Communication Disorders Handbook - Education

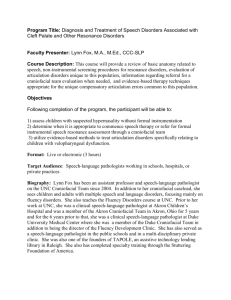

advertisement