CHAPTER 6:

advertisement

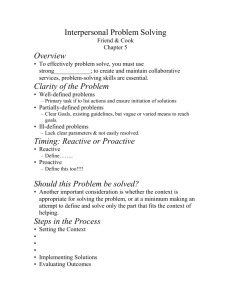

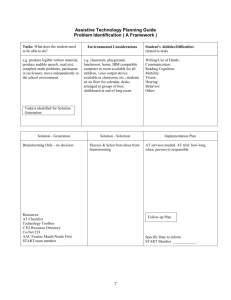

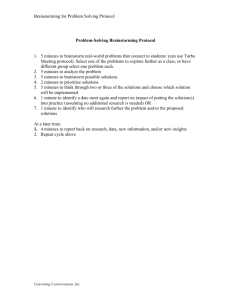

CHAPTER 6: PROBLEM & SOLUTION IDENTIFICATION Chapter Outline 9. 1. 2. 3. Problem & solution identification issues PSID vs. decision-making Identifying problems vs. solutions Time orientation/reactive vs. proactive Larson’s Single Question Patterns 10. Posner & Simon’s Hierarchical Strategies 11. Cummings, Long, & Lewis’ Elaborated Hierarchical Strategy Principles for Problem Solving Avoid selection bias Continuous information gathering Avoid premature evaluation Set acceptance criteria Support differentiation Maximize involvement 12. Using Teams Teams vs. Committees When to Use Teams Team Advantages Team Purpose Team Composition Process Action Team Membership Dewey’s Reflective Thinking 4. Koehler’s RPIM & Cause/Effect Strategy 5. Koehler’s PAIM & Goal Achievement Strategy 6. Brainstorming 7. Gordon & Prince’s Synectics 8. Turner’s Inertia Activation 13. Decision Tools for Teams Typical Pattern for Tool Application Uses of Tools Flowcharting Brainstorming Techniques Aspect Grouping Interrelationship Digraph Fish Bone Task & Objective Plan Problem & Solution Identification Issues Organizational problem and solution identification is most effective when managers have a variety of problem-solving models to select from. It is problematic when the same technique is used all of the time because some approaches are best in certain circumstances and worst in others. Consequently, this chapter will describe 10 different models that are commonly used. PSID vs. decision-making. Problem-solving or problem and solution identification (PSID) is commonly viewed as a general process that begins with a felt need and results in selecting a solution to satisfy that need. Often, the terms “problemsolving” and “decision-making” are used interchangeably in work settings. However, 6-1 these concepts are different. Problem solving is a broad process that involves all communication functions. In contrast, decision-making, or selecting a course of action, is the consequence of problem identification, solution identification, and solution selection. Identifying problems vs. solutions. Identifying problems and identifying solutions are specialized activities that constitute the PSID communication function. Past research and practice, however, seldom differentiates between these activities and the consequent impact on decisions that are made. So, we initially need to examine how time orientation influences perspective. Time orientation. One way to differentiate among PSID models is by time orientation. Some models are reactive, post-hoc, a’ posteriori, or, simply, “after the fact.” Other approaches are proactive or a’ priori (Koehler, 1975). Thus, PSID models may be placed along a continuum with proactive and reactive as end-points (see Figure 6-1). Koehler described short-term decisions as reactive because they are responses to unanticipated, occasionally negative, events. Proactive activities are long-term organizational planning processes and procedures. They are typically tied to a Reactive Approach 1. Short-term decisions 2. Need for immediate attention 3. “fire fighter” mentality Proactive Approach 1. Long-term decisions 2. More time 3. “preventive maintenance” mentality Figure 6-1 sequence of steps that are followed in order to reach goals. Visualizing reactive and proactive as opposite ends of a continuum highlight differences in perspective. Reaction represents a “fire fighter” approach to problem solving. In other words, one waits until something goes wrong, and when the problem is discovered, a procedure to solve the problem is applied. In contrast, proactive approaches do not wait for a dysfunction to occur before a procedure is implemented. 6-2 Instead, a proactive manager would look for potential obstacles or methods of improvement – a type of “preventive maintenance” approach. By analogy, you take a reactive approach to healthcare when you buy medicine to treat flu symptoms you have acquired. Had you been proactive with respect to catching the flu, you would have gotten a flu shot “before the fact!” Principles for Problem Solving Each model discussed in this chapter contains unique characteristics and assumptions. Yet, successful application requires adherence to a shared set of communication principles: 1. Avoid model selection bias. This principle can take many forms. For example, most organizations use reactive models exclusively. Why? The reasons are many and include – fire fighter mentality, lack of appreciation for inherent benefits of different models, interpersonal relationship weaknesses, poor communication skills, refusal to delegate responsibility and authority, etc. This PSID “rut” assumes past answers to problems will always work in the future. There is value in learning from the past; however, to hold rigidly to this assumption is to deny the dynamic nature of PSID processes and the inevitability of changing conditions. 