Physica B 406 (2011) 84–87

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Physica B

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/physb

A computational study of silicon-doped aluminum phosphide nanotubes

Maryam Mirzaei a, Azadeh Aezami b, Mahmoud Mirzaei c,n

a

b

c

Department of Electrical Engineering, Islamic Azad University, South Tehran Branch, Tehran, Iran

Department of Physics, Islamic Azad University, Khuzestan Science and Research Branch, Ahvaz, Iran

Young Researchers Club, Islamic Azad University, Shahr-e-Rey Branch, Shahr-e-Rey, Iran

a r t i c l e i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Received 14 July 2010

Received in revised form

1 October 2010

Accepted 13 October 2010

We performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to investigate the properties of silicon-doped

(Si-doped) models of representative (4,4) armchair and (6,0) zigzag aluminum phosphide nanotubes

(AlPNTs). The structures were allowed to relax and the chemical shielding (CS) parameters were

calculated for the atoms of optimized structures. The results indicated that the band gap energies and

dipole moments detect the effects of dopant. The CS parameters also indicated that the Al and P atoms

close to the Si-doped region are such reactive atoms, which make the Si-doped AlPNTs more reactive than

the pristine AlPNTs. Moreover, replacement of P atom by the Si atom makes AlPNT more reactive than the

replacement of Al atom by the Si atom.

& 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Silicon doping

Aluminum phosphide nanotube

Electronic structure

Density functional theory

1. Introduction

Soon after the discovery of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [1],

considerable efforts have been dedicated on the investigations of

non-carbon nanotubes among which the counterparts of third and

fifth groups of elements are proposed as proper alternative

materials [2,3]. In contrast to the CNTs, which are metallic or

semiconductor depending on the tubular diameter and chirality,

the counterparts of third and fifth groups of elements are always

viewed as semiconductors independent of any restricting factors

[4,5]. To this time, numerous experimental and computational

studies have been devoted to characterize the properties of boron

nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) and aluminum nitride nanotubes

(AlNNTs) [6–10]. However, the properties of the tubular

structures of other III–V counterparts such as boron phosphide

(BP) and aluminum phosphide (AlP) have not been investigated

much [11,12]. In a recent study, we have investigated the

properties of representative models of armchair and zigzag

AlPNTs by computations of chemical shielding (CS) parameters

[12]. In another study, we have also indicated that the CS

parameters of BPNTs could detect well the effects of impurities

such as carbon atom [11].

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a versatile

technique to investigate the electronic and structural properties of

matters [13]. The CS parameters are very sensitive to the electronic

sites of atoms and could detect any effects on these sites. Earlier

n

Corresponding author. Fax: + 98 919 4709484.

E-mail address: mdmirzaei@yahoo.com (M. Mirzaei).

0921-4526/$ - see front matter & 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.physb.2010.10.026

studies indicated that the properties of nanotubes could be

investigated well by computations of the CS parameters [14,15].

