Student Self-Assessment

advertisement

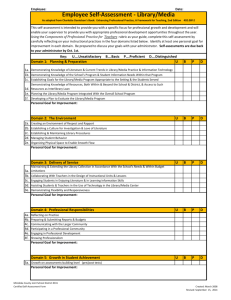

The Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat CAPACITY BUILDING SERIES The Capacity Building Series is produced by The Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat to support leadership and instructional effectiveness in Ontario schools. The series is posted at: www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/ literacynumeracy/inspire/ Why student self-assessment? “Self-assessment by pupils, far from being a luxury, is in fact an essential component of formative assessment. When anyone is trying to learn, feedback about the effort has three elements: recognition of the desired goal, evidence about present position, and some understanding of a way to close the gap between the two. All three must be understood to some degree by anyone before he or she can take action to improve learning … If formative assessment is to be productive, pupils should be trained in self-assessment so that they can understand the main purposes of their learning and thereby grasp what they need to do to achieve.” (Black & Wiliam, 1998, p. 143) STUDENT SELF-ASSESSMENT SECRETARIAT SPECIAL EDITION # 4 Assessment practices have started to change over the last several years with teachers building a larger repertoire of assessment tools and strategies. There is a greater understanding of the importance of timely assessments for learning as well as regular assessments of learning. One type of assessment that has been shown to raise students’ achievement significantly is student self-assessment (Black & William, 1998; Chappuis & Stiggins, 2002; Rolheiser & Ross, 2001; White & Frederiksen, 1998). Confidence and efficacy play a critical role in accurate and meaningful self-assessment and goal-setting. Rolheiser, Bower, and Stevahn (2000) argue that self-confidence influences “[the] learning goals that students set and the effort they devote to accomplishing those goals. An upward cycle of learning results when students confidently set learning goals that are moderately challenging yet realistic, and then exert the effort, energy, and resources needed to accomplish those goals” (p. 35). By explicitly teaching students how to set appropriate goals as well as how to assess their work realistically and accurately, teachers can help to promote this upward cycle of learning and self-confidence (Ross, 2006). Terminology of Assessment Clear and concise definitions of key terms help to ensure that everyone understands the nature of student self-assessment and its role in student achievement. Assessment is the process of “gathering information … from a variety of sources that accurately reflects how well a student is achieving the curriculum expectations in a subject” (Ministry of Education, 2006d, p. 15). December 2007 ISSN: 1913 8482 (Print) ISSN: 1913 8490 (Online) Student self-assessment is “the process by which the student gathers information about and reflects on his or her own learning … [it] is the student’s own assessment of personal progress in knowledge, skills, processes, or attitudes. Self-assessment leads a student to a greater awareness and understanding of himself or herself as a learner” (Ministry of Education, 2002, p. 3). Benefits for students • development of metacognitive skills – students become more skilled at adjusting what they are doing to improve the quality of their work (Cooper, 2006) • increased responsibility for students’ own learning as a result of more opportunities for self-reflection (Cyboran, 2006) • positive effects for low achievers – reducing achievement gaps (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Chappuis, & Stiggins, 2002) • development and refinement of students’ capacity for critical thinking (Cooper, 2006) • increased mathematics problem-solving ability (Brookhart, Andolina, Zuza, & Furman, 2004) • improved academic results in narrative writing (Ross, Rolheiser, & Hogaboam-Gray) • reduction in disruptive behaviour (Ross, 2006) Evaluation is an informed professional judgment about the quality of a child’s work at a point in time. This judgment is based on the student’s best, most consistent work or performance, utilizing established criteria. In kindergarten, evaluation is largely a description of what the teacher has observed in the classroom whereas, in Grades 1–8, it is tied to the levels of achievement described in the Ontario Curriculum documents (Ministry of Education, 2006d, p. 15). Reflection is an essential component of effective self-assessment; it occurs “when students think about how their work meets established criteria; they analyze the effectiveness of their efforts, and plan for improvement” (Rolheiser, Bower, & Stevahn, 2000, p. 31). Metacognition is “thinking about thinking” (Rolheiser, Bower, & Stevahn, 2000, p. 32). Developing reflective processes can lead to improved metacognition. Rolheiser and colleagues note that when students develop their capacity to understand their own thinking processes, they are