The dynamics of qualifications: defining and - Cedefop

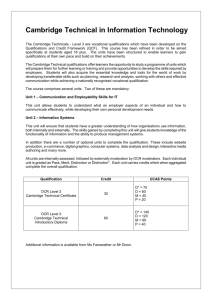

advertisement