Based on this efficiency, we have investigated the properties of

silicon-doped (Si-doped) models of representative armchair and

zigzag AlPNTs by quantum calculations of the CS parameters for the

optimized structures. Previous studies indicated that the Si-doped

CNTs and BNNTs contribute to physical and chemical interactions

with other atoms or molecules better than the pristine nanotubes

[16,17]. Moreover, the Si-doped nanotubes are viewed as reactive

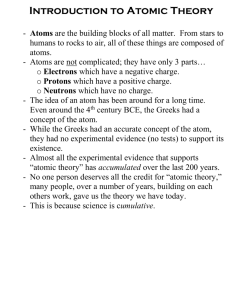

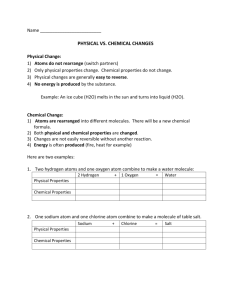

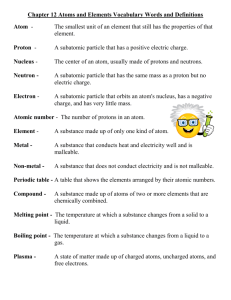

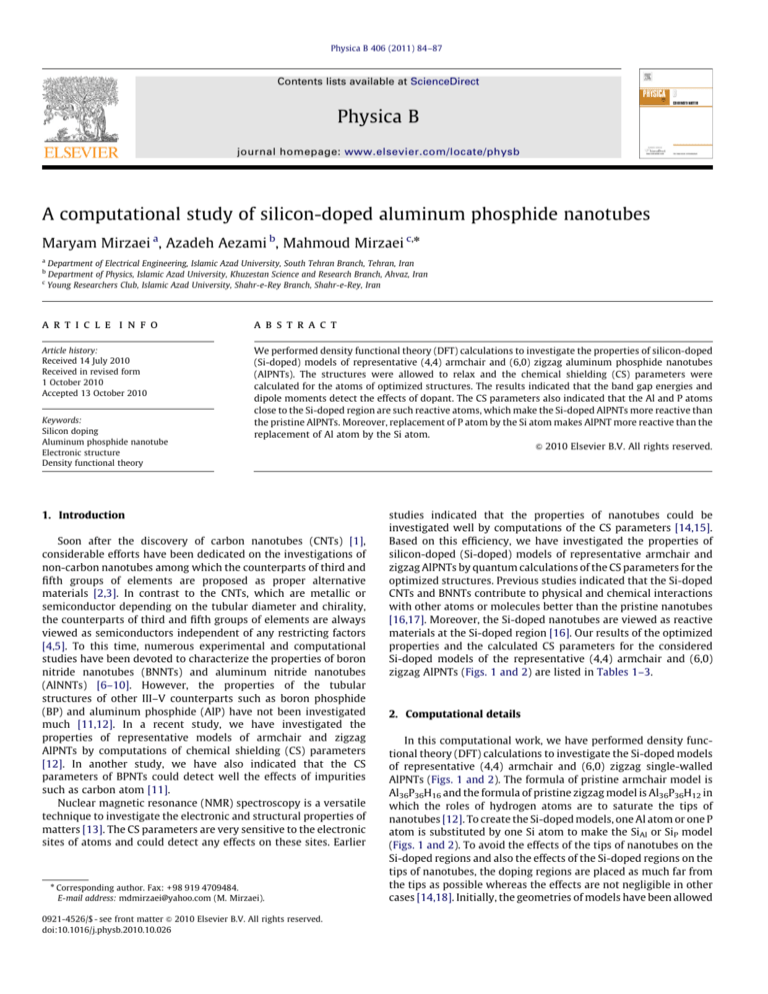

materials at the Si-doped region [16]. Our results of the optimized

properties and the calculated CS parameters for the considered

Si-doped models of the representative (4,4) armchair and (6,0)

zigzag AlPNTs (Figs. 1 and 2) are listed in Tables 1–3.

2. Computational details

In this computational work, we have performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to investigate the Si-doped models

of representative (4,4) armchair and (6,0) zigzag single-walled

AlPNTs (Figs. 1 and 2). The formula of pristine armchair model is

Al36P36H16 and the formula of pristine zigzag model is Al36P36H12 in

which the roles of hydrogen atoms are to saturate the tips of

nanotubes [12]. To create the Si-doped models, one Al atom or one P

atom is substituted by one Si atom to make the SiAl or SiP model

(Figs. 1 and 2). To avoid the effects of the tips of nanotubes on the

Si-doped regions and also the effects of the Si-doped regions on the

tips of nanotubes, the doping regions are placed as much far from

the tips as possible whereas the effects are not negligible in other

cases [14,18]. Initially, the geometries of models have been allowed

M. Mirzaei et al. / Physica B 406 (2011) 84–87

85

Table 1

Optimized structural propertiesa.

