A KANSAS TEEN IS HOPING TO PARTICIPATE IN AN

advertisement

HEALTH

By Kirsten Weir

A KANSAS TEEN IS HOPING TO PARTICIPATE IN AN

EXPERIMENTAL THERAPy THAT MIGHT SAVE HIS LIFE.

K

yle Hicks is a typical high school junior in

many ways. The 17-year-oldft-omWichita,

Kan., plays video games and loves chocolate and mac 'n' cheese. He hopes to go to

college and study meteorology.

But Kyle's life has been far from typical. Since birth,

he has suffered from a painftjl and eventually fatal skin

disease. "I didn't really think there would be a cure

for the disease in my lifetime," Kyle says. Now he

has reason to think there will. Researchers at the

University of Minnesota (UM) are testing a promising

new treatment for the disease.

MISSING PROTEIN

Kyle has epidermolysis bullosa (EB), a rare, inherited

condition. The form of EB that Kyle has, recessive

dystrophic EB,, is the most severe. His body cannot

make a protein called collagen type VU. "Its function

is to make anchors between the upper layer of skin and

deeper layers of skin," says Jakub Tolar, a member

of the UM research team. Collagen type VII holds

the skin together "like Velero," he says. Without it,

the skin blisters and sloughs off at the slightest touch.

Kyle suffers from painftil blisters and open wounds

all over his body. Each day, he wraps himself in gauze

and bandages to ward off deadly infections. The

frequent wounds have caused scar tissue to build up,

fusing his fingers together.

The disease also causes scar tissue to form in the

stomach and the esophagus, the muscular tube that

leads from the mouth to the stomach. That scarring

prevents Kyle from absorbing the nutrients he needs

to grow. At 17, he's only 1.2 meters (4 feet) tall and

weighs just over 23 kilograms {50 pounds).

The constant skin damage eventually

causes an aggressive type of skin cancer.

Few people with recessive dystrophic EB

live beyond 30. "It's painful and stressllil," Kyle says.

Kyte Hicks looks younger than 17 because his

ondftion robs him of nutrients. He wraps himself

1 bandages because the condition makes his

tcin vulnerable to iniury and infection.

6

October 17, 2008 CURRENT SCIENCE

STEM CELL

TRANSPLANT

Reading about his disease online

recently, Kyle came across an article

about UM's experimental treatment.

He e-mailed John Wagner, one of the

UM doctors, to say he wanted in.

Wagner, Tolar, and their colleagues

have spent several years searching

for a treatment for EB. Replacing

the missing protein, the researchers

reason, might cure the disease. They

began by experimenting on mice that

lacked collagen type VII, hoping that

an adull siem cell transplant might

hold the cure. Adult stem cells are

immature cells found in some tissues

that can mature and become many,

though not all, types of cells. After

much trial and error, Tolar discovered that stem cells in bone marrow

could supply the missing protein to

the sick mice. Bone marrow is the

soft, spongy tissue inside bones. It

contains adult stem cells that mature

into blood and immune system cells.

After receiving bone marrow transplants from healthy mice, some of

the EB mice got better.

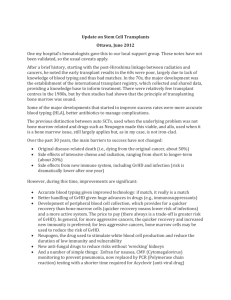

L o s t A n c h o r Kyle Hicks's skin cannot make a protein that anchors the

epidermlsto the dermis. The epidermis is the body's protective armor. It has an

underlying layer of cells that are always dividing and pushing the newly made

cells to the surface. As the new cells move outward, they break down; fill with

a tough, waterproof protein called keratin: and die. The dermis contains only living

cells, including hair follicles, sweat glands, and blood vessels.

hair shaft

sensory nerve

After that breakthrough, the team

decided to test the treatment in

humans. Last fall, the researchers

performed a bone marrow transplant

on Nate Liao, a 2-year-old with EB.

They took bone marrow from Nate's

healthy brother, whose tissues matched Nate's.

Gradually, Nate's skin showed signs of healing. After a

few months, tests showed his body was making collagen

type VII for the first time. Some of the transplanted

stem cells seemed to have made their way to his skin,

where they matured and started pumping out the

missing protein. "I have watched Nate improve every

day," his mother, Theresa Liao, told the Los Angeles

Times in June.

RISKy PROCEDURE

Bone marrow transplants are not without risks. All

transplant patients must take powerful drugs to kill

oft"their own immune cells; otherwise, those cells

would attack and destroy the transplanted tissue. "Not

everybody is able to live tlirough the transplant," Tolar

says. Patients who do survive can end up with organ

damage, hormonal problems, and an increased risk

of developing cancer. But for people with EB and

other deadly diseases, the hope of a cure might well

be worth the risk.

hairfoilicis

epidermis

dermis

hypodermis

(fatty tissue)

muscle

fat cells

sweat gland

blood vessel

It's too soon to say with certainty that bone marrow

transplants can cure EB, Tolar cautions. Yet he's

optimistic. "We expect this to be a lifelong source of

cells that can express collagen type VII, but we don't

know for sure," he says. He and his colleagues plan

to perform several more bone marrow transplants on

EB patients over the next two years. Then, they'll know

better how successiul the treatment is.

Kyle hopes to be one of the test subjects. "I instantly

wanted to do it," he says. He's found a donor whose

bone marrow matches his ovra and is trying to raise

money to pay for the procedure. So far, his insurance

company refuses to pay for the $500,000 operation,

but Kyle is trying to change the company's mind. "I

could get better, mayhe even before I get out of high

school," he says. "I'm anxious and excited and ready

to do it anytime " CS

C o n t a c t i n g K y l e You can contact Kyle and read mors

ahout his story on his personal hlog: www.cotaforkyleh.com. I

\

CURRENT SCIENCE October 17, 2008 7

I