Sample Chapter - Canadian Hospitality Law, Liabilities and Risk

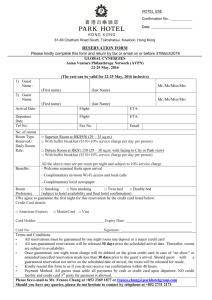

advertisement