More Human Than You: Attributing Humanness to Self and Others

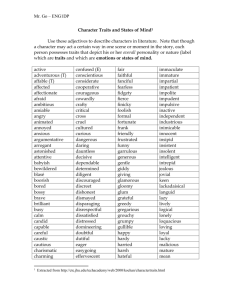

advertisement