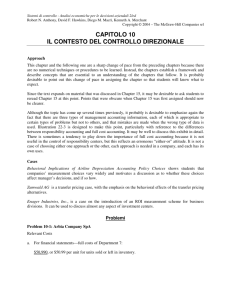

1–1 How does managerial accounting differ from

advertisement

Programmazione e controllo - managerial accounting per le decisioni aziendali 3/ed Ray H. Garrison, Eric W. Noreen, Peter C. Brewer, Marco Agliati, Lino Cinquini © 2012, McGraw-Hill CHAPTER 9: Flexible Budgets and Performance Analysis CASE 9–26 Ethics and the Manager Lance Prating is the controller of the Colorado Springs manufacturing facility of Prudhom Enterprises, Inc. The annual cost control report is one of the many reports that must be filed with corporate headquarters and is due at corporate headquarters shortly after the beginning of the New Year. Prating does not like putting work off to the last minute, so just before Christmas he prepared a preliminary draft of the cost control report. Some adjustments would later be required for transactions that occur between Christmas and New Year’s Day. A copy of the preliminary draft report, which Prating completed on December 21, follows: Tab Kapp, the general manager at the Colorado Springs facility, asked to see a copy of the preliminary draft report. Prating carried a copy of the report to Kapp’s office where the following discussion took place: Kapp: Wow! Almost all of the variances on the report are unfavorable. The only favorable variances are for supervisory salaries and industrial engineering. How did we have an unfavorable variance for depreciation? Prating: Do you remember that milling machine that broke down because the wrong lubricant was used by the machine operator? Kapp: Yes. Prating: We couldn’t fix it. We had to scrap the machine and buy a new one. Kapp: This report doesn’t look good. I was raked over the coals last year when we had just a few unfavourable variances. Prating: I’m afraid the final report is going to look even worse. Kapp: Oh? Prating: The line item for industrial engineering on the report is for work we hired Sanchez Engineering to do for us. The original contract was for $160,000, but we asked them to do some additional work that was not in the contract. We have to reimburse Sanchez Engineering for the costs of that additional work. The $154,000 in actual costs that appears on the preliminary draft report reflects only their billings up through December 21. The last bill they had sent us was on November 28, and they completed the project just last week. Yesterday I got a call from Mary Jurney over at Sanchez and she said they would be sending us a final bill for the project before the end of the year. The total bill, including the reimbursements for the additional work, is going to be . . . Programmazione e controllo - managerial accounting per le decisioni aziendali 3/ed Ray H. Garrison, Eric W. Noreen, Peter C. Brewer, Marco Agliati, Lino Cinquini © 2012, McGraw-Hill Kapp: I am not sure I want to hear this. Prating: $176,000 Kapp: Ouch! Prating: The additional work added $16,000 to the cost of the project. Kapp: I can’t turn in a report with an overall unfavorable variance! They’ll kill me at corporate headquarters. Call up Mary at Sanchez and ask her not to send the bill until after the first of the year. We have to have that $6,000 favorable variance for industrial engineering on the report. Required: What should Lance Prating do? Explain. CASE 9–27 Critiquing a Report; Preparing Spending Variances Farrar University offers an extensive continuing education program in many cities throughout the state. For the convenience of its faculty and administrative staff and to save costs, the university operates a motor pool. The motor pool operated with 20 vehicles until February, when an additional automobile was acquired at the request of the university administration. The motor pool furnishes gasoline, oil, and other supplies for its automobiles. A mechanic does routine maintenance and minor repairs. Major repairs are performed at a nearby commercial garage. Each year, the supervisor of the motor pool prepares an annual budget, which is reviewed by the university and approved after suitable modifications The following cost control report shows actual operating costs for March of the current year compared to one-twelfth of the annual budget. The annual budget was based on the following assumptions: a. $0.16 per mile for gasoline. b. $0.05 per mile for oil, minor repairs, and parts. c. $480 per automobile per year for outside repairs. d. $900 per automobile per year for insurance. e. $8,610 per month for salaries and benefits. f. $2,400 per automobile per year for depreciation. The supervisor of the motor pool is unhappy with the report, claiming it paints an unfair picture of the motor pool’s performance. Required: 1. Prepare a new performance report for March based on a flexible budget that shows spending variances. 2. What are the deficiencies in the original cost control report? How does the report that you prepared in part (1) above overcome these deficiencies? (CMA, adapted) Programmazione e controllo - managerial accounting per le decisioni aziendali 3/ed Ray H. Garrison, Eric W. Noreen, Peter C. Brewer, Marco Agliati, Lino Cinquini © 2012, McGraw-Hill CASE 9–28 Performance Report with More Than One Cost Driver The Munchkin Theater is a nonprofit organization devoted to staging plays for children. The theatre has a very small full-time professional administrative staff. Through a special arrangement with the actors’ union, actors and directors rehearse without pay and are paid only for actual performances. The costs from the current year’s planning budget appear below. The Munchkin Theater had tentatively planned to put on five different productions with a total of 60 performances. For example, one of the productions was Peter Rabbit, which had five performances. Some of the costs vary with the number of productions, some with the number of performances, and some are fixed and depend on neither the number of productions nor the number of performances. The costs of scenery, costumes, props, and publicity vary with the number of productions. It doesn’t make any difference how many times Peter Rabbit is performed, the cost of the scenery is the same. Likewise, the cost of publicizing a play with posters and radio commercials is the same whether there are 10, 20, or 30 performances of the play. On the other hand, the wages of the actors, directors, stagehands, ticket booth personnel, and ushers vary with the number of performances. The greater the number of performances, the higher the wage costs will be. Similarly, the costs of renting the hall and printing the programs will vary with the number of performances. Administrative expenses are more difficult to pin down, but the best estimate is that approximately 75% of the budgeted costs are fixed, 15% depend on the number of productions staged, and the remaining 10% depend on the number of performances. After the beginning of the year, the board of directors of the theater authorized changing the theater’s program to four productions and a total of 64 performances. Actual costs were higher than the costs from the planning budget. (Grants from donors and ticket sales were also correspondingly higher, but are not shown here.) Data concerning the actual costs appear below: Programmazione e controllo - managerial accounting per le decisioni aziendali 3/ed Ray H. Garrison, Eric W. Noreen, Peter C. Brewer, Marco Agliati, Lino Cinquini © 2012, McGraw-Hill Required: 1. Prepare a flexible budget for The Munchkin Theater based on the actual activity of the year. 2. Prepare a flexible budget performance report for the year that shows both activity variances and spending variances. 3. If you were on the board of directors of the theater, would you be pleased with how well costs were controlled during the year? Why or why not? 4. The cost formulas provide figures for the average cost per production and average cost per performance. How accurate do you think these figures would be for predicting the cost of a new production or of an additional performance of a particular production?