Property

Armchair models

EG (eV)

DM (Debye)

dAl P (Å)

Zigzag models

SiAl

SiP

Pristine

SiAl

SiP

Pristine

2.05

0.34

2.31

1.87

1.11

2.31

3.87

0.00

2.31

1.60

7.00

2.31

1.87

6.70

2.31

3.03

6.93

2.31

dAl Si (Å)

–

2.40

–

–

2.40

–

dSi P (Å)

2.27

–

–

2.27

–

–

dAl H (Å)

1.59

1.59

1.58

1.58

1.58

1.58

dP H (Å)

1.42

1.42

1.42

1.42

1.42

1.42

dTip (Å)

8.52

8.52

8.52

–

–

–

dAl-tip (Å)

–

–

–

7.00

7.00

7.00

dP-tip (Å)

–

–

–

8.10

8.10

8.10

a

See Figs. 1 and 2. For distances (d), the averaged values are reported. For

pristine model, the values are from Ref. [12].

Table 2

CS parameters for the

Fig. 1. 2D views of the Si-doped structures of the (4,4) AlPNT: SiAl (a) and SiP (b).

27

Al atom

27

Armchair models

SiP

SiAl

Al1

Al2

Al21

Al3

Al31

Al32

Al4

Al41

Al5

Al51

Al52

Al6

Al atomsa.

332;

337;

–

354;

350;

–

354;

360;

354;

276;

–

–

134

88

74

86

77

104

75

122

332;

337;

–

357;

360;

–

352;

346;

353;

336;

–

–

135

86

69

63

78

111

75

92

Zigzag models

Pristine

SiAl

332;

337;

–

356;

–

–

353;

–

356;

–

–

–

345;

342;

340;

345;

344;

344;

352;

286;

350;

356;

356;

315;

134

88

70

67

69

SiP

120

77

80

86

96

96

71

123

70

64

64

132

345;

342;

345;

341;

329;

329;

349;

347;

346;

346;

346;

314;

Pristine

121

75

75

96

124

124

83

117

74

71

71

132

345;

342;

–

347;

–

–

346;

—

346;

—

—

314;

120

78

82

79

74

133

a

See Figs. 1 and 2. The properties are in ppm. The first value of each row is for

isotropic chemical shielding and the second value is for anisotropic chemical

shielding. The underlined values are for 29Si atoms. For pristine model, the values are

from Ref. [12].

Table 3

CS parameters for the

31

P atom

Fig. 2. 2D views of the Si-doped structures of the (6,0) AlPNT: SiAl (a) and SiP (b).

to relax by all atomic optimizations using B3LYP exchangefunctional and 6-31G* standard basis set. Subsequently, at the

same DFT level, the CS parameters for the 27Al, 31P and 29Si atoms of

the optimized structures have been calculated based on the gaugeincluded atomic orbital (GIAO) approach [19]. The quantum

calculations yield the CS tensors (sii) in the principal axes

system (PAS) in which the orders of their eigenvalues are

s33 4 s22 4 s11 [13]. Therefore, directly relating to the

experimentally NMR measurements, the calculated CS tensors

are converted to the absolute values of isotropic CS (CSI) and

anisotropic CS (CSA) parameters using Eqs. (1) and (2) [13]. The

optimized properties and the calculated CS parameters for the

Si-doped models of (4,4) and (6,0) AlPNTs (Figs. 1 and 2) are shown

P atomsa.

