Market segmentation by using consumer lifestyle

advertisement

European

Journal of

Marketing

33,5/6

470

Market segmentation by using

consumer lifestyle dimensions

and ethnocentrism

An empirical study

I^et-eived N4arch 1997

Revised December 1997

Orsay Kucukemiroglu

College of Business Administration, Pennsylvania State University,

York, Pennsylvania, USA

Keywords Consumer behaviour, Consumer marketing. Country of origin. Lifestyles,

Market segmentation, Turkey

Abstract Identifies consumer market segments existing among Turkish consumers by using

lifestyle patterns and ethnocenUism. Data for the study were collected through personal intervieivs

in ktanbuL Survey findings indicate tliat there are several lifestyle dimensions apparent among

the Turkish cottsumers which liad an influence on their ethnocentric tendencies. Nonethnocentric

Turkish consumers tend to have significantly more favorable beliefs, attitudes, and intentions

regarding imported products than do ethnocentric Turkish consumers. Using the lifestyle

dimensions extracted, three distinct market segments were found Consumers in ttie Liberals/

trend setters customer market segment showed similar behavioral tendencies and purchasing

pattents to consumers in western countries. Thejindings provide some implications to marketers

who currently operate in or are planning to enter into Turkish markets in the near future.

Introduction

_

Vol. 33 No. S/6, 1993, pp. 4704«7

Over the last two decades, global trade has changed substantially both in

magnitude and orientation. This rapid transformation has, in most cases,

created enormous mai'ket opportunities for countries and industries around the

globe. It is expected that this trend will continue and expose consumers to a

wider range of foreign products than ever before. Consequently, increased

globalization of today's business environment has also led to a renewed interest

in the effect of a product's country of origin on consumer decision making

{Papadopoulos and Heslop, 1993).

Country-of-origin is a concept which states that people attach a stereotypical

"made in" perception to products from specific countries and this influences

purchase and consumption behaviors in multi-national markets. In addition,

the concept encompasses perceptions of a sourcing country's economic,

political, and cultural characteristics, as well as specific product image

perceptions {Parameswaran and Pisharodi, 1994). Consumer behavior and

international marketing literature have extensively documented the impact

that a consumer's knowledge about a product's country of origin has on

subsequent product evaluations (Bilkey and Nes, 1982; Han, 1990; johanson et

al, 1985; Cordell, 1992; Hong and Wyer, 1989; Thorelli et al., 1988; Wang and

Lamb, 1983; Tse and Gom, 1993; Papadopoulos et ai, 1990). Bilkey and Ness

/moov

i

J ..I. ..

l

^

j ^

L

^-

•

l

.

i

•• MCBUnivtrsity [Tea, u309-(B66 (190^;) noted t h a t people tend to h a v e c o m m o n notions c o n c e m m g p r o d u c t s a n d

peoples of other countries, and also that these stereotyping evaluations carry

over into the product evaluations. They found that overall evaluations of the

product are almost always influenced by country stereotyping. It is also

evident that customers' attitudes toward imports can vary significantly from

one country to another (Morello, 1984; Cattin et al, 1982). Stereotypes are

perceived differently by consumers across national boundaries as well, because

consumers share similar values and belief structure in their evaluations of

"made in" labels (Yavas and Alpay, 1986; Tongberg. 1972).

Research has also shown that nationalistic, patriotic and ethnocentric

sentiments can affect the evaluation and selection of imported products.

Consumer nationalism or patriotism, a construct that emerged from the country

of origin literature in the 1980s, asserts that patriotic emotions affect attitudes

about products and purchase intentions. Consumers from a wide range of

countries have been found to evaluate their own domestic products more

favorably than they do foreign ones (Han, 1988; Baumgartner and Jolibert,

1977; Bannister and Saunders, 1978; Darling and Kraft, 1977; Papadopoulos et

aL, 1990; Dickerson. 1982; Nagashima, 1970; Reierson, 1966; Narayana, 1981;

Johansson et al,, 1985).

Along with increased nationalism and heavy emphasis on cultural and

ethnic identity, consumer ethnocentrism will be a potent force in the global

business environment in the years to come. Hence, understanding whether the

level of ethnocentrism is differentiating customer characteristics for products

originating from overseas is useful for the development of marketing strategies

for imported products. Keeping this in mind, the objective of this paper is to

examine the process underlying consumers' attitudes toward products being

imported into their domestic markets. With consumer ethnocentrism as the

focal construct, this study uses lifestyle analysis as a proxy for ethnocentric

tendencies, along with other research techniques, to identify homogeneous

consumer market segments sharing similar patterns of social norms, beliefs,

and behaviors among Turkish consumers. Once these market segments are

identified, appropriate marketing strategies and policies can be developed to

reach them. The findings of the study offer managerial and public policy

implications which may facilitate the development of better consumer markets

in developing economies such as Turkey.