2. Continually gather information. Regardless of the model or time orientation, information gathering and analysis is critical. Quite often problems are poorly defined, unworkable solutions are selected, or organizational goals that play key roles in prioritizing problems and solutions lack clarity. Thus, continual research, or avid use of the adaptive subsystem, recognizes the dynamic nature of organizations. It is critical and basic to effective problem solving. Poor information management is often the culprit that inhibits this principle. 3. Avoid premature evaluation. We are often in such a rush to make a decision and reduce tension that we neglect to use our critical thinking skills – we conclude a problem is defined before it is, oversimplify our analysis, and reach into our “bag of tricks” for a solution. Why? There are many reasons – intolerance for 6-3 ambiguity, pressure to produce, desire to eliminate irritant, and short-term thinking without consideration of long-term consequences. 4. Set acceptance criteria before making a decision. In both proactive and reactive modes, boundaries are necessary. For example, important time is often wasted discussing solutions that are unaffordable or unmanageable. This happens because decision selection criteria aren’t agreed upon early. Beyond wasting time, unstated criteria many lead to PSID conflicts, unknown to participants at the time of discussion, because individuals often are working from different sets of criteria. 5. Establish an environment conducive to differentiation. Low trust levels lead to hidden agendas, lack of disclosure, deceptive practices, and distorted or retarded information-gathering outcomes. Differentiation is, put quite simply, the communication of differences. Differences in viewpoint, perception, knowledge, and values need to be expressed and properly processed during PSID. Healthy differentiation allows disagreement, consideration of alternatives, and advocacy of different perspectives without feeling defensive or threatened. Research indicates that differentiation is critical to the quality and efficacy of PSID outcomes (Folger & Poole, 1984). 6. Maximize involvement. Clearly, there are times when involvement in PSID should be limited. However, when decisions are made that have widespread ramifications, they are much more difficult to implement if participant “buy in” was not achieved during the PSID process. Sometimes decision-makers fear that participation will inhibit their ability to employ a preferred outcome. Consequently, they often suggest that others “. . . simply do not have the knowledge or experience needed to come up with a solution.” While this may be true in some instances, this adage is often abused and employees are not involved when they should be. Often, decision-makers acquire this characteristic as a management style, exclaiming (usually silently, but overtly through behaviors), “I am hired to make decisions and you are hired to carry them out because I know more than you do!” While there may be some validity to this assertion, increasing complexities in organizations, limits in human information 6-4 processing, and resistance to change tendencies have significantly reduced the viability of this position. In other words, managers should consider the following caveats: • Today’s manager cannot know all that is needed to adequately solve problems and anticipate barriers to future goals. • Employees are more involved in their work when they participate in problem solving processes. • Employees who participate in problem solving processes report higher levels of job satisfaction. • Increased participation enhances information-gathering activity. • Increased participation increases operational degrees of freedom. Now that PSID issues and principles Relative Complexity of PSID Models Elaborated Hierarchical Hierarchical Single Question Patterns Inertia Activation Synectics Brainstorming Goal Achievement Cause/effect Reflective Thinking have been discussed, we will devote the MOST COMLEX remainder of the chapter to describing 10 specific models. These models are presented in order, from the least to most complex (figure 6-2). Here, LEAST COMPLEX increasing levels of complexity are Figure 6-2 based upon each subsequent model having the capacity to assume the characteristics or use the elements in each previous model. Reflective Thinking How We Think (Dewey, 1910) was Reflective Thinking the catalyst for describing steps in problem 1. Felt difficulty (problem ID) 2. Difficulty isolated & defined (problem ID) 3. Solutions suggested (solution ID) 4. Solutions examined by criteria (solution ID) 5. Solution selected & implemented (solution ID) 6. Based on outcome, solution retained or rejected; if rejected, process repeated (PSID) solving. In this book, a step-by-step cognitive, response to individual problems was suggested and called the “reflective thinking process.” Reflective thinking Figure 6-3 consisted of 6 steps (see Figure 6 -3). This 6-5 model shows a concern for problem and solution identification and implies an inherent value in collective decision-making. A key part of this model is in step 4. What should be the criteria for identifying solutions? Are there any criteria for identifying and defining the perceived difficulty in step 1? Criteria and felt difficulties are difficult to describe until the organization’s culture – values and beliefs – are assessed. Dewey’s work has had a tremendous impact on PSID theorists. Many models are