Armchair models

SiP

SiAl

P2

P21

P3

P31

P32

P4

P41

P5

P51

P52

P6

31

503;

–

521;

525;

–

500;

452;

490;

415;

–

–

176

127

156

100

79

125

145

502;

–

522;

518;

–

502;

493;

509;

161;

–

–

175

124

146

120

130

105

484

Zigzag models

Pristine

SiAl

504;

–

524;

–

–

512;

–

513;

–

–

–

500;

498;

470;

433;

433;

473;

388;

487;

491;

491;

488;

179

116

110

106

SiP

168

169

135

163

163

133

149

124

130

130

194

501;

497;

479;

474;

474;

482;

139;

485;

487;

487;

487;

Pristine

165

158

129

148

148

135

495

130

151

151

190

501;

–

486;

–

–

489;

–

485;

–

–

488;

167

124

125

120

193

a

See Figs. 1 and 2. The properties are in ppm. The first value of each row is for

isotropic chemical shielding and the second value is for anisotropic chemical

shielding. The underlined values are for 29Si atoms. For pristine model, the values are

from Ref. [12].

in Tables 1–3. All calculations are performed by the Gaussian 98

package [20].

1

CSI ðppmÞ ¼ ðs33 þ s22 þ s11 Þ

3

ð1Þ

86

M. Mirzaei et al. / Physica B 406 (2011) 84–87

1

CSA ðppmÞ ¼ s33 - ðs22 þ s11 Þ; ðs33 4 s22 4 s11 Þ

2

ð2Þ

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Investigated structures

Our investigated structures consist of the Si-doped models of

representative (4,4) armchair and (6,0) zigzag AlPNTs in which one Al

atom is replaced by one Si atom in the SiAl models (Figs. 1a and 2a)

whereas one P atom is replaced by one Si atom in the SiP models

(Figs. 1b and 2b). Table 1 shows the optimized structural properties of

the Si-doped models of this study and the pristine models

from an earlier study [12]. In comparison to the pristine 3model,

the values of band gap energies (EG) are decreased in the Si-doped

models. The SiAl models could be considered as n-type semiconductors and the SiP models could be considered as p-type

semiconductors because the number of electrons in valence shell

of the Si atom is more than that of the Al atom but it is fewer

compared to the P atom. Therefore, the changes in the values of EG are

reasonable for the Si-doped models of AlPNTs. The armchair AlPNT

has two similar tubular tips but the zigzag AlPNT has two different

tips of Al- and P-tip. Therefore, the value of dipole moment (DM) for

the pristine armchair model is zero but the value of DM for the pristine

zigzag AlPNT is not zero due to the situations of tubular tips.

Interestingly, the values of DM for the Si-doped models of armchair

AlPNTs are not zero and the values of DM for the Si-doped models of

zigzag AlPNTs are changed. There are Si P bonds in addition to the

initial AlP, Al H and PH bonds in the SiAl model and there are

Al Si bonds in addition to the initial Al P, Al H and P H bonds in

the SiP model. Although different types of bonds exist in the Si-doped

models, but the averaged values of the bond distances and also the tip

diameters do not detect any changes in comparison to the pristine

models. This trend could approve the traceless concentration of the Si

atom in the Si-doped models in which the bond distances and the tip

diameters do not detect the effects of dopant.

3.2. CS parameters for the

27

Al atoms

Table 2 shows the calculated isotropic and anisotropic chemical

shielding (CSI and CSA) parameters for the 27Al atoms of the pristine

and Si-doped models of armchair and zigzag AlPNTs. An earlier

study [12] indicated that the CS parameters for the 27Al atoms of the

pristine model could be divided into layers based on the similarities

of values for atoms of each layer. Al1 stands for the Al atoms at the

tips of nanotubes in which the values of CS parameters for Al1

atoms are similar for the Si-doped and pristine models of the

armchair and zigzag AlPNTs. This trend reveals that the Al atoms at

the tips of nanotube do not detect the effects of traceless

concentration of dopant. In the armchair SiAl AlPNT, where Al51

is replaced by the Si atom, the values of CS parameters for Al31 and

Al41 atoms detect the effects of dopant. According to the Eqs. (1)