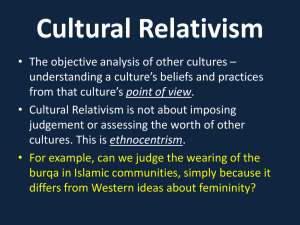

Consumer ethnocentrism and lifestyle

A general definition of consumer ethnocentrism refers to the phenomenon of

consumer preference for domestic products, or prejudice against imports

(LeVine and Campbell, 1972). Consumer ethnocentrism represents the beliefs

held by consumers about the appropriateness, indeed morality, of purchasing

foreign-made products (Shimp and Sharma, 1987). Ethnocentrism may be

interpreted as that purchasing imports is wrong, not only because it is

unpatriotic, but also because it is detrimental to the economy and results in loss

of jobs in industries threatened by imports. A series of nomological validity

tests conducted in the USA by Shimp and Sharma (1987) indicated that

Lifestyle

dimensions and

ethnocentrism

471

European

Journal of

Marketing

33,5/6

472

consumer ethnocentrism is moderately predictive of consumers' beliefs,

attitudes, purchase intentions, and purchases. They also show that

ethnocentric tendencies are significantly negatively correlated with attitudes

towards foreign products and purchase intentions. Consumer patriotism or

ethnocentrism proposes that nationalistic emotions affect attitudes about

products and purchase intentions. In particular, consumer nationalism

influences cognitive evaluations of the products and consequently affects

purchase intent. This implies that nationalistic individuals will tend to perceive

the quality of domestic products as higher than that of foreign products (Han,

1989). According to Sharma et al, {1992), ethnocentric tendencies among

Korean consumers play a more important role in decision making when the

product of interest is an important source of jobs and income for the domestic

economy. When the imported product is perceived as less necessary,

ethnocentric tendencies may play a more important role in decision making.

The sti'ength, intensity and magnitude of consumer-ethnocentrism do vary

from culture/country to culture/country. Some authors argue that

ethnocentrism is a part of human nature (Mihalyi, 1984; Rushton. 1989; Herche,

1992).

Over the years, a number of studies have been carried out to understand the

behavior of the ethnocentric consumer better (tXirvasula and Netemeyer, 1992;

McLain and Stemquist, 1991; Shimp and Sharma, 1987; Sharma et al, 1992;

Netemeyer et al, 1991; Han, 1988; Chasin et al, 1988; Kaynak and Kara, 1996a).

Among these, an important contribution to consumer research has been the

development and limited international application of the CETSCALE, which is

designed to measure consumers' ethnocentric tendencies related to purchasing

foreign versus American products. It consists of 17 items scored on seven-point

Likert-type formats and represents an accepted means of measuring consumer

ethnocentrism aaoss cultures/nations. In their study, Shimp and Sharma

(1987) suggested several potential applications of the scale to population

groups in countries dissimilar to the USA. However, researchers were first

cautioned to provide an accurate translation and assessment of the scale's

psychometric properties. Further study conducted by Netemeyer et al (1991)

showed strong support for the psychometric properties and nomological

validity of the scale aaoss four different countries, France, Germany, Japan

and the USA. They reported alpha levels ranging from 0.91 to 0.95 across the

four countries studied. A strong support for the CETSCALE's

unidimensionality and internal consistency was established. However, little

research exists which empirically addresses biases encountered in conducting

consumer ethnocentrism research (Albaum and Peterson, 1984). Netemeyer et

al (1991) and Kaynak and Kara (1996a) strongly recommended that researchers

translate the CETSCALE into other languages and use it in other countries and

regions.

The success of a marketing model inherently lies in researchers' ability to

come up with variables that really distinguish people's performance in the

marketplace. This becomes even more important in a foreign market

environment. It is known that these variables are far more than just

demographic and socioeconomic characteristics (Westfall, 1962). Demographic

dimensions have received broader acceptance and lend themselves easily to

quantification and easy consumer classification. However, the usage of

demographics, for instance, has been questioned and argued that demographic

profiles have not been deemed sufficient because demographics lack richness

and often need to be supplemented with additional data (Wells, 1975). Social

class adds more depth to demographics, but it, too, often needs to be

supplemented in order to obtain meaningful insights into audience

characteristics. "Lifestyle segmentation" has been a useful concept for

marketing and advertising planning purposes (Wells and Tigert, 1977; Kaynak

and Kara, 1996b). Lifestyle, of course, has been defined simply as "how one

lives". In marketing, "lifestyle", however, describes the behavior of individuals,

a small group of interacting people, and large groups of people (e.g. market

segments) acting as potential consumers. Thus, the concept of the lifestyle

represents a set of ideas quite distinct from that of personality. The lifestyle

relates to the economic level at which people live, how they spend their money,

and how they allocate their time (Anderson and Golden, 1984). Lifestyle

segmentation research measures people's activities in terms of:

• how they spend their time;

• what interests they have and what importance they place on their

immediate surroundings;

• their views of themselves and the world around them; and

• some basic demographic characteristics.

