I say? -- too soon made glad, / Too easily impressed;” (2123). It is starting from here in the poem that we begin to get a better idea of the relationship that existed between the Duke and the Duchess. And, from the Duke’s perspective, it is enlightening indeed. He continues to explain his frustration at his wife for being “too easily impressed” by everything: “She liked whate’er / She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.” (23-24). However, it is in the following line that we start to get an idea as to why this would upset him so much: “Sir, ‘twas all one!” (25). Or, in other words, “There was no difference!” Given what we already know about the Duke and his belief in the classist ideology, is it any wonder then that he would consider it so offensive the fact that she seemed to treat all gifts and “niceties” from others in equal measure, regardless of the socioeconomic status of the giver? “all and each / Would draw from her alike the approving speech, / or blush at least.” (29-31) One of these he mentions is a “bough of cherries” given to her by some “officious fool” (27). The online Oxford dictionary defines “officious” today as: “assertive of authority in an annoyingly domineering way.” But, this definition does not seem to fit at all the Duke’s classist view on what “authority” is. The Oxford dictionary goes on to reveal that the origin for this word was derived in the late 15th century from a Latin phrase “officiosus” which means, “obliging,” and the original definition was: “ready to help or please.” The term then became depreciatory in the late 16th century. Both the original and the later deprecating version occurred between the Renaissance, which is probably why the author used it in the first place. Although, I think it is safe to assume that the Duke meant that the “officious” man who had given his Duchess the cherries was a fool because he was eager to help or please the nobility, as if he thought that it would have any effect, which clearly the Duke felt it should not have had. We learn more about just how annoyed he was that his wife did not share his ideological views when he says further on: She thanked men, -- good! but thanked Somehow -- I know not how – as if she ranked My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name With anybody’s gift. (31-34) This is classism at its purest. For the Duke to suggest that the Duchess should have considered his marriage to her a “gift,” more precious than anyone else’s, simply because by doing so she inherited his aristocratic family name, placing her in a higher, more important class, is a perfect indicator at just how deep the Duke has sunk into this false ideology. It’s also a great example of how he constantly commodifies the things in his life. He may call it a “gift,” but he appears to view her marriage to him as more of an exchange than anything else. Or rather, that by giving her this noble family name, he has “purchased” her, she is in a forever debt to him, and he “owns” her. But, because, in his mind, she is apparently not treating the gift at such high sign-exchange value as he expected, and even going so far as to appear as if his exchange value means nothing to her (i.e. not “belonging” exclusively to him), he is incredibly frustrated and angry with her. “Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt, / Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without / Much the same smile?” (43-45) He further reveals that he never brought any of this up to his wife, claiming that: Who’d stoop to blame This sort of trifling? ……………………… To make your will Quite clear to such an one, and say ‘Just this Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss, Or there exceed the mark’ (34-35, 36-39) At first this appears more like a common courtesy towards her. That is, it seems as if his reason for resisting was that it would be rude of him to tell her. However, he later explains that his real reason for doing so was because, even if she had listened to him, she would have had some excellent reason for not meeting his expectations and “-- E’en then would be some stooping; and I choose / Never to stoop.” (4243) He doesn’t care at all about the feelings of his wife! The only thing he’s worried about is making himself look bad by exhibiting a behavior that he feels is very unbecoming of a noble of his “wisdom” and stature. He doesn’t tell her anything, simply because he has planned out the details in his head and realizes there is no “good” result for him. So, what does he do about it instead? “This grew; I gave commands; / Then all smiles stopped together.” (45-46) The unspoken, unanswered question this statement asks is: “What kind of commands could the Duke have given to make certain the Duchess never smiled again?” One of the most common theories that the author, Lois A. Marchino, shares is that he “caused her to be killed.” One unique theory is that he may have “had her shut up in a dungeon or a nunnery, and that she’s as good as dead” (Shmoop Editorial Team). In any case, the statement is chilling, and shows us just how far the Duke was willing to go to protect his “image” in Society. Finally, the Duke reveals who he has been directing this entire monologue to. There is an emissary that has been sent by a Count to discuss the terms of the Duke’s marriage to the Count’s daughter, and how she is to become the Duke’s newest Duchess. The Duke claims that he’s only interested in the Count’s “fair daughter’s self” (52). Yet, because of what we already know about the Duke, we know this is a blatant lie; especially when combined with: “The Count your master’s known munificence / Is ample warrant that no just pretence / Of mine for dowry will be disallowed” (49-51). “Munificent” also derived from Latin in the late 16th century, is defined as “bountiful” or “generous” (“Munificent”). The term, “disallow” means to, “refuse to declare valid” (“Disallow”). Put in context, the Duke is saying that because of the Count’s well-known generousness, he has fair expectations that the Count isn’t going to try to cheat him out of the dowry of his daughter. He’s not interested in marrying her for her “fair self.” He’s marrying her solely for the money. And, we can already see him beginning to commodify his wife soon-to-be as he calls her “[his] object” (53). The poem ends much the way it starts: with him showing off another piece of art in his household to the emissary. This time, it is a bronze statue of Neptune depicted, taming a sea-horse. Again, he places Sign-exchange value upon his collection of art, claiming that, “Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!” (56). Whether his goal is just to further prove to the emissary of his “superior” socioeconomic standing, or also remind the emissary of his “obvious” lower one is unclear. The final two words in the poem stick out the strongest. The poem is called “My Last Duchess,” but it is obvious that the real focus of the poem is the Duke’s personal behavior, and his obsession over commodification, classism, and his own personal gain for both. His whole purpose in life is to constantly increase his socioeconomic standing, and he does so, often at the expense of others. It is not coincidence then that his entire view on the world can be summed up with his final two words of the poem: “for me!” (56). WORKS CITED Browning, Robert, 1812-1889. "My Last Duchess." Wilson Quarterly 23.1 (1999): 109-110. Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 9 July 2013. "Disallow." Oxforddictionaries.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 July 2013. Marchino, Lois A. "My Last Duchess." Masterplots II: Poetry, Revised Edition (2002): 1-3. MagillOnLiterature Plus. Web. 9 July 2013. "Munificent." Oxforddictionaries.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 July 2013. "Officious." Oxforddictionaries.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 July 2013. Shmoop Editorial Team. "My Last Duchess: Section IV (Lines 35-47) Summary" Shmoop.com. Shmoop University, Inc., 11 Nov. 2008. Web. 9 Jul. 2013.