and (2), it is important to note that the CSI parameter means the

averaged values of electronic densities at the atomic sites but

the CSA parameter means the difference between the orientation of

the electronic densities perpendicular to the molecular plane

(z axis) and the orientation of the electronic densities in the

molecular plane (x–y axes). Indeed, the s22 and s11 eigenvalues

belong to the orientations of the CS tensors in the molecular plane

but the s33 eigenvalue belongs to the orientations of the CS tensors

perpendicular to the molecular plane. In earlier studies, we have

indicated that the electronic properties of the doped nanotubes

could be detected well by computing the CS properties in the

doped and pristine models [14,21,22]. However, if an interested

researcher would like to exhibit the exact contributions of the

atomic orbitals, performing natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis

could be a proper tool for the purpose [23] but it is not the purpose

of this study. Indeed the CS parameters indicate the overall

electronic contributions of the atoms to the doped regions and

we have employed these parameters to interpret the Si-doped

models of the AlPNTs. In comparison to the pristine model, the

changes in the values of CSA parameters for Al31 and Al41 atoms are

more significant than the changes in the values of their CSI

parameters, which mean that the total electronic density almost

remained unchanged but the orientation in the molecular frame is

changed.

In the zigzag SiAl AlPNT, where A41 is replaced by the Si atom,

similar results are found for the values of CS parameters for Al31 and

Al32 atoms. Moreover, the CS parameters for Al51 and Al52 also

detect the effects of dopant in which the value of CSI parameters are

increased whereas the values of CSA parameters are decreased in

comparison to the pristine model. The changes in the CS parameters for other Al atoms are almost negligible. In the armchair SiP

model, due to the replacement of P51 by the Si atom, three Al Si

bonds are resulted instead of the initial three Al P bonds. The CS

parameters for Al31 detect slight changes but the most significant

changes in the CS parameters are observed for Al41 and Al51 atoms

that are in chemical bonding with the Si atom. The reductions in CSI

values and the increments in the CSA values for these two Al atoms

indicate that the tendency of these atoms for contribution to Al Si

bonds is less than the tendency for contributions to the Al P

bonds. For the zigzag SiP model, similar results are found for Al31,

Al32 and Al41 atoms that are directly bonded to the Si atom. Parallel

to the previous trend about the more reactivity of the Si-doped

nanotubes than the pristine nanotubes [16], our results also

indicate that the Si-doped AlPNTs could be more reactive than

the pristine AlPNTs because of larger values of CSA parameters for

Al atoms at the Si-doped regions.

3.3. CS parameters for the

31

P atoms

The calculated CSI and CSA parameters for 31P atoms of the SiAl

and SiP models of (4,4) armchair and (6,0) zigzag AlPNTs (Figs. 1b

and 2b) are listed in Table 3. According to the earlier study on

pristine AlPNTs [12], the CS parameters for 31P atoms of the pristine

AlPNT are divided into layers based on similarities in the values for

atoms of each layer. The values for P1 atoms of the Si-doped and

pristine models do not show any difference, which implies that the

electronic properties of the P atoms at the tips of Si-doped

nanotubes do not detect the effects of dopant. In the armchair

SiAl AlPNT, Al51 atom is replaced by the P atom; therefore, three

Si P bonds are resulted instead of three Al P bonds. Although

both of P41 and P51 atoms are chemically bonded to the Si atom, but

the electronic properties of these two atoms detect different effects

of the Si-doped region. By the optimization process, the

geometrical position of P51 is relaxed inwardly but the initial

status of geometrical position of P41 remained unchanged. Due to

the different geometrical positions, the calculated CS parameters

are different for P41 and P51 atoms of the SiAl model. The electronic

distribution of P41 atom is remarkably oriented in the molecular

plane whereas the electronic distribution of P51 atom is remarkably

oriented perpendicular to the molecular plane as indicated by the

smaller value of CSA parameter for P41 atom and the larger value of

CSA parameter for P51 atom. The CSA parameter for P31 atom of the

SiAl model also detects the effects of Si doping in which the

electronic distribution for this atom is oriented perpendicular to

the molecular plane.