The most widely used approach to lifestyle measurements has been activities,

interests, and opinions (AlO) rating statements (Wells and Tigert, 1977). The

focus of marketers and consumer researchers has generally been on identifying

the broad trends that influence how consumers live, work, and play. It allows a

population to be viewed as distinct individuals with feeling and tendencies,

addressed in compatible groups (segments) to make more efficient use of mass

media. In general, researchers tend to equate psychographic with the study of

lifestyles. Psychographic research is used by market researchers to describe a

consumer segment so as to help an organization better reach and understand

its customers. Hence, lifestyle patterns provide broader, more threedimensional views of consumers so that marketers can think about them more

intelligently. The basic premise of lifestyle research is that the more marketers

know and understand about their customers, the more effectively they can

communicate with and serve them (Kaynak and Kara, 1996b). However, a

majority of lifestyle studies have been carried out in the westem countries. Life

style information in Turkey is surely lacking. This study uses lifestyle

analysis, along with other research techniques, to identify consumer market

segments sharing similar patterns of social beliefs and behaviors, using

Lifestyle

dimensions and

ethnocentrism

473

European

Joumal of

Marketing

33.5/6

474

Turkish consumers. Once these market segments are identified, appropriate

marketing strategies and policies can be developed to reach them.

Methodology

The data for this study were collected through self-administered questionnaires

from Istanbul, Turkey during the winter of 1995. In Istanbul, the largest and

the most cosmopolitan city in Turkey, a sizable percentage of the population

make their living from service, light manufacturing, and resource-based

industries. Choice of this particular city was made for the belief that the people

who lived in the big city are more habituated to questionnaires, and would

respond, which had an impact on selection decision. Furthermore, every effort

was made to get a cross-section of the population by selecting nine different

parts of Istanbul for the administration of this survey - Aksaray, Bakirkoy,

Besiktas, Beyazit, Fatih, Kadikoy, Karakoy, and Taksim, where shopping

centers are located and population density is high, were studied. Respondents

were randomly intercepted in the streets and contacted personally with the help

of senior students from local higher education institutions. A total of 532 usable

questionnaires were completed

A questionnaire for the study was developed in English first then translated

into Turkish by a bilingual associate. Back translation was also done to check

any inconsistency as well as possible translation errors. Before the survey

administration, pre-test of the questionnaire with a small group of respondents

was conducted, and the results were satisfactory. The questionnaire consisted

of five sections. In the first section, 56 activities, interest and opinions (AIO)

statements obtained from marketing literature were used to identify lifestyles

of Turkish consumers (Wells, 1975; Wells and Tigert, 1977; Mitchell, 1983;

Anderson and Golden, 1984). A five-point Likert scale was used, "1" being

"strongly disagreeing" and "5" being "strongly agree". The second section of

the questionnaire contained questions regarding the household decisionmaking process. The types of questions used in the instrument were very

similar to those incorporated by Davis and Rigaux (1974). Each respondent was

instructed to indicate the primary decision maker in the family (husband, wife

or the husband and wife jointly):

•

•

•

'

when they bought;

where they bought;

what they bought; and

how much they paid for the purchases of seven products and services:

grocery, major appliances, furniture, automobiles, savings, vacations,

and life insurance.

The third section of the questionnaire included questions about ethnocentrism.

C/)nsumer ethnocentrism was measured by the popular CETSCALE developed

by Slump and Sharma (1987). In the fourth section of the questionnaire, using a

five-point Likert scale, perceptions of foreign countries' products were

measured. The last section of the questionnaire included demographic and

socioeconomic questions, which are used to interpret the responses on other

questions.

Lifestyle

dimensions and

ethnocentrism

Analysis and discussions

Table I shows the demogi-aphic and socioeconomic questions which were used

to interpret the responses on other questions. Past literature indicated that

ethnocentric consumers had different lifestyle patterns than non-ethnocentric

consumers (LaTour and Henthome, 1990). The reliability analysis of the 56

activities, AIO statements produced a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.923,

which can be considered satisfactory. In order to understand the existing

lifestyle dimensions of the Turkish consumers and discern what kind of

lifestyle characteristics these consumers possessed, AIO statements were

factor analyzed. The resultant factor matrix was rotated using Varimax

rotations. The results of the factor analysis ai"e given in Table II.

