EDUCATION, INDIGENOUS SURVIVAL and WELL

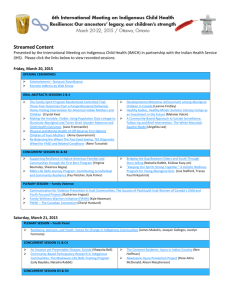

advertisement