In the armchair SiP AlPNT, P51 is replaced by the Si atom,

resulting three Al Si bonds instead of three Al P bonds. The P

M. Mirzaei et al. / Physica B 406 (2011) 84–87

atoms are not chemically bonded to the Si atom, but the CS

parameters for the P atoms detect the effects of the Si-doped

region. The CS parameters for P31 and P41 atoms, which are close to

the Si-doped region, detect the effects of Si doping as could be seen

by decreasing the value of CSI parameter and increasing the value of

CSA parameter. In the zigzag SiAl AlPNT, replacement of Al41 by the

Si atom results in three Si P bonds where P31, P32 and P41 are

chemically bonded to the Si atom. In comparison to the results of

the pristine zigzag AlPNT, the CS parameters for the mentioned

P atoms are changed due to the Si doping. Moreover, the results

indicate that the tendency of P atom for contribution to the

Si P bond is less than the tendency for contribution to the

Al P bond. In the SiP zigzag AlPNT, where P41 is replaced by Si

atom, the P atoms are not in direct chemical bonding to the Si atom

but their CS parameters detect the effects of the Si-doped region.

The CS parameters for P31, P32, P51 and P52 atoms detect the most

significant changes in comparison to the pristine model. The results

indicate that the averaged electronic densities at these atomic sites

are not changed; however, the electronic distributions are remarkably oriented perpendicular to the molecular plane. Parallel to the

results for Al atoms of the Si-doped AlPNTs, the results for the P

atoms also indicate that the Si-doped AlPNTs are more reactive

than the pristine AlPNTs, which are in agreement with the previous

trend about the Si-doped nanotubes [16].

3.4. CS parameters for the

29

Si atoms

CS parameters for the 29Si atoms, which are underlined in

Tables 2 and 3, indicate that the orientations of the electronic

distributions of Si atoms of the SiAl models are more oriented in the

molecular plane whereas these distributions of the SiP models are

more oriented perpendicular to the molecular plane. There are

three Si P bonds in the SiAl models of AlPNT and there are three

Al Si bonds in the SiP models. It is important to note that the

electronegativity of the Al atom is smaller than the P atom.

Moreover, the electronegativity of the Si atom is larger than that

of the Al atom but smaller than that of the P atom. According to the

order of the values of electronegativities, P4Si 4Al, the Al atom of

the SiAl model is doped by the Si atom with a larger value of

electronegativity but the P atom of SiP model is doped by the Si

atom with a smaller value of electronegativity. Therefore, the initial

ionic properties of Al P bonds are changed in the new Al Si and

Si P bonds. The values of the CS parameters for the 29Si atoms

reveal that the initial properties of the Al P bonds are changed less

in the SiAl model than the SiP model. It could be concluded that the

SiP model is more reactive than the SiAl model because of more

changes in electronic properties of the SiP model than the SiAl

model. In these cases, it seems that Si doping of the Al atom is more

favorable than that of the P atom. In other words, the formations of

the Si P bonds in the SiAl model are preferred than the formations

of the Al Si bonds in the SiP model.

87

4. Concluding remarks

Our DFT calculated parameters indicated that the electronic and

structural properties of the (4,4) and (6,0) AlPNTs detect the effects

of Si-doped region. The optimized properties indicated that the

bond distances and tip diameters do not detect any effects, but

the values of band gap energies and dipole moments exhibit the

changes in the effects of Si-doped region. The CS parameters for the

atoms at the tips of nanotubes do not detect the effects of dopant,

but both Al and P atoms close to the Si-doped region detect

remarkable changes. The values of CS parameters for the Al and P

atoms close to the Si-doped region indicate that the Si-doped

AlPNTs are more reactive than the pristine AlPNTs. Moreover, this

reactivity for the SiP model, where the P atom is replaced by the Si

atom, is more remarkable than the SiAl model, where the Al atom is

replaced by the Si atom.

References

[1] S. Iijima, Nature 354 (1991) 56.

[2] X. Chen, J. Ma, Z. Hu, Q. Wu, Y. Chen, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (2005) 17144.