better equipped to employ the necessary cognitive skills to complete a task or achieve a goal. They also note that “students who have acquired metacognitive skills are better able to compensate for both low ability and insufficient information” (p. 34). Developing reflective processes can lead to improved metacognition. Goal-setting is a key component of the self-assessment process, as well as a significant learning skill. In particular, setting goals “helps students who have negative orientations toward learning or who do not have realistic views of their strengths and weaknesses. Teachers can help these students by establishing appropriate goals, selecting effective learning strategies to reach those goals, committing effort toward those goals, and celebrating the results of their performances” (Rolheiser, Bower, & Stevahn, 2000, p. 77). Steps to Self-Assessment There are a number of steps that teachers can take to ensure that their students learn how to self-assess effectively (adapted from Rolheiser & Ross, 2001). Students and parents need to understand not only what self-assessment is, but also why and how it is being used to support student learning. Getting Started • Model/intentionally teach critical thinking skills required for self-assessment practices. • Address students’ perceptions of self-assessment, and engage students in discussions or activities focused on why self-assessment is important. • Anticipate that students will respond differently to opportunities for self-assessment; some may welcome them, while others may question their worth. • Allow time for learning self-assessment skills. • Provide students with many opportunities to practise different aspects of the selfassessment process as they gradually assume more responsibility for their own learning (e.g., brainstorming possible criteria for assessment, applying these criteria to their own work, receiving timely feedback on their self-assessments and developing goals and action plans). • Have students self-assess familiar tasks or performances using clearly identified criteria. • Ensure that parents/guardians understand that self-assessment is only one of a variety of assessment strategies that you use and why you use it. 2 The Process Dunning, Heath and Suls (2004) observe that “accurate self-assessment is … crucial for education to be a lifelong enterprise that continues far after the student has left the classroom” (p. 85), and Williams (as cited in Dunning et al., 2004) has found that “the ability to ‘know thyself’ can be assessed, trained, and improved, resulting in worthwhile increases in performance” (p. ii). Benefits for teachers • increase in student engagement (Bruce, 2001) Students need to learn how to assess their own progress by asking themselves some key questions about where they are in their learning: Where am I now? Where am I trying to go? What do I need to get there? How will I know I have accomplished what I set out to do? • students begin to internalize instructional goals and apply them to future efforts (Herbert, 1998) To help students determine where they are now, teachers can ... • ensure that students understand the criteria for quality work, so that they are able to assess themselves as fairly and accurately as possible • help students gradually assume more responsibility for their own learning, as they practise using self-assessment tools such as checklists, rubrics and student-led conferencing forms • provide students with opportunities to discuss their self-assessments in light of peer and teacher assessments • ensure that all stakeholders provide specific anecdotal feedback rather than scores or grades to identify explicit next steps for student learning Tip for teachers ... “Work with a peer or colleague in experimenting with self-assessment. Such experimentation will enhance personal assessment literacy. The constructive dissonance, social comparison, synthesis, and experimentation that occur when working with others will have a significant effect on your learning, and ultimately, on your students’ learning. Collaboration will help you more effectively link student learning and instructional approaches for the purpose of continuous improvement.” (Rolheiser & Ross, 2000, p. 36) To help students determine where they intend to go, teachers can ... • develop with students clearly articulated learning targets and provide concrete exemplars of student work; students need to understand what they’re “aiming for” • define good work using language that is meaningful for the learners; ideally, involve students in determining the language that is used • establish what language or symbols will be used for the purposes of reflection and self-assessment, depending on age level and development • model goal-setting for students • monitor the goals that students set for themselves (i.e., that they are meaningful and manageable) • ensure that goals are recorded for future reference • access to information, otherwise unavailable, about student effort and persistence (Rolheiser & Ross, 2000) To help students determine what they need to do to get there, teachers can ... • collaboratively identify strengths and gaps in student learning through the analysis of a variety of data • help students to develop realistic action plans that are practical and directly linked to the goals that have been selected • monitor students’ progress as they implement action plans To help students determine whether they have accomplished what they had set out to do, teachers can ... • have students revisit long-term goals periodically to reflect on their relevance and to make any necessary adjustments • talk with each student about his/her goal(s) • have students write a specific reflection about their goal(s) and what they did to achieve them – students may need guidance to identify their strengths and areas for improvement 3 Reflective questions for teachers ... • Is my assessment inclusive of all my students? • How can I share/co-create the criteria for assessment with my students? • How will my students demonstrate their understanding of the assessment process? • How will I involve my students in the assessment process? • How can I help students to understand how the assessment process helps them? • How can I provide opportunities for students to determine next steps for their learning? • How does this assessment build on my students’ metacognitive skills? (The Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat, 2006, p. 25) Communicating with Parents • Students benefit from self-assessment as part of routine practice. • Grades on report cards are determined by the teacher only, and are based on a range of assessments (e.g., projects, performance tasks, quizzes). • Teachers use a variety of assessment instruments – student self-assessment is part of a broader array of formative feedback that informs instruction. • The accuracy of students’ self-assessments has been shown to improve when they are taught how to self-assess in a systematic way (Rolheiser & Ross, 2001). School Leadership Support • Collect data about your school’s current assessment practices. • Have teachers complete a gap analysis survey regarding current use of student selfassessment (“Self-Assessment: A Growth Continuum for Teacher Reflection” on page 7 can be used for the purpose of gap analysis). • Conduct an audit of assessment tools used by teachers, and then develop a schoolwide assessment literacy plan with common assessments for various grades. • Facilitate the sharing of assessments where teachers come together and compare assessment tools and strategies. • Ask the question: Can your students articulate (to teachers, parents) their own strengths and areas for improvement needed in reading, writing and/or mathematics? • Build on the expertise of teachers in your school who are currently utilizing student self-assessment and have them share ideas through mentoring, coaching opportunities, divisional meetings or on a professional learning day. Making the Most of Student Self-Assessment Ross (2006) has summarized the research on the reliability, validity and utility of selfassessment. Below are the key findings of this research together with suggestions for how teachers can help make student self-assessment practices more effective and accurate. The outcome for teachers, according to Ross, is that it will contribute to higher student motivation, confidence and achievement. Do students self-assess accurately? Student self-assessments tend to be higher than assessments undertaken by the teacher. For example, young children may over-estimate “because they lack the cognitive skills to integrate information about their abilities and are more vulnerable to wishful thinking” (Ross, 2006, p. 3). Inflation is more likely to occur for older students if they believe that the self-assessments will directly affect their grades (see also Dunning, Heath & Suls, 2004, p. 88). Actions teachers can take ... • intentionally teach students how to self-assess using criteria and provide many opportunities to practise • involve students in jointly constructing rubrics, so that they may deepen their understanding of the criteria they are using to self-assess • ensure that students understand that self-assessments are formative, and help to improve their overall performance • create opportunities for learners to compare their self-assessments to those of their peers and teacher(s) • collect self-assessments at various times (i.e., not always immediately following instruction) 4 Do students’ self-assessments align with those of their peers and teachers? Evidence about validity is mixed; most studies base their conclusions on the correlation between student self-assessment scores and teacher-rated scores or peer appraisal. There are many possible reasons for the variation in self-teacher agreement, especially “student inability to apply assessment criteria, interest bias, and the unreliability of teacher assessments” (Ross, 2006, p. 4). However, the alignment of teacher and student