Word template - green A4 portrait

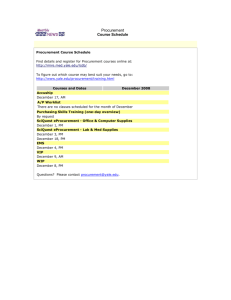

advertisement