a history of antisocial personality disorder in the

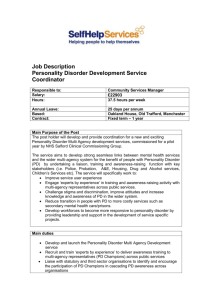

advertisement