The US Antidumping Law

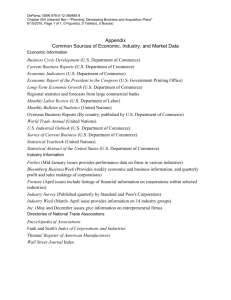

advertisement