The analysis produced eight factors, which explained 68.55 percent of the

total variance. Only those factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1.00 were

retained. The first factor consists of "I usually have one or more outfits that are

of the very latest style (0.713)", "When I must choose between the two, I usually

Chai-acteristics

Age

Below 20

20-30

31-40

41-50

Over 50

Income^

< 10,000.000

11-20.000.000

21-30,000.000

31-40,000.000

> 40,000,000

Marital, status

Single

Married

Gender

Male

Female

Education

Less than high school

High school

Some college

College

Note: ^ Monthly income in Turkish currency (US$1 = 60,000 Turkish Lira)

475

Frequencies

37

188

126

93

78

64

153

189

81

43

109

423

215

317

%

212

117

138

Table L

Demographic and

socio-economic

characteristics of

respondents

European

Joumal of

Marketing

33,5/6

476

u.

eg - ^ 00

CO ^

I—

_ O m

Q

t".. t-- to ©

O O O O

I-H

Table n .

Rotated factor pattem

(Varimax)

gj

N

111= ^

Lifestyle

dimensions and

ethnocentrism

I

477

I ^ !=;

3

^

-.1

O

3

O

3 c "6

to

«3

O

C^J C M

t ^

•—I

o o

o

o

35

o

^5

CO

to

o

IO

.—1

CM

to

o

Table H.

European

Joumal of

Marketing

33,5/6

1

•u

478

3

Table H.

ui

Ol

o

o

Lifestyle

dimensions and

ethnocentrism

^

rf

C-f^

CO

.—I

tn

in

00

--i

•—I

CO

C^

^^

^^

u5

to

in

479

CM

o

o

CO

in

CM CM

I

CJ

Table O.

European

Journal of

Marketing

33,5/6

480

dress for fashion, not for comfort (0.676)", "An important part of my life and

activities is dressing smartly (0.660)", "I often try the latest hairdo styles when

they change (0.564)", "I like parties where there is lots of music and talk

(0.578)", "I would rather spend a quiet evening at home than go out to a party

(-0.502)", "I am a housebody (-0.574)". "I often try new stores before my friends

and neighbors do (.4902)", "I spend a lot of time talking with my friends about

products and brands (0.3363)", "I like to watch or listen to football or basketball

games (0.2283)". This factor accounts for 13.21 percent of the total variance and

may be labeled as Fashion consciousness factor. The second factor explains

11.72 per cent of the variance and consists of "I think I have more selfconfidence than most people (0.764)", "I am more independent than most people

(0.703)", "I think I have a lot of personal ability (0.694)", "I like to be considered

as a leader (0.601)", "My friends or neighbors often come to me for advice

(0.564)", "I sometimes influence what my friends buy (0.532)", "I would like to

take a trip around the world (0.502)", "I'd like to spend a year in a foreign

country (0.4377)", "People come to me more often than I go them for

information about brands (0.3415)", "I often seek out the advice of my friends

regarding which brand to buy (-0.2712)". This factor may be labeled as

Leadership factor. The third factor delineates a cluster of relationships among

"When my children are ill in bed, I drop most everything else in order to see to

their comfort (0.767)", "My children are the most important things in my life

(0.736)", "I try to arrange my home for my children's convenience (0.680)", "I

take a lot of time and effort to teach my children good habits (0.621)", "I usually

watch the advertisements for announcements of sales (0.4145)", "I will

probably have more money to spend next year than I have now (0.3872", "Five

years from now the family income will probably be a lot higher than it is now

(0.2993)", "I like to sew and frequently do (0.2415)", "I often make my own or

my children's clothes (0.2213)". This factor explains 10.47 percent of the

variance and may be labeled as Family concern factor. The fourth factor loaded

on "During the warm weather I drink low calorie soft drinks several times a

week (0.654)", "I buy more low calorie foods than the average housewife

(0.605)", "I use diet foods at least one meal a day (0.524)", and "I participate in

sport activities regularly (0.585)". This factor explains 9.18 percent of the

variance and may be labeled as Health consciousness factor. The fifth factor

accounts for 7.42 percent of the variance. It consists of "I must admit I really do

not like household chores (0.765)", "I find cleaning my house an unpleasant

task (0.727)", "My idea of housekeeping is once over lightly (0.603)", "I usually

keep my house very neat and clean (-0.578)", "I am uncomfortable when my

house is not completely clean (-0.541)", and "I enjoy most forms of homework

(-0.501)", "I don't like to see children's toys lying around (-^.4827)", "I like to

