This Moment Kristen Cunningham I remember being awakened in

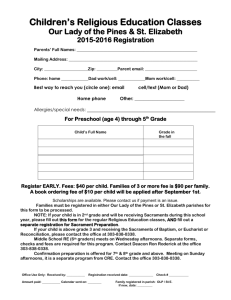

advertisement

This Moment Kristen Cunningham I remember being awakened in the middle of the night and rushed into the car. My brother and I were confused and sleepy, so we napped on the way to the hospital. My mom drove and my dad was in the passenger seat--lines of pain etched into his brow and around his eyes. He clutched a pillow to his stomach and tried not to moan. I remember this, not once, but twice, maybe even three times. The midnight drive to the hospital, the pregnant air of the waiting room, the concerned grandparents, it all told me something was wrong. Yet I was young, only a third grader. I accepted what happened around me, all of it. It must be part of life. So I accepted that my father got sick. I accepted the sterile smell of hospitals. I accepted the beds of other’s homes. I accepted that my mom spent nights in the hospital with my dad. I accepted the discomfort of crying family members. I accepted my father’s growing weakness. I accepted his skin turning yellow. I accepted the funny smell that came from him. I accepted that he didn’t have the strength to speak any longer. I accepted the distance between us, hugging him as if he wasn’t the man that has raised me. I accepted that the get well cards and cheap gifts were all obviously in vain. And then as I crept in the living room one day to retrieve our cat, I saw my family helping him from the recliner in the living room to the stretcher in the living room, the one that had become his bed as of the past few days. I heard him moaning in protest as everyone tried to understand what he wanted. They must have thought he wanted to lie down, though later I learned that the last act a person wants to do before he dies is use the restroom to relieve the body of any waste or toxins before finally letting go. My mom stepped into my brother’s room to ask us if we wanted to say goodbye, and I had to accept what I didn’t want to accept. He was gone. I shook my head as if I could deny it, and stepped backwards silently. My brother began to cry and my mother held him tight, tears escaping her eyes and streaming down her cheeks to that trembling chin I inherited. I began to accept it when I would wake in the middle of the night to hear my brother crying, and my mother would come to comfort him and end up in tears as well, but never me. I’d watch them hugging and feel sick to my stomach; my tears never came. I’d try to peel myself away and go back to my room without being noticed. What I had trouble accepting was that he was really gone. I would be playing happily with a friend, and then it would hit me again--my dad is dead. I would be reading a book in school and I would realize it again--my dad is dead. The nauseating waves of realization hit me a dozen times until it stopped. And even then, when I had accepted that my dad was gone, I didn’t cry. Fast forward three years to sixth grade. I was writing in a journal for my English class one night. I wrote about my dad. I had always known my dad and the empty space he left behind were a big part of my life, regardless if I felt so or not. I wrote about how he had passed, and I wrote about how I had never cried. I wrote about how I did on occasion cry though, if I scrapped my knee or didn’t get what I want. I wrote about how I was a monster for it. I wrote about how I cared about myself more. And at some point, for the first time, I cried for my dad-- for missing him, for having to grow up and change without him here to see, for telling my mom I’d rather it had been him than her, for the empty father’s days, for the fact that my father daughter dance could never be what it was supposed to be, for forgetting my memories of him and forgetting what his face looked like. This all has taught me that death doesn’t just steal a person from your life; it gnaws away at his memory and face; I can no longer remember what my father looked like apart from the pictures left behind. It taught me that there’s never going to be enough time to tell a person everything you would like to before he’s gone. It taught me how hard it is for my mom to raise my brother and me on her own. It also taught me how much I truly love my mom, and that I wouldn’t know what to do without her. It taught me that there’s more to life than what we get here on earth. It taught me that death isn’t always a tragedy; it can be a sweet release from the pains of this world. It taught me that I haven’t seen the last of my father. It taught me that he’s still here--in me when I bite my nails persistently, or when my brother watches his old movies, or when we all make chocolate shakes and sit down for a movie night. It taught me that everyone will pass, and the time we have should be spent happily, making the most of what we’re given. “Yesterday is gone and tomorrow may never come. All you have is this moment.” - Bob Russell.