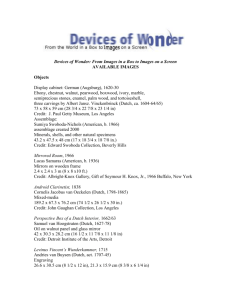

A View of the Dutch IPO Cathedral

advertisement