assessments is “higher when students have been taught how to assess their work” (p. 3). Actions teachers can take ... • provide frequent opportunities for students to receive and use feedback over time • communicate to parents/guardians that the power of student self-assessment lies in its impact on student learning and achievement, as well as student confidence, motivation and engagement If student self-assessment cannot be used for grading purposes in Ontario, why should I devote class time to teaching my students how to do it? Self-assessment has been shown to impact both increased student achievement and improved student behaviour. Involvement in the classroom assessment processes can increase student engagement and motivation (Ross, 2006). Actions teachers can take ... • provide opportunities for students to discuss what is expected of them and to negotiate expectations for an assignment • understand that even though they are involving students in the assessment process, they are “not surrender[ing]control of assessment criteria”; rather they are setting up a process in which “students develop a deeper understanding of key expectations mandated by governing curriculum guidelines” (Ross, 2006, p. 8). How do I ensure that students who perceive themselves as unsuccessful do not assess themselves harshly and inaccurately? When students self-assess positively, they set higher goals for themselves and commit more personal resources or effort to them (Rolheiser, 1996). Students may self-judge and self-react to achievement results regardless of teacher input. “A stream of negative selfassessments can lead students to select personal goals that are unrealistic, adopt learning strategies which are ineffective, exert low effort and make excuses for performance” (Stipek, Recchia, & McClintic, 1992, cited in Ross, 2006, p. 7). “We can’t buy assessments that will circumvent teachers’ need for deeper assessment expertise. Off the shelf assessments may be marketed as formative assessments, but they don’t help teachers understand or apply the strategies that have been proven to increase student learning … They do not show teachers how to make learning targets clear to students or how to help students differentiate between strong and weak work … They do not help teachers show students how to assess their own strengths and weaknesses, nor do they emphasize the motivational power of having students track and share their learning. They cannot substitute for the professional development needed to cause changes in assessment practice in the classroom.” (Stiggins & Chapuis, 2006, p.13) Rethinking Classroom Assessment with Purpose in Mind In this webcast, Dr. Lorna Earl highlights three purposes of assessment – assessment as learning, assessment for learning and assessment of learning – and describes how they require different planning, use and reporting to promote student learning. View the webcast at: http://www.curriculum.org/secretariat/ april27.html Actions teachers can take ... • identify a focus and/or next steps based on identified gaps in student understanding • encourage students to focus on concrete data rather than past performances or patterns of achievement; self-assessing analytically versus holistically may assist with this process • when responding to students’ self-assessments, give feedback that motivates students to continue their learning; ask them what they think, what helped them, and how they deal with challenges; focus on the positive (Rolheiser et al.,2000, p. 65) 5 Tools and Strategies to Engage Students The ability to self-assess effectively develops over time and with experience (Cassidy, 2007). With this in mind, it is helpful for teachers to select tools and strategies that can be used in all divisions. The tools and strategies suggested below should be adapted by teachers to suit the various needs of their diverse student population. Teachers need time to learn these tools and strategies as they promote a shift away from quantitative to qualitative learning. Each allows for self-assessment of both process and product, and focuses on assessment for learning. Each demands that students revisit their own work, engage in reflection and set goals for improvement. CHECKLISTS Rubrics Suggestions for Getting Started • Start by developing checklists with students before moving on to rubric development, as checklists are easier to construct and use. • Use checklists when a process or product can be broken into components; they are quick and useful in situations involving a large number of criteria. • Align checklists closely with tasks. Suggestions for Getting Started • Rubrics are more powerful when used in conjunction with samples of student work or exemplars. • Consider ready-made rubrics only as starting points – constantly modify them with student input. • Consider having students assess a model piece of work using a rubric. • Use rubrics as guides during the writing process. • Create rubrics with students about a familiar topic, ensuring