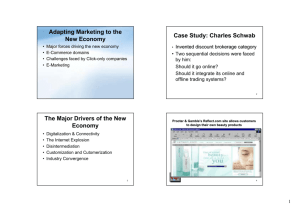

The E-Marketing Mix

advertisement