Siegler Chapter 10: Emotional Development

advertisement

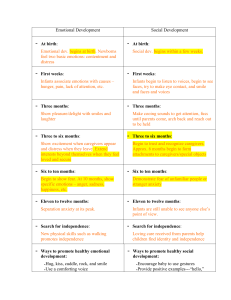

11/5/2015 Emotional Development How Children Develop Chapter 10 Emotional Intelligence A set of abilities that contribute to competent social functioning: Being able to motivate oneself and persist in the face of frustration Control impulses and delay gratification Identify and understand one’s own and others’ feelings Regulate one’s moods Regulate the expression of emotion in social interactions Empathize with others’ emotions 1 11/5/2015 Emotional Intelligence EQ is a better predictor than IQ of how well people will do in life, especially in their social lives Emotion Characterized by neural and physiological responses, subjective feelings, cognitions related to those feelings, and the desire to take actions Most psychologists share this general view: but they disagree on importance of its key components 2 11/5/2015 Perspectives Discrete Emotions Theory The Functionalist Approach Research supports both perspectives to some degree, and no one theory has emerged as definitive. Discrete Emotions Theory Argues that: Emotions are innate and are discrete from one another from very early in life Each emotion is packaged with a specific and distinctive set of bodily and facial reactions 3 11/5/2015 The Functionalist Approach Maintains that emotions are not discrete from one another and vary somewhat based on the social environment Emphasizes the role of the environment in emotional development Proposes that the basic function of emotions is to promote action toward achieving a goal Characteristics of Some Families of Emotions 4 11/5/2015 Happiness Smiling is the first clear sign of happiness that infants express Young infants smile from their earliest days, but the meaning of their smiles appears to change with age Social Smiles are directed toward people and first emerge as early as 6 to 7 weeks of age Happiness Around 3 or 4 months, infants laugh as well as smile during activities At about 7 months, infants start to smile primarily at familiar people, rather than at people in general In 2nd year, children clown around and enjoy making others laugh * 5 11/5/2015 Negative Emotions The first negative emotion that is discernible in infants is generalized distress By 2 months, facial expressions of anger or sadness can be differentiated from distress/pain in some contexts By the second year of life, this differentiation is no longer difficult Negative Emotions Also display anger when: stimulation removed caregiver leaves arms restrained Why? 6 11/5/2015 Anger Fear The first clear signs of fear emerge at around 6 or 7 months, when unfamiliar people no longer provide comfort and pleasure similar to that provided by familiar people The fear of strangers intensifies and lasts until about age 2; but there is variability 7 11/5/2015 Evidence of Fear in Young Children Separation Anxiety Refers to feelings of distress that children, especially infants and toddlers, experience when they are separated, or expect to be separated, from individuals to whom they are attached It is a salient and important type of fear and distress that tends to increase from 8 to 13 or 15 months and then begins to decline This pattern is observed across many cultures 8 11/5/2015 Separation Anxiety Self-Conscious Emotions Feelings such as guilt, shame, embarrassment, and pride that relate to our sense of self and our consciousness of others’ reactions to us Emerge during the second year of life Around 15 to 24 months, children show embarrassment when the center of attention By 3 years, children’s pride is increasingly tied to their level of performance 9 11/5/2015 Guilt and Shame Guilt is associated with empathy for others and involves feelings of remorse and regret and the desire to make amends Shame does not seem to be related to concern about others Whether children experience guilt or shame partly depends on parental practices Emotions in Middle Childhood From early to middle childhood: acceptance by peers and achieving goals are important sources of happiness and pride By the early school years, children’s perceptions of others’ motives and intentions are important in determining whether or not they will be angered Children overall become less intense and less emotionally negative with age in the preschool and early school years 10 11/5/2015 Emotions in Adolescence Adolescence is a time of greater negative emotion than middle childhood A minority experience a major increase in the occurrence of negative emotions, often in their relations with their parents Depression The rate of clinical depression, which is 3% prior to adolescence, is 15% or higher from age 15-18... An addition 11% of U.S. youth experience less serious symptoms of depression Hispanic children report more symptoms of depressions than do Euro- or African Americans Children with depression frequently exhibit behavior problems 11 11/5/2015 Depression Depression Possible causes of depression include genetic factors, maladaptive belief symptoms, feelings of powerlessness, negative beliefs and self-perceptions, and the lack of social skills Family factors also contribute to depression Antidepressant drugs are most common treatment 12 11/5/2015 Regulation of Emotion The Development of Emotional Regulation The Relation of Emotional Regulation to Social Competence and Adjustment Patterns in Developing Self-Regulation Transition from Regulation by Others to Self-Regulation Use of Cognitive Strategies to Control Negative Emotions Ability to Select Strategies Appropriate for the Situation 13 11/5/2015 Emotional Self-Regulation The process of initiating, inhibiting, or modulating internal feeling states, emotion-related physiological processes, and emotion-related cognitions or behaviors in the service of accomplishing one’s goals Its emergence in childhood is a long, slow process Transition to Self-Regulation In the first months of life, parents help