that you take into account various cultures, developmental stages and background experiences (e.g., an ideal birthday party, an excellent school, a great teacher, the best playground, a friend, classroom behaviour, etc.). • Work with students to put rubrics into student-friendly language. • Allow students to highlight or checkmark rubrics, using them as a visual guide while completing assignments. Resources: Cleland (1999); Ministry of Education (2005) (Appendices 3 & 6). “Tools for self-assessment may include surveys, interest inventories, checklists, reader’s notebooks, conferences, and sentence stems to guide reflection.” (Ministry of Education, 2006b, p. 27) EXEMPLARS Suggestions for Getting Started • Model/create an exemplar to support student understanding. • Display student-/teacher-generated exemplars in your classroom. • Use exemplars with accompanying rubrics. • Have students sort exemplars into levels according to a rubric and give reasons for their choices. • Have students compare their own work with exemplars. Resources: EQAO Exemplars. “You could make schools better if you show us what good work looks like and help us see what comes next.” (Booth, Green & Booth, 2004, p. 159) “One theme that emerges from our review is that the road to self-accuracy may involve information from or about other people … For example, in educational settings, benchmarking has been shown to improve self-evaluation accuracy” (Dunning et al., 2004, p. 99) Resources: Saddler & Andrade (2004). “Without careful instruction, rubrics can become the students’ destination rather than a road map for helping them reach that destination. Rubrics are tools designed to provide constructive feedback for students through self-, peer, or teacher assessment in order to further develop skills or knowledge.” (Creighton, 2000, p. 38) “Good rubrics embrace what we value most deeply ... a rubric demands reflecting on and describing performance with some precision; creating a rubric teaches us to think.” (Spandel, 2006, p. 16) AUDIO/VIDEO RECORDINGS Suggestions for Getting Started • Have students read orally into a digital voice recorder and reflect on their own fluency and use of cueing systems. • Video tape students during oral presentations. • Tape small group discussions. • Use a rubric or checklist for students to guide their selfassessments while viewing or listening. • Create audio/visual exemplars. Resources: Brevig (2006). 6 Portfolios INTERVIEWS/ SURVEYS/ CONFERENCES Suggestions for Getting Started • “Start small” (e.g., focus on one curricular area). •Review critical dates (e.g., if student-led conferencing is going to occur). •Inform parents early regarding the purpose and plans for the portfolio. •Have students set goals early and revisit them periodically. •Have portfolios readily available for students to access. •Practise using the “language of reflection.” •Ideally, model self-assessment and goal-setting by maintaining a professional portfolio that you share with your students. (adapted from: Rolheiser, Bower, & Stevahn, 2000) Suggestions for Getting Started • Record what students say and do as you interview. • Transcribing may be required to complete surveys. • Consider tape recording student responses. • Create opportunities for students to practise student-led conferences with their peers and/or older students, before they conduct them with their parents/guardians. Resources: Ministry of Education (2005) (Appendix 7.3); Ministry of Education (2006b pp. 47–49); Ministry of Education (2006c, pp. 12–18); Ministry of Education (2003, p. 43). “The real contents of a portfolio are the child’s thoughts and his or her reasons for selecting a particular entry ... We need to discover the ever growing metacognitive voices of our children – voices that we (teachers) train to become competent and thoughtful tellers of the stories of their learning.” (Herbert, 1998, p. 584) Resources: Ministry of Education (2005) (Appendix 7.1); Ministry of Education (2006b) (Appendices 1 & 9); Ministry of Education (2006c) (Appendices 12-10 & 12); Ministry of Education (2003, p. 43). Journals/Logs Getting Started • Use sentence stems to guide entries. Resources: Ministry of Education (2005) (Appendix 6.5); Ministry of Education (2006, 3, 4, &5); Ministry of Education (2003, p. 44); Ministry of Education (2006) (Appendix 12-5); eworkshop.on.ca Self-Assessment: A Growth Continuum for Teacher Reflection Key Stages and Conditions Getting Started Gaining Momentum Consolidating and Extending Establishing Criteria Students respond to teachergenerated criteria. Students select criteria from a menu provided by teacher. Teacher and students negotiate criteria. Teaching Students How to Apply Criteria Examples of application of the criteria are provided. Description of how to apply criteria is provided. Modelling: examples and description of application of criteria are provided. Giving Feedback to Students on Their Self-Assessments Some feedback is provided by teacher and/or peers. Comprehensive feedback