pay cash for everything I buy (0.2914)". This factor may be labeled as Carefree

factor. The sixth factor consists of "I am an active member of more than one

service organization (0.671)", "I do volunteer work for a hospital or service

organization on a fairly regular basis (0.645)", "I like to work on community

projects (0.541)", and "I have personally worked in a political campaign or for a

candidate or an issue (0.512)". This factor accounts for 6.88 percent of the total

variance and may be labeled as Community consciousness factor. The seventh

factor consists of "I shop for specials (0.749)", "I find myself checking the prices

in the grocery store even for small items (0.655)," "I usually watch the

advertisements for announcements of sales (0.618)", "A person can save a lot of

money by shopping around for bargains (0.531)", "You can save a lot of money

by making your own clothes (0.3432)". This factor may be labeled as Cost

consciousness factor and explains 5.71 percent of the variance. The eighth

factor includes "I depend on canned food for at least one meal a day (0.645)", "I

couldn't get along without canned foods (0.630)", "Things just do not taste right

if they come out of a can (-0.512)", "It is good to have credit cards (0.4349)", "I

would like to know how to sew like an expert (-0.3714)", "I would rather go to a

sporting event than a dance (0.2832)". This factor accounts for 3.96 percent of

the variance and may be labeled as Practicality Factor.

To measure convsumer ethnocentrism the 17-item CETSCALE developed by

Shimp and Sharma (1987) was used. Table III shows the result of the reliability

analysis of these 17 items.

Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.886 can be considered a reasonably high

reliability coefficient. Based on this, it can be assumed that all 17 items used are

Item

Turkish people should always by Turkish-made products instead of imports

Only those products that are unavailable in Turkey should be imported

Buy Turkish made products. Keep Turkey working

"

Turkish products, first, last, and foremost

Purchasing foreign made products is un-Turkish

It is not right to purchase foreign products, becau^ it puts Turks out of jobs

A real Turk should always buy Turkish-made products

We should purchase products manufectured in Turkey instead of letting other

countries get rich off us

It is always best to purchase Turkish products

There should be very little trading or purchasing of goods from other countries

unless out of necessity

Turks should not buy foreign products, because this hurts Turkish business

and causes unemployment

Curbs should be put on all imports

It may cost me in the long-run but I prefer to support Turkish products

Foreigners should not be allowed to put their products on our markets

Foreign products should be taxed heavily to reduce their entry into Turkey

We should buy from foreign countries only those products that we cannot

obtain within our own country

Turkish consumers who purchase products made in other countries are

responsible for putting their fellow Turks out of work

Lifestyle

dimensions and

ethnocentrism

481

Reliability*^

0.879

0.879

0.878

0.876

0.877

0.870

0.874

0.878

0.884

0.880

0.884

0.874

0.880

0.885

0.881

0.884

0.883

Notes:

'^ Response format is a seven-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree = 7, strongly disagree =

'' Calculated using Cronbach alpha (alpha if item deleted). Overall alpha = 0.886

Table III.

17-item CETSCALK^

European

Journal of

Marketing

33,5/6

482

measuring the same construct (ethnocentrism) and, therefore, a summative

measure can be used to represent the ethnocentrism score of the respondents.

To understand the underlying relationship between the factors (life style

dimensions) extracted by the factor analysis and the ethnocentrism score,

Pearson product moment correlation coefficients were computed. The results

are shown in Table FV.

The analysis of the results reveals that fashion consciousness and leadership

factors have statistically significant inverse relationships with the

ethnocentrism score. In other words, less ethnocenti-ic Turkish consumers are

more fashion conscious and leadership oriented or vice versa. On the other

hand, family concern factor and community consciousness factor liave

statistically significant positive correlation, with the ethnocentrism score. This

means those Turkish consumers more family concerned and the community

conscious are more ethnocentric. The correlations between the rest of the

factors and the ethnocentrism score were statistically insignificant.

Further analysis included cluster analysis on the 56 AIO statements. The

objective was to identify consumer market segments existing in Turkey by

using lifestyle analysis. It would be rather useful to identify the lifestyle

variables that make some Turkish consumers ethnocentric and the variables

that influence the others to change. The number of clusters were identified by

using pseudo F-ratio, cubic clustering criteria and standard deviation within

clusters criteria (Milligan and Cooper, 1985). As a result, three distinct clusters

were identified (see Table V).

Ethnocentrism

score

Lifestyle dimensions

Table IV.

Peai"son correlation

coefficient-s between

lifestyle dimensions

and ethnocentrism

score

Note: ' Significant at a < 0.01

Number of clusters

Table V.