[3] A. Loiseau, F. Willaime, N. Demoncy, N. Schramcheko, G. Hug, C. Colliex,

H. Pascard, Carbon 36 (1998) 743.

[4] I. Vurgaftman, J.R. Meyer, J. Appl. Phys. 94 (2003) 3575.

[5] X. Balasé, A. Rubio, S.G. Louie, M.L. Cohen, Europhys. Lett. 28 (1994) 335.

[6] Q. Dong, X.M. Li, W.Q. Tian, X.R. Huang, C.C. Sun, J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem.) 948

(2010) 83.

[7] X.Y. Cui, B.S. Yang, H.S. Wu, J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem.) 941 (2010) 144.

[8] W.H. Moon, H.J. Hwang, Phys. Lett. A 320 (2004) 446.

[9] R. Thapa, B. Saha, N.S. Das, U.N. Maiti, K.K. Chattopadhyay, Appl. Surf. Sci. 256

(2010) 3988.

[10] L. Lai, W. Song, J. Lu, Z.X. Gao, S. Nagase, M. Ni, W.N. Mei, J.J. Liu, D.P. Yu, H.Q. Ye,

J. Phys. Chem. B 110 (2006) 14092.

[11] M. Mirzaei, J. Mol. Model. (2010), doi:10.1007/s00894-010-0702-z.

[12] M. Mirzaei, M. Mirzaei, J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem.) 951 (2010) 69.

[13] F.A. Bovey, in: Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy, Academic Press, San

Diego, 1988.

[14] M. Mirzaei, M. Mirzaei, J. Molec. Struct. (Theochem.) 953 (2010) 134.

[15] M. Mirzaei, Physica E 42 (2010) 1954.

[16] R. Wang, R. Zhu, D. Zhang, Chem. Phys. Lett. 467 (2008) 131.

[17] I. Zanella, S.B. Fagan, R. Mota, A. Fazzio, Chem. Phys. Lett. 439 (2007) 348.

[18] M. Mirzaei, M. Mirzaei, Physica E 42 (2010) 2147.

[19] K. Wolinski, J.F. Hinton, P. Pulay, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112 (1990) 8251.

[20] M.J. Frisch, G.W. Trucks, H.B. Schlegel, G.E. Scuseria, M.A. Robb, J.R. Cheeseman, V.G. Zakrzewski, J.A. Montgomery Jr., R.E. Stratmann, J.C. Burant,

S. Dapprich, J.M. Millam, A.D. Daniels, K.N. Kudin, M.C. Strain, O. Farkas,

J. Tomasi, V. Barone, M. Cossi, R. Cammi, B. Mennucci, C. Pomelli, C. Adamo,

S. Clifford, J. Ochterski, G.A. Petersson, P.Y. Ayala, Q. Cui, K. Morokuma,

D.K. Malick, A.D. Rabuck, K. Raghavachari, J.B. Foresman, J. Cioslowski,

J.V. Ortiz, A.G. Baboul, B.B. Stefanov, G. Liu, A. Liashenko, P. Piskorz,

I. Komaromi, R. Gomperts, R.L. Martin, D.J. Fox, T. Keith, M.A. Al-Laham,

C.Y. Peng, A. Nanayakkara, C. Gonzalez, M. Challacombe, P.M.W. Gill,

B. Johnson, W. Chen, M.W. Wong, J.L. Andres, C. Gonzalez, M. Head-Gordon,

E.S. Replogle, J.A. Pople, Gaussian, 98, Gaussian, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, 1998.

[21] M. Mirzaei, A. Seif, N.L. Hadipour, Chem. Phys. Lett. 461 (2008) 246.

[22] M. Mirzaei, Physica E 41 (2009) 883.

[23] S.P. Hernández-Rivera, R. Infante-Castillo, J. Molec. Struct. (Theochem.) (2010),

doi:10.1016/j.theochem.2010.08.022.