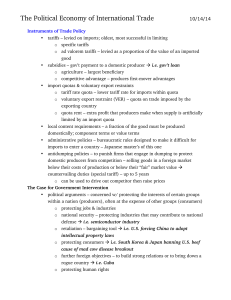

The role of business organization in international integration

advertisement