Comparison of clusters

by different criteria

-0.327'

-0.251'

0.383'

0.081

-0.073

0.311'

0.033'

-0.029

Fashion conscious factor

Leadership factor

Family concern factor

Health consciousness factor

Care-free factor

Community consciousness factor

Cost consciousness factor

Practicality factor

2

3

4

Pseudo F-ratio

Cubic clustering

CTiteria

Standard deviation

within clusters

17.62

16.02

11.58

30.917

28.025

23.833

1.201

0.937

0.878

Then, clusters were defined using ethnocentrism, household decision making,

product attribute importance, demographic and socio-economic characteristics

and original lifestyle variables. To test the statistical significance among three

clusters on demographic and socio-economic variables, a Chi-square analysis

was used. To test the statistical significance among three clusters on

ethnocentrism and product attribute importance, a one-way ANOVA was

performed. Table VI shows the characteristics of the clusters. After analyzing

the characteristics, the first cluster of consumers showed the least degree of

ethnocenti-ic tendencies, indicating these consumers would most likely evaluate

a foreign-made product on its own merit and on the basis of the utility it offers

to them, rather than on where the product is manufactured or assembled.

Respondents in this cluster are mostly college educated and high income

earners. Quality, workmanship, prestigious brand name and style are very

important for these consumers, but price is not important to this group. These

consumer product demands and requirements are similar to those of consumers

in western nations. Cluster I is labeled as Liberals/trend setters. On the other

hand, clusters II and III are labeled as Moderates/survivors and Traditionalist/

conservatives respectively. Consumers in these segments are highly

ethnocentric and their demands and needs are not as sophisticated as the

consumers' demands in cluster I. A distinguishing characteristic of cluster III

consumers is that this group is mostly female. In their families, car purchases

are made by males. Prestigious brands and style are not important. Family

finances are managed mostly by males and price is very important. Study

results further indicated that non-ethnocentric Turkish consumers tended to

have significantly more favorable beliefs, attitudes, and intentions regarding

imported products than ethnocentric Turkish consumers.

Conclusions

While the present study should be considered exploratory, findings of the

study showed that several lifestyle dimensions exist among Turkish

consumers which have an influence on their ethn(x;entric buying tendencies.

These dimensions were fashion consciousness, leadership, family concern,

health consciousness, carefreen^s, community consciousness, cost

consciousness and practicality. Four major dimensions found among

consumers of the western nations such as fashion, leadership, community

concern and health consciousness do also exist as major lifestyle dimensions in

Turkish consumers. Significant con-elations were found between the lifestyle

dimensions of Turkish consumers and their ethnocentricism levels. Fashion

consciousness and leadership were statistically negatively correlated with the

ethnocentrism score. In other words, less ethnocentric Turkish consumers are

more fashion conscious and leadership oriented or vice versa. On the other

hand, family concern and community consciousness factors were significantly

positively correlated with the ethnocentrism score. That is, Turkish consumers

who are very family concerned and community oriented are more ethnocentric,

indicating that these consumers would be most likely to prefer purchasing

Lifestyle

dimensions and

ethnocentrism

483

European

Journal of

Marketing

33,5/6

484

domestic products. This information has significant implications for the

marketers who currently operate in Turkish markets, or are planning to enter

into the development of promotion in the near future, regarding packaging and

pricing strategies for their products.

After analyzing the result of cluster analysis, it is found that consumers who

are classified as non-ethnocentric (cluster I) have very similar demand and

requirements as of their counterparts in the western nations. This finding

shows that the middle and high income consumers, irrespective of nationality

and country of residence, demonstrate similar, if not identical, behavioral

tendencies. This is consistent with the findings of Lynch (1994) and Svennevig

et al (1992) that with the emergence of market economies in newly

industrialized countries, distinct market segments are emerging in response to

increased business opportunities. In many of these countries, an extremely

affluent market exists along with low-income market segments. The affluent

segment's consumption can be characterized as conspicuous with strong

preferences for shopping for western goods (Lynch, 1994; Svennevig et al,

1992). Therefore, it appears that companies can standardize their marketing

strategies across nations while targeting these market segments. Syncrotic

decision making, brand name, and choice of products were considered very

important by cluster I (Liberals/trend setters) consumers, and they paid more

attention to fashion and design. Cluster I consumers may be considered very

important for marketers of major consumer products such as cosmetics,

sporting goods, household appliances and electronics and may require very

little or no modifications in the marketing strategy and approach.

On the other hand, the other two market segments cluster II (moderates/

survivors) and cluster III (traditionals/conservatives) are similar to each other.