infants regulate their emotional arousal by controlling their exposure to stimulating events 6 months: infants reduce distress by averting gaze and self-soothing Between 1 and 2 year: infants increasingly divert their attention to non-distressing objects or people 14 11/5/2015 Transition to Self-Regulation Over the course of the early years, children become more likely to rely on themselves rather than their parents Children’s improving self-regulation is due at least in part to the increasing maturation of the neurological system They are also influenced by increases in adults’ expectations of children and to age-related improvement in the ability to inhibit motor behavior Individual Differences in Emotion and its Regulation Temperament 15 11/5/2015 Temperament The constitutionally based individual differences in emotional, motor, and attentional reactivity and selfregulation that demonstrate consistency across situations, as well as relative stability over time Differences in the various aspects of children’s emotional reactivity that emerge early in life are labeled as dimensions of temperament New York Longitudinal Study by Thomas and Chess 141 children followed from infancy to adulthood) Infants were rated on 9 personality dimensions: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Activity level Rhythmicity Approach/withdrawal Adaptability Emotional reactivity Responsiveness to stimuli Mood (positive or negative) Distractibility Attention span 16 11/5/2015 Infant Temperament Easy 40% Regular routines, cheerful, adapts easily Difficult 10% Irregular routines, dislikes new experiences, reacts negatively Slow-towarm up 15% Inactive, mid to low-key reactions, negative in mood, adapts slowly. 35% fit no category: a mixture of these. Difficult pattern: 70% developed behavior problems by school age (only 18% of easy children did). Slow-to-warm-up: few problems in early years, but some later in school when need to respond actively/quickly. 17 11/5/2015 Infant Temperament In contrast to Thomas and Chess’s approach, many contemporary psychologists believe that it is important to Assess positive and negative emotion as separate components of temperament Differentiate among types of negative emotionality Assess different types of regulatory capacity Recent research suggests that infant temperament is captured by six dimensions Fearful distress, irritable distress, attention span and persistence, activity level, positive affect, and rhythmicity Examples of Items in Mary Rothbart’s Temperament Scales 18 11/5/2015 Examples of Items in Mary Rothbart’s Temperament Scales The Stability of Temperament Children who as infants showed behavioral inhibition with novel stimuli also showed elevated levels of fear in novel situations at age 2 and elevated levels of social inhibition at age 4 ½ It is important to note, however, that some aspects of temperament tend to be more stable than others * 19 11/5/2015 Temperament and Social Adjustment Different problems with adjustment are associated with different temperaments Children’s adjustment depends on how their temperament fits with the demands and expectations of the social environment: a concept described as goodness of fit Moreover, the child’s temperament and the parents’ socialization efforts seem to affect each other over time Children’s Emotional Development in the Family Quality of the Child’s Relationships with Parents Parental Socialization of Emotional Responding 20 11/5/2015 Personality Refers to the pattern of behavioral and emotional propensities, beliefs and interests, and intellectual capacities that characterize an individual Has its roots in temperament but is shaped by interactions with the social and physical world Socialization How individuals, through others, develop the skills and ways of thinking and feeling, as well as standards and values, that allow them to adapt to their group and live with other people Parents, teachers, and other adults are important socializers for children, (other children, the media, and social institutions too) 21 11/5/2015 Parental Emotions The emotions to which children are exposed may affect their level of distress and arousal The consistent and open expression of positive emotion in the home is associated with positive outcomes When negative emotions are predominant, children have low levels of social competence and to express negative emotions themselves Parental Reactions to Emotion Parents who respond to their children’s sadness and anxiety by dismissing or criticizing their feelings communicate to their children that their feelings are not valid In turn, their children tend to be less emotionally and socially competent than children whose parents are emotionally supportive 22 11/5/2015 Children’s Understanding of Emotion Identifying the Emotions of Others Understanding the Causes of Emotion Children’s Understanding of Real and False Emotions Understanding Simultaneous and Ambivalent Emotions Identifying the Emotions of Others The first step in the development of emotional knowledge is the recognition of different emotions in others By 4 to 7 months, infants can distinguish certain emotional expressions, such as happiness and surprise At 8 to 12 months, children demonstrate social referencing, the use of a parent’s facial, gestural, or vocal cues to decide how to deal with novel, ambiguous, or possibly threatening situations By age 3, children in laboratory studies demonstrate a rudimentary ability to label a fairly narrow range of emotional expression 23 11/5/2015 Identifying the Emotions of Others Young children are best at labeling happiness, with the ability to distinguish among different negative emotions gradually appearing the late preschool and early school years Most children cannot label more complex emotions until early- to mid-elementary school The ability to discriminate and label different emotions helps children respond appropriately to their own and others’ emotions 24