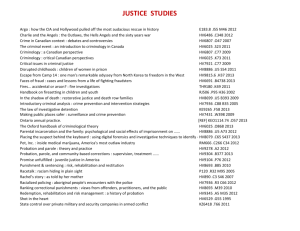

Assessing the Effectiveness of Organized Crime Control Strategies

advertisement