Consumers in these segments are highly ethnocentric and their demands are

not as sophisticated as the consumers' demand in cluster I. The main

differentiating factor is the primary gender groups found in each segment. The

consumers in these segments are mainly traditional consumers with low

consumer sophistication and high ethnocentrism. The relationship between

ethnocentric tendencies attitudes and imports may be moderated by product

necessity (Sharma et aL, 1995). Hence, successful marketing strategies in these

segments require significant product and message modifications. One way to

overcome this unfavorable impact of consumer ethnocentricity on attitudes

toward imported products may be to stress product attributes, benefits, and

superior aspects of the product by underplaying the product's country of

origin. Companies in their efforts to expand their share of this segment of the

market will have to be need oriented. That is to say that international firms

need to undertake more marketing research for the assessment of the

ethnocentric consumer needs and filter this information and data through their

research and development departments. Through this kind of effort,

international firms will be able to develop appropriate products for the needs of

ethnocentric consumers.

References

Albaum. G. and Peterson, R.A. (1984), "Empirical research in international marketing".

of International Business Studies, Vol. 15, pp. 161-73.

Anderson, W.T. and Golden, L. (1984). "Life-style and psychographics: a critical review and

recommendation", in Kinnear, T. (Ed.), Advances in Consumer Research, XI, Association

for Omsumer Research, Ann Arbor, MI, pp. 405-11.

Banister, J.P. and Saunders. J.A. (1978), "UK consumers' attitudes towards imprats: the

measurement of national stereotype image". European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 12 No. 8,

pp. 562-70.

Baumgartner, G. and Jolibert (1978), "The perception of foreign products in France", in Hunt,

H.K. (Ed.), Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 5. Association for Consumer Research.

Ann Arbor, MI, pp. 603-5.

Bilkey, Warren, J. and Nes, E. (1982), "Country-of-origin effects on product evaluations", yourHd/

of International Business Studies, Vol. 13, Spring/Summer, pp. 88-99.

Cattin, P., Jolibert, A. and Lohnes, C. (1982), "A cross-cultural study of 'made in' concept"./ottmfl/

of International Business Studies, Vol. 13. pp. 13141.

Chasin, J.B., Holzmulter, H. and Jaffe. E.D. (1988), "Stereotyping, buyer familiarity and

ethnocentrism: a cross-cultural analysis". Journal of International Consumer Marketing,

Vol.l,No.2,pp.9-29.

Cordell, V. (1992), "Effects of consumer preferences of foreign sourced products". Journal of

International Business Studies, Vol. 23 No. 22, pp. 251 -69.

Darling, JJ^. and Kraft, F.B. (1977), "A competitive profile of products and associated marketing

practices of selected European and non-European countries". European Journal of

Marketing, Vol. 21 No. 3, pp. 17-29.

Davis, H. and Rigaux, B. (1974), 'Perceptions of marital roles in decision processes", Journal of

Consumer Research, Vol. 1, June, pp. 51-62.

Dickerson, K.G. (1982), "Imported versus US-produced apparel: consumer view^ and buying

patterns". Home Economics Research Jour^ial, Vol. 10, pp. 241-52,

Durvasula, S., Andrews, J.C. and Netemeyer, R.G. (1992), "A cross-cultural comparison of

consumer ethnocentrism in the United States and Russia". Proceedings of the American

Marketing Association, Summer, pp. 511-12.

Han, CM. (1988). "The role of consumer patriotism in the choice of domestic versus foreign

proAnds" .Journal of Advertising Research,]une-]\}\y, pp. 25-32.

Han, CM. (1990), "Testing the role of country image in consumer choice behavior", European

Journal of Marketing, Vol. 24 No. 6. pp. 24-39.

Herche, J. (1992), "A note on the predictive validity of the CETSCALE"./o«mfl/ of the Academy of

Marketing Science, Vol. 20, Summer, pp. 261-4.

Hong. S. and Wyer, R.S. (1989), "Effects of country of origin and product-attribute information

processing perspective",yo«ma/ of Consumer Research, Vol. 16, pp. 175-87.

Johanson, }K., Douglas, S.P. and Nonaka. I. (1985), "Assessing the impact of a)untry of origin on

product evaluations: a new methodological perspective". Journal of Marketing Research,

Vol. 22. pp. 388-96.

Kaynak. E. and Kara. A. (1996a), "Consumer ethnocentrism in an emerging economy of Central

Asia", American Marketing Association Summer Educators' Conference Proceedings, San

Diego, CA, pp. 514-20.

Kaynak, E. and Kara. A. (1996b). "Consumer life-style and ethnocentrism; a comparative study in

Kyrgyzstan and Azarbaijan", 49th Esomar Congress Proceedings, Istanbul, pp. 577-%.

