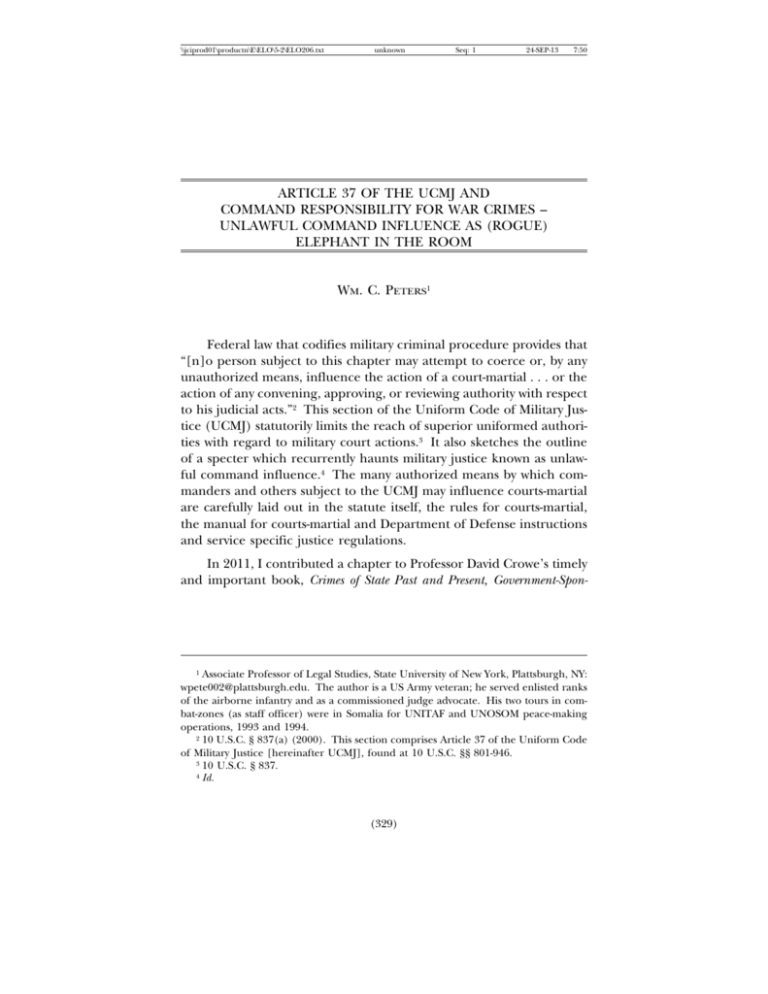

article 37 of the ucmj and command responsibility

advertisement