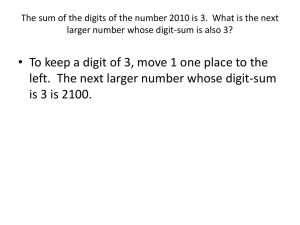

2. Swedish monetary standards in a historical perspective1

advertisement