little more than a slight modification of Dewey’s work. The strength of this approach is that it is logical, time-tested, and works well for personal problem solving. Its weakness is that it assumes needed information is accessible. This assumption, however, is not always valid. For example, contemporary research has established that humans are not capable of gathering, analyzing, and organizing all information needed for perfect problem solving. RPIM or Cause/Effect Strategy Koehler’s Reactive Problem Identification Model (RPIM) is a cause/effect strategy (Figure 6-4). These strategies are used often everyday. They direct the user to identify the cause of a problem and then act to remove the cause. Then, the problem should disappear. There are 3 steps in these strategies: (1) identify an undesirable condition, (2) define the cause of the condition (problem ID), and (3) identify ways to remove the cause and implement (solution ID). RPIM extends these steps. It begins with defining expectations, which are “desirable” organizational outcomes. If productivity is a high priority, then it becomes a significant part of expected outcomes. The second step is to describe what occurred. This includes defining conditions or situation that Koehler’s RPIM UNANTICIPATED NEGATIVE REACTION 1. Define expectations 2. Describe outcomes 3. Identify effects on personal & organizational goals 4. Identify negative effects, if any 5. Identify cause of negative effects CAUSE IS THE PROBLEM Figure 6-4 6-6 deviated from expectations. Step 3 is concerned with the impact on personal and organizational goals. Step 4 consists of identifying negative effect. Step 5 requires definition of specific element that caused the negative effect. Then removal of the causes becomes the solution. There is a certain “street-wise” logic to cause/effect strategies. Unfortunately, problems rarely have one cause. If this is the case, some of the more complex models should be used. PAIM or Goal Achievement Strategy Goal achievement strategies are common when there is a dominant organizational belief that the organization is a group of people collaborating to achieve an outcome. This approach differ slightly from the cause effect approach, following this 3-step question pattern: (1) what is the organization’s objective/goal, (2) what frustrates or is a barrier to achieving the goal (problem ID), and how can the barrier(s) be removed (solution ID). Here the difference is obvious in that cause-effect models tend to focus on problems inherent in a previous condition, assuming that previous causal conditions are the problems. Goal achievement strategies, however, assume that the organization is goal oriented, that future or present conditions are causal agents, and these causal agents are the problem. Here the solution is to remove current and potential barriers. Often, cause/effect decision makers move to a goal achievement strategy when they say, “what can we do to insure this circumstance doesn’t happen again?” It is important that goal-setting models project future barriers. This requires clear, mutual understanding of short, intermediate, and long run goals. However, this is often an organizational weakness. Koehler’s PAIM Overcoming this weakness requires carefully designed, at least annual, GOAL 1. Determine obstacles to goal achievement long-range planning. When this is 2. Identify controllable obstacles that affect outcomes done, Koehler’s Pro-Active 3. Define causes of controllable obstacles Identification Model (PAIM) can make CAUSE IS THE PROBLEM an excellent contribution to Figure 6-5 organizational success (figure 6-5). 6-7 PAIM begins with determining all possible obstacles an organization might encounter in achieving a goal. Step 2 focuses on defining obstacles that are controllable. Step 3 is a comprehensive definition of all obstacles to goal achievement – these are the problems to be identified. The steps a similar to the cause/effect model, yet are also quite different because they are a’ priori or “before the fact.” It is common, for example, to combine RPIM and PAIM models. Brainstorming Decision theorists have known for some time that PSID is difficult because employees are afraid to risk public evaluation of their ideas. To combat the fear of public scrutiny, they propose that people should be permitted to generate ideas in an open and free environment. In this way, creative, high-quality solutions can be realized. There are many techniques used to achieve this end. A common approach is to write down an idea and post it on the wall. This is called silent brainstorming. It is common for a group of 5 or 6 people to generate 60 or 70 ideas in a 5-minute silent brainstorming session. Brainstorming has 3 steps. Step 1 is free expression of ideas without evaluation. Step 2 is creation of an environment that assures full participation of all during the interchange of ideas. Obviously, the trust level must be high in order to achieve step 2. Step 3 is evaluation. This begins only when all ideas have had complete and unevaluated expression. Nothing in these steps focuses on identifying problems or solutions. This is a process for generating these – it is multi-purposive. Hence, it is more complicated to use since it is done in conjunction