Organizational Change - Manajemen Files Narotama

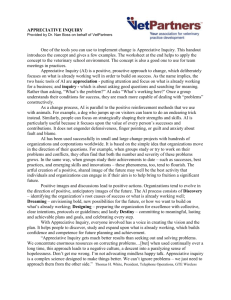

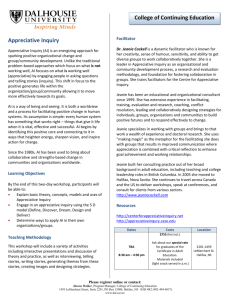

advertisement