Lifestyle

dimensions and

ethnocentrism

485

European

Journal of

Marketing

33,5/6

Utour, M.S. and Henthome, T.L. (1990), "The PRC an empirical analysis of country of origin

product perceptions",yrt«mfl/ of Intertuttional Consumer Marketing, Vol. 4. pp. 7-35.

LeVine, R.A. and Campbell, D.T. (1974), "Ethnocentrism: theories of conflict", Ethnic Altitudes

and Group Behavior, John Wiley, New York. NY.

Lynch. R. (1994). European Marketing: A Strategic Guide to the New Opportunities, Irwin, BunRidge. IL.

486

McLain. S. and Stemquist. B. (1991), "Ethnocentric consumers: do they buy American?", yoMmo/

of International O)nsumer Marketing, Vol. 4 No. 1, pp. 39-57.

Mihalyi, L.S. (1984), "Ethnocentrism vs. Nationalism: origin and fundamental aspects of a major

problem for the future", Hombodit Journal of Social Relations, Vol. 12 No. 1, pp. ^ 1 1 3 .

Milligan, G.W. and Cooper, M.C. (1985), "An examination of procedures for determining the

number of clusters in a data set", Psychometrika, Vol. 45, pp. 32542.

Mitchell, A. (1983). The Nine American Ufe-styks, Macmillan Publishing Company, New York,

NY.

Morelio, G. (1984), "The 'made in' issue: a comparative research on the image of domestic and

foreign products", European Research, Vol. 12, January, pp. 5-21.

Nagashima, A. (1970), "A comparison of Japanese and US attitudes towards fweign products'*,

Journal of Marketing, Vol. 34, January, pp. 69-74.

Narayana, CL. (1981), "Aggregate images of American and Japanese products: implication on

international marketing", Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. 16, pp. 31-5.

Netemeyer, R., Durvasula. S. and Lichtenstein, D. (1991), "A cross-national assessment of the

reliability and validity of the CETSCALE". Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 28,

pp. 320-7.

Papadopoulos. N. and Heslop. L. (1993), Product and Country Images: Research and Strategy,

The Haworth Press, New York, NY.

Papadopoulos, N., Haslop, L. and Bamossy. G. (1990), "A comparative image analysis of

domestic versus imported products". InternationalJournal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 7

No. 4, pp. 283-94.

Parameswaran, R. and Pisharodi, R.M (1994), "Facet of country of origin image: an empirical

assessment",Joumai of Advertising, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 43-56.

Reirson, C (1966), "Are foreign products seen as national stereotypes?". Journal of Retailing,

Vol. 42, Fall, pp. 3340.

Rushton. J.P. (1989), "Genetic similarity, human altruism, and group selection". Behavioral and

Brain Sciences, Vol. 12, pp. 503-59.

Sevenevig, M., Pounds, J. and Olszewski, M (1992), "Researching Central and Eastern Europe".

Marketing and Research Today, Vol. 20 No. 3. pp. 200-5.

Sharma, S., Shimp, T. and Shin, J. (1995), "Consumer ethnocentrism: a test of antecedents and

modemtors", Jourtial of tiie Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 26-37.

Shimp, T..^. and Sharma, S. (1987). "Consumer ethnocentrism: construction and validation of the

CETSCALE",JoumaI of Marketing Research, Vol. 24, August, pp.280-9.

Thorelli, H.B., Lim, J. and Ye, J. (1988), "Relative importance of country of origin, warranty and

retail store image on product evaluations". International Marketing Review, Vol. 6 No. 1,

pp. 35-46.

Tongberg, R.C (1972), "An emprical study of relationships between dogmatism and consumer

attitudes toward foreign products". Dissertation, Pennsylvania State University.

Tse. D. and Gom, G. (1993), "An experiment on the salience of country of origin in tbe era of

global hrznds", Journal of International Marketing, Vol 1 No. 1, pp. 57-76.

W a n g , C. a n d L a m b . C (1983), " T h e impact of selected environmental forces u p o n c o n s u m e r s '

Lifestyle

willingness to b u y foreign products",/owrwa/ of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. l i t •

j

No. 2, pp. 71-84.

aimensions ana

Wells, W.D. (1975), "Psychographics: a critical reviev/". Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 12.

ethnOCentrism

May, pp. 196-213.

Wells, W. and Tigert, D. (1977), "Activities, interests, and opinions". Journal of Advertmng

Research, Vol. 11 No. 4. pp. 27-35.

Westfall, R. (1962). "Psychological factors in predicting product choice". Journal of Marketing,

April, pp. 3440.

Yavas. B. and Alpay, G. (1986), "Does an exporting nation enjoy the same cross-national

commercial image". Intemationaljoumal ofAdvertising, Vol. 2. pp. 109-19.

^^^^^^^^