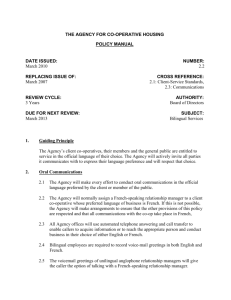

Status of Co-operatives in Canada

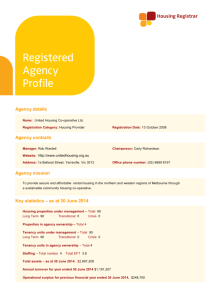

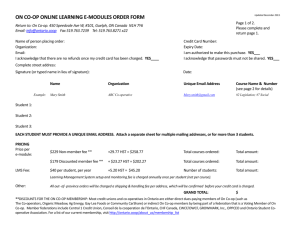

advertisement