with other models. Brainstorming has been often studied in terms of its capacity to lead to high quality decisions. Overall, evidence is mixed – in some cases it works, in others it doesn’t. Many have challenged it for being time consuming. However, new methods (e.g., silent brainstorming) have recently been found as much more productive when compared to conventional discussions. It seems apparent that the approach, when 6-8 applied correctly in a supportive environment, will produce more ideas than other methods. Whether or not the ideas are applied successfully is beyond the scope of this model. Synectics Gordon (1961) and Prince (1968) developed synectics. This model is similar to brainstorming, but is a bit more complex because it is based on a different assumption. Synectics assumes that beyond the employees, themselves are obstacles to PSID. To overcome this obstacle, the model allows and encourages the use of an active imagination in its first step. Step 1 consists of fantasizing what you would do if you could to improve or change conditions in the organization (solution ID). Step 2 consists of evaluating the solution’s strengths and weaknesses (solution ID). Step 3 is a repeat of the fantasize-evaluation sequence until consensus develops on one or more solutions, followed by a consideration of how the solution may be implemented (problem ID). This is the method used by many futurists who ponder the impact of technology. For example, an entrepreneur may fantasize about solution (Internet and World Wide Web) and what problems the solution could solve (e.g., information accessibility, marketing channel inefficiencies, etc.). Synectics represents a reversal from other sequences with the solution being explored first, followed by problem identification. This strategy assumes that when peoples’ imaginations are “fired up,” they can generate creative solutions to problems never before experienced. Inertia Activation Some experts in labor negotiations claim that the “two warring factions – often the union and the company – should be locked up I a room and not allowed to come out until they have an agreement.” This assumes that after a period of forced inactivity, or inertia, a sudden burst of energy will follow, and that this activity should produce 6-9 meaningful results (Turner, 1964). Turner described inertia as following this general process: Step 1: Place people who share the same values and preoccupations together (value convergence) to identify problems and solutions. OR, select a group composed of those with different values and preoccupations (value divergence). Step 2: Activate values and predispositions by directing the group’s attention toward a specific situation or event requiring attention. Step 3: When sufficient levels of frustration are generated by agitation (by the assigned task), the inert tendency to avoid activity will be followed by an energy release or explosion. This was a commonly used teaching technique during the 1960’s and 1970’s on college campuses. The typical classroom reaction was silence. Within a short period of time, however, class members would mobilize in order to meet deadlines (often a group project). Single Question Patterns Single Question Patterns Single question patterns (Larson, 1969) begin with the question: What is the problem? (see figure 6 -6) Then, the single question is divided into parts or sub- 1. What single question, which when answered, means the organization knows how to accomplish its purpose 2. What sub-questions must be answered to the question in #1 3. Is there sufficient information (if yes, go to #5; if no, go to #4) 4. What are most reasonable answers to questions 5. If sub-question answers are adequate, what is best solution 6. How will this be implemented Figure 6-6 questions. Step 3 calls for information gathering, followed by an assessment of solution feasibility in step 4. This approach is similar to the process of preparing a speech outline, or constructing an argument in a debate: (1) decide on the specific theme and/or purpose, (2) divide the speech into its main points or topics, and (3) support each main topic with evidence in the sub-topics. This is actually the process of “chunking” 6-10 described in chapter 5. Often, this model is used with brainstorming, either in reactive and proactive circumstances. Hierarchical Strategies Posner (1963) and Simon (1969) made significant contributions to this approach suggesting 3 general steps. Step 1 is to structure the problem into parts of chunks (problem ID). Step 2 consists of ordering the chunks, hierarchically, from most to least important (problem ID). Step 3 is selecting a solution that matches the hierarchical importance of the problem (solution ID). Advocates of this approach view other models as inadequate citing the assumption of sufficient information. In contrast, hierarchical approaches argue that there are degrees of information (consistent with information theory). Thus, the approach recognizes levels of complexity in PSID. The model gives equivalent emphasis to selecting a solution “good enough” for a problem, a concept that Simon labeled as the process of “sufficing.” Several conditions in organizations make this approach is very difficult to use. For example, problems are often too complex to simply select a solution for each “chunk” or part. Furthermore, the amount of available information for each part varies and often problem areas overlap. Finally, the act of communicating to make a decision is inherently limited by characteristics and skills of those persons involved. How, then, can a hierarchical strategy be applied to complex problems? When communication principles we discussed in chapters 1 through 6 are combined with this model, the consequence is the elaborated hierarchical model. This combination of elements, firmly entrenched in systemic thinking, provides an approach for capitalizing upon the advantages of the previously described models. 