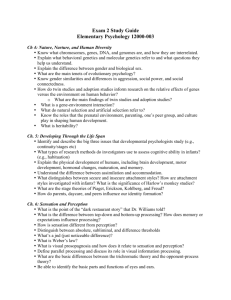

Perception and Attention - University of British Columbia

advertisement