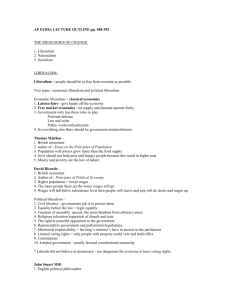

Eric Helleiner, Economic Nationalism as a

advertisement