6-11 Elaborated Hierarchical Model The elaborated hierarchical model (EHM) assumes multiple, overlapping causes of problems. The approach accents an initial step (Step 1 ) of identifying the problem, but also emphasizes identifying problem complexity: How many problems require attention (see figure 6-7); how many problem parts are there? In this way, problemrelated information is chunked in Elaborated Hierarchical Model usable, meaningful ways. Without information chunking, the decisionmaker cannot deal with the typical vast amounts of information that complex organizations contain. 1. Identify problem according to complexity 2. Locate problem in context 3. Order sub-problems according to importance. Is each important enough to justify an investment of time & energy 4. Identify solutions to problems 5. Assess possible consequences for solution implementation Figure 6-7 Step 2 requires locating the problem in context. In other words, problem ID begins by examining intraorganizational elements first, followed by an analysis of inter-organizational relationships; likewise, intra-group or interpersonal contexts are examined first, followed by inter-group or inter-departmental context assessment. Cyert and March (1963) pointed out, “ . . . a failure of local search can lead decision-makers to more complex search strategies,” often making a problem far more complicated and timeconsuming than it should be. Communication concepts and principles provide the basis for problem location (see figure 6-8). There are 3 dimensions of a problem: system location, content, and function. System location may be intrinsic or extrinsic to the organization, i.e., internal or external. Content is either work or person related. Functional dimensions are the consequence of information exchange, problem/solution identification, behavior regulation, and conflict management. Thus, application of this model begins is very analytic, with full recognition of the potential for complexities. Contextual location, then, consists of answering specific questions: is the problem or problem part inside or outside the organization; is the problem or problem part work- or person-related; is the problem related to information 6-12 exchange, problem-solving processes, behavior management, or conflict. When combined, this combination of three dimensions produces 16 specific problem contexts. The value of multi-dimensional contextual location is that problem complexities and interactions are more likely to be considered. Conflict management Function Behavior regulation Problem & Solution ID Information Exchange Internal System External WORK PERSON Content Figure 6-8: 16 problem contexts The third step required ordering by importance. Here, 3 questions are asked: are the internal problems more important than external problems; are problems related to work more important than those related to personal needs and goals; which problems are most to least important – information exchange, problem/solution identification, behavior regulation, conflict management? It’s important to remember that societal, organizational, and personal values and beliefs will influence rank ordering. 6-13 Step 4 requires solution identification for each problem in the same location or context. Solution implementation follows the priority of importance established in step 3. Step 5 is analysis of potential consequences for each solution to be implemented. This is an important step because a new solution might induce new problems. For example, one organization we are aware required a 10% budget reduction across all departments. One executive proposed that all probationary employees be terminated. When this solution was examined for its potential, it was discovered that such a move would have virtually eliminated the information technology division. Needless to say, that part of the plan was dropped. This model is the most complex because it can be reactive or proactive and its users can incorporate all of the other models during its application. The advantage of the approach is that it recognizes complexities inherent in effective decision-making. The weakness is that it is complex, requiring skilled communicators operating in a supportive, trusting environment. Using Teams Teams vs. Committees When to Use Teams Team Advantages Team Purpose Team Composition Who should be on a Process Action Team Membership Decision Tools for Teams Typical Pattern for Tool Application Uses of Tools Flowcharting Brainstorming Techniques Aspect Grouping Interrelationship Digraph Fish Bone Task & Objective Plan 6-14