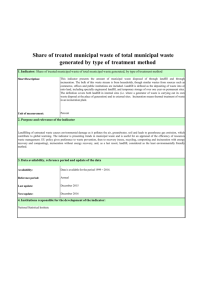

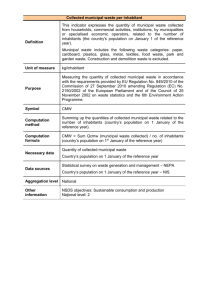

Waste management - Netherlands Polish Chamber of Commerce

advertisement