is provided by teacher and/or peers Comprehensive feedback that is explicitly linked to criteria is provided by teacher and peers. Feedback is given on more than one dimension of the student’s self-assessment. Feedback is specific; strengths and areas for growth are identified Multiple sources of specific feedback are available. Student has opportunity to respond to feedback. Student has chance to justify self-assessment to teacher and/or peers. Teacher and/or peers engage in dialogue about self-assessment. Goal Setting Teacher prescribes goal that is appropriate to student. Teacher provides menu of possible goals (based on data) that are appropriate for the student. Student constructs goals from data; goals are appropriate both to student and task. Classroom Norms Students self-assess Students self-assess regularly, sporadically, usually at the end usually at the beginning and/ of instruction. or end of instruction. A Growth Continuum is adapted from Rolheiser (2006). Students self-assess regularly throughout the course of instruction, using a variety of instruments. 7 References Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139–148. Booth, D., Green, J. & Booth, J. (2004). I want to read! Reading, writing and really learning. Oakville, ON: Rubicon. Ross, J. A. (2006). The reliability, validity, and utility of self-assessment. Practical Assessment Research & Evaluation, 11(10), 1–13. Ross, J. A., Hogaboam-Gray, A., & Rolheiser, C. (2002). Student selfevaluation in grade 5–6 mathematics: Effects on problem solving achievement. Educational Assessment, 8(1), 43–58. Brevig, L. (2006) The Reading Teacher, 59(6), 522–530. Saddler, B., & Andrade, H. (2004). The writing rubric. Educational Leadership, 62(2), 48–52. Bruce, L. B. (2001). Student self-assessment: Encouraging active engagement in learning. Dissertation Abstracts International, Vol. 62-04A, 1309. Spandel, V. (2006a). Assessing with heart. Journal of Staff Development, 27(3), 14–18. Chappuis, S., & Stiggins, R. J. (2002 ). Classroom assessment for learning. Educational Leadership, 60(1), 40–43. Cleland, J. (1999). We can charts: Building blocks for student led conferences. The Reading Teacher, 52(6), 588–595. Cooper, D. (2006). Collaborating with students in the assessment process. Orbit, 36(2), 20–23. Spandel, V. (2006b). In defense of rubrics. English Journal, 96(1), 19–22. Stiggins, R. (1999). Assessment, student confidence, and school success. Phi Delta Kappan, 81(3). White, B. Y., & Frederiksen, J. R. (1998). Inquiry, modeling, and metacognition: Making science accessible to all students. Cognition and Instruction, 16(1), 18–31. Creighton, D. (2000). What do rubrics have to do with teaching? Orbit, 30(4), 37–39. Cyboran, V. (2006). Self-assessment: Grading or knowing? Academic Exchange Quarterly, 10(3), 183–186. Dunning, D., Heath, C., & Suls, J.M. (2004). Flawed self-assessment: Implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(3), 69–106. Hart, D. (1999). Opening assessment to our students. Social Education, 63(6), 343–345. Herbert, E. (1998). Lessons learned about student portfolios. Phi Delta Kappan, 79(8), 583–585. Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat. (2006). Faciltator’s handbook: A guide to effective literacy instruction, Grades 4 to 6, Volume Two: Assessment. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Ministry of Education. (2005). A guide to effective instruction in writing, K–3. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Ministry of Education. (2006a). A guide to effective instruction in mathematics, K–6, Volume 4. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Ministry of Education. (2006b). A guide to effective literacy instruction, 4–6, Volume Two: Assessment. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Ministry of Education. (2006c). A guide to effective instruction in reading, K–3. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Ministry of Education (2006d). The Ontario curriculum, Grades 1–8: Language. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Ministry of Education (2002). The Ontario Curriculum unit planner. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Ministry of Education. (2003). Early math strategy: The report of the Expert Panel on Early Math in Ontario. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Rolheiser, C. (Ed.). (1996). Self-evaluation: Helping kids get better at it. Ajax, ON: VisuTronX. Rolheiser, C., Bower, B., & Stevahn, L. (2000). The portfolio organizer: Succeeding with portfolios in your classroom. Alexandra, VA: American Society for Curriculum Development. Rolheiser, C., & Ross, J.A. (2000). Student self-evaluation – What do we know? Orbit, 30(4), 33–36. Rolheiser, C. & Ross, J. A. (2001). Student self-evaluation: What research says and what practice shows. In R. D. Small & A. Thomas (Eds.), Plain talk about kids (pp. 43–57). Covington, LA: Center for Development and Learning. Retrieved October 26, 2007 http://www.cdl.org/resource-library/articles/self_eval.php. