Ch. 7: Evaluating and Controlling Technology Quick

advertisement

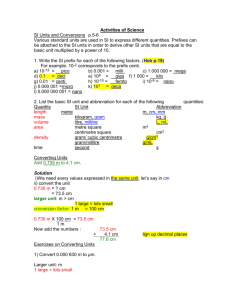

CptS 401—Computers and Society Summer, 2011 Ch. 7: Evaluating and Controlling Technology Quick Reference Guide Description. This quick reference guide summarizes the issues, laws, frameworks, and perspectives discussed in Chapter 7 of the text. Use it as you consider the case studies explored in class, and also as you consider current events, and as you study for the exam. Evaluating Information on the Web (Sec. 7.1.1, pp.351-357) Search engines rank information pages by popularity, not by expert opinion or factual validity. Wikipedia articles can be written by anyone. Democratic journalism is the practice of ranking news articles based on their popularity. This says nothing about their factual accuracy or the trustworthiness. The key question is this: How can we assess the accuracy and trustworthiness of the information we access online? The author suggests "there is no magic formula," but recommends that we "determine who sponsors the site" from which we are getting the information. Another recommendation is to develop a reasonable sense of skepticism. For example, we need to be aware that digital media, especially sound and picture files, can be manipulated in order to deceive us. The ultimate goal is to find sources we trust. Impact of Technology on Writing, Thinking, and Decision-Making (Sec. 7.1.2, pp. 357-360) Computing technologies can be used to replace key human skills of the past, such as spelling, performing arithmetic, and memorizing poems. Some have argued that this is a bad thing, because it leads to "mental laziness" by discouraging "deep thought." As the author points out, "the Web encourages surfing, looking for facts, without evaluation. Reading brief snippets replaces reading books and long articles" (p. 358). A reliance on computers might also release individuals and organizations from taking responsibility for their decisions. Others argue that this is a good thing because it allows humans to focus on honing new skills and becoming more effective and efficient. Evaluating Computer Models (Sec. 7.1.3, pp. 360-367) Computer models are enlisted to model complex phenomena, and ultimately to make predictions that can help guide future decisions. Examples include models of climate change, natural resource consumption, life cycle analysis of cloth vs. disposable diapers, and economic conditions relative to tax rates. Computer models are necessarily simplifications of the real thing. They make assumptions and gloss over details that are deemed to be inconsequential. Computer models vary widely in their accuracy. The following considerations are relevant (p. 362): o How well is the underlying theory or science understood? o Are the assumptions and simplifications used by the model reasonable? o How closely to the model's predictions correspond with measurements taken in the real world? Impact of Technology on Communities (Sec. 7.2, pp. 367-372) Much social interaction has shifted online. Critics fear that we are losing the vibrancy of our local communities, and that we are becoming socially isolated. One measure of the vibrancy of local communities is the extent to which we join clubs and social organizations. Memberships in clubs and social organizations is declining, but it is unclear what the cause is. Studies that have attempted to correlate internet usage with social participation have been inconclusive. Electronic commerce gives consumers another choice besides local stores. This leads to increased competition; the local stores get less business and may no longer be able to survive. According to the author, this kind of change "creates new options and causes some old options to disappear. Those who prefer a new option see it as progress. Those who prefer a lost option view the change as bad. Neither side's preference is inherently or absolutely better than the other" (p. 371, gray box). 1 Digital Divide (Sec. 7.3, pp. 372-375) The digital divide refers to differences among different groups' access to computers and the internet. The underlying goal is to ensure equal access to all. Initially, efforts to bridge the digital divide focused on helping the poor and those in rural areas gain access to computers and the internet. Later on, efforts focused on helping those in poor countries gain access to computers and the internet. The digital divide is not a new phenomenon. Similar divides existed with respect to earlier technologies, such as telephones and telephones. Luddite Critique of Computer Technology (Sec. 7.4.1, pp. 376-382) Luddite is a term used to refer to people who oppose technological progress. It was coined in the early 19th century by people who opposed the development of factories and mills. Modern luddites call themselves “neo-Luddites.” Neo-Luddites tend to focus on the problems created by technology, without examining solutions or tradeoffs. Some critiques include that computers o cause massive unemployment o manufacture needs that weren’t there before (don’t address real problems) o cause social inequity o cause social isolation and impair development of social and intellectual skills o destroy the environment and disconnect people from nature The Luddite critique of technology is shaped by a world view that "makes the moral judgment that making money and producing things is pernicious," and that places a high priority "on not disturbing nature" (p. 379). The book author offers a harsh critique of the Luddite position: "The argument that capitalists or technologies manipulate people to buy things they don't really want, like the argument that use of computers has an insidiously corrupting effect on computers users, displays a low viwe of the judgment and autonomy of ordinary people" (p. 381). Benefits of Computer Technology (Sec. 7.4.2, pp. 382-385) By many economic and health measures, we are better off now than we were a century ago. For example, food prices are down, natural resource prices are down, disease is down, and life expectancy is up. Technology isn't the only contributing factor, but it is one of them. Luddites argue that computer technology benefits mainly governments and large corporations. In contrast, others see technology has benefiting the poorest, weakest people in society: "The standard of living of commoners is higher today than that of royalty only two centuries ago—especially their life and life expectancy" (Economist Julian Simon, as quoted on p. 384). Deciding on Whether to Use Technology (Sec. 7.5.1, p. 386) While most people may accept the view that people can choose whether or not to use technology, critics argue that technology isn't neutral: "Once a technology is admitted [to our culture], it plays out its hand; it does what it is designed to do" (Neil Postman quoted on p. 386). These critics believe that technology is really in control, or that big corporations or governments are making decisions without consulting ordinary people. The Difficulty of Prediction (Sec. 7.5.2, pp. 387-390) Luddite Postman asserts that "technology does what it is designed to do" (p. 387). However, numerous examples throughout history illustrate how difficult it is to predict the impact of technology on society. Computer scientist Peter Denning believes "people adopt technologies that give them more choices," while humancomputer interaction specialist Don Norman acknowledges society's role in influencing technology uses when he states that "the failure to predict the computer revolution was the failure to undersatnd how society would modifyt he original notion of a computational device into a useful tool for everyday activities" (p. 388). 2 Computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum's inaccurate predictions in 1975 regarding the value of speech recognition technology are used in the book to illustrate the difficulties of predicting technology. Intelligent Machines (Sec. 7.5.3, pp. 391-393) Can computer parts be implanted into humans to replace damaged human parts, or to enhance human functioning? Will there ever be intelligent robots that rival humans? There is much debate among technologists on these issues and their ethical implications. Technological singularity is that point at which artificial intelligence advances so far that we can no longer understand what lies ahead. whether and when intelligent machines that rival humans will be developed. Some technologists believe that the human race will be transformed into "superintelligent, genetically engineered creatures" (p. 391) in the near future. o In support of this outlook is Moore's Law, which states that the power of computer microcomputers doubles every 18 to 24 months. This suggests that by 2030, computer processing power will equal that of the human brain. o In contrast, there are reasons this outlook may not come to fruition. The progress of computational power may slow down. Even it remains at its current pace, it's not clear that software could be developed to emulate human intelligence. It's a very difficult problem, and to date there has been little success in building systems that are truly intelligent in the general sense humans are. While super-intelligent systems may be far off in the horizon, it is prudent to anticipate potential problems of superintelligent systems and computer-enhanced humans, so that we can design appropriate responses and protections. Some believe we need treaties akin to nuclear non-proliferation treaties in order to limit the development of technologies that could eventually take over the world. However, it is difficult to know where to draw the line between the development of technologies that benefit society and the development of technologies that could potentially lead to its demise. 3