impact of students' prior knowledge on learning

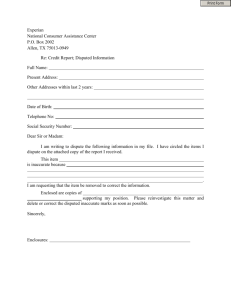

advertisement

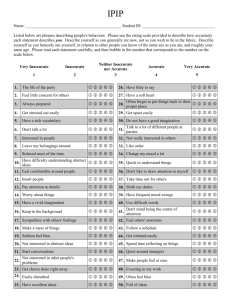

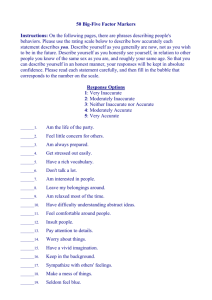

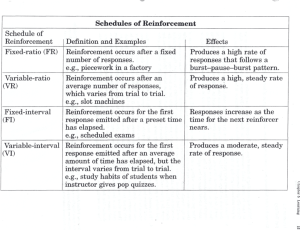

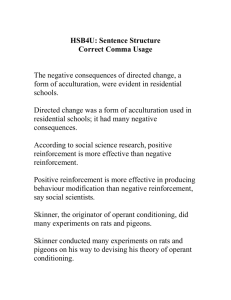

CENTER FOR TEACHING EXCELLENCE . UTPA IMPACT OF STUDENTS’ PRIOR KNOWLEDGE ON LEARNING T E A C H O U R R E S E A R C H A N D R E S E A R C H O U R T E A C H I N G DEBBIE COLE VALERIE TERRY JACOB NEUMANN COLIN CHARLTON WELCOME :-) 1. GET YOUR FOOD 2. MEET YOUR COLLEAGUES 3. FINISH YOUR SELFASSESSMENT THE NEW CTE WORKSHOPS • We designed materials for you to prepare beforehand. • We designed more interactive workshops with information and activities. • We want you to have a takeaway -> an immediately useful teaching product. • We will get your feedback later through a Qualtrics survey. HOW LEARNING WORKS SEVEN RESEARCH-BASED PRINCIPLES FOR SMART TEACHING • Today’s workshop is built out of How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching (Ambrose, et al.) • How Learning Works is our CTE BOOK CLUB selection -> Sign up today at www.utpa.edu/cte; this is our last call for participants! • What will you find in How Learning Works? HOW LEARNING WORKS SEVEN RESEARCH-BASED PRINCIPLES FOR SMART TEACHING But they said they knew this! I recently taught Research Methods in Decision Sciences for the first time. On the first day of class, I asked my students what kinds of statistical tests they had learned in the introductory statistics course that is a prerequisite for my course. Given what they told me, I was pretty confident that my first assignment was pitched at the appropriate level. It seemed pretty basic, but I was shocked at the way they handled it. Some students chose a completely inappropriate test while others chose the right test but did not have the foggiest idea how to apply it. Still others could not not interpret the results. What I can’t figure out is why they told me they knew this stuff when it’s clear from their work that most of them don’t have a clue. —Professor Soo Yon Won (10) HOW LEARNING WORKS SEVEN RESEARCH-BASED PRINCIPLES FOR SMART TEACHING Why is this so hard for them to understand? Every year in my introductory psychology class I teach my students about classic learning theory, particularly the concepts of positive and negative reinforcement. I know that these can be tough concepts for students to grasp, so I spell out very clearly that reinforcement always refers to increasing a behavior and punishment always refers to decreasing a behavior. I also emphasize that, contrary to what they might assume, negative reinforcement, does not mean punishment; it means removing something aversive to increase a desired behavior. But it seems that no matter how much I explain the concept, students continue to think of negative reinforcement as punishment. In fact, when I asked about negative reinforcement on a recent exam, almost 60 percent of the class got it wrong. Why is this so hard for students to understand? —Professor Anatole Dione (11) TODAY’S OVERVIEW • Table Discussion on Self-Assessment • Overview of Prior Knowledge Research & Practical Ideas (orange) • Planning Worksheet (yellow) • Large Group Discussion TABLE DISCUSSION Share your self assessment with the people at your table. • What surprised you? • What did you learn? • What do you want to do now? 4 STUDENTS’ PRIOR KNOWLEDGE RESEARCH & PRACTICAL IDEAS • Activating Prior Knowledge • Accurate But Insufficient Prior Knowledge • Inappropriate Prior Knowledge • Inaccurate Prior Knowledge ACTIVATING PRIOR KNOWLEDGE RESEARCH says… • Connecting prior to new knowledge helps new knowledge “stick” • Activating prior knowledge isn’t necessarily spontaneous • Asking trigger or elaboration questions helps recall (Tell me why…) • Asking students to generate knowledge from previous courses or personal experiences helps integration of new knowledge ACTIVATING PRIOR KNOWLEDGE A PRACTICAL STRATEGY is…SCAFFOLDING. • Explicitly Link New Material to Knowledge from Previous Courses: Ask students to specifically write about how their last paper/project in an intro class connects to the first chapter in a supplemental class. • Use Analogies and Examples That Connect to Students’ Everyday Knowledge: Ask students to explain how a new concept works in an everyday situation, like comparing cooking and lab science. ACCURATE BUT INSUFFICIENT PRIOR KNOWLEDGE RESEARCH says… • Some relevant knowledge does not ensure subsequent learning. • Declarative knowledge (of facts/concepts) is different from procedural knowledge (application/procedure). • Students can know concepts and fail application; students can perform accurate processes without articulating what they do or why. ACCURATE BUT INSUFFICIENT PRIOR KNOWLEDGE A PRACTICAL STRATEGY is…SHOWING THE KNOWING. • Identify for your students if you are asking them to know what, know how, or know when: In syllabi descriptions of outcomes and/or assignments, identify whether you’re asking for (and evaluating) concepts, procedures, applications, or combinations. INAPPROPRIATE PRIOR KNOWLEDGE Research says… • The misapplication of accurate prior knowledge in a new learning context can hinder student learning. • Faculty can help students avoid this by explicitly teaching the conditions and contexts in which prior knowledge is (in)applicable and deliberately activating relevant prior knowledge. INAPPROPRIATE PRIOR KNOWLEDGE PRACTICAL STRATEGIES are…EXPLAINING THE CONTEXTS OF THE RULES. • Provide students with “rules of thumb” to help them avoid common misapplications: “When you see ‘negative’ in the context of negative reinforcement, think of subtraction.” • Explicitly identify discipline-specific conventions: “Lab reports are written without the use of ‘I’ and procedures are described in the passive voice.” • Show students where analogies breakdown: “Neighborhood associations in Indonesia are like insurance companies in the United States, but nobody’s making a profit.” INACCURATE PRIOR KNOWLEDGE Research says… • Inaccurate prior knowledge distorts new knowledge because we strive for consistency. • Isolated ideas can be corrected with explicit refutation and evidence. • Misconceptions are integrated and stubborn. INACCURATE PRIOR KNOWLEDGE A PRACTICAL STRATEGY is…TESTING & TEACHING THE LONG GAME. • Ask students to make and test predictions: physics and testing how forces act on stationary and moving objects. • Ask students to justify their reasoning: pointing out internal contradictions in student summary of an writer’s argument. • Provide multiple and linked opportunities for testing. • Undoing inaccurate knowledge is critical thinking, and critical thinking takes time: Build more time into syllabi for recurring areas of inaccurate knowledge. MAKE A PLAN (YELLOW) • Describe an assignment or topic that usually works well in one of your classes. • Describe an assignment or topic that often doesn’t work well in one of your classes. • Map out a plan for working with students’ prior knowledge. FINAL THOUGHTS How will our work with students’ prior knowledge today affect what you do the next time you walk into your classroom? LOOKING BACK LOOKING FORWARD • We’ve self-assessed and discussed our understanding of students’ prior knowledge. • We reviewed research and practical ideas related to four different types of prior knowledge. • You made a plan for taking ideas and strategies from this workshop forward into your classroom. • And don’t forget — we want your feedback on our new workshop design. Please keep a look out for our Qualtrics survey. CENTER FOR TEACHING EXCELLENCE . UTPA IMPACT OF STUDENTS’ PRIOR KNOWLEDGE ON LEARNING T E A C H O U R R E S E A R C H A N D R E S E A R C H O U R T E A C H I N G DEBBIE COLE VALERIE TERRY JACOB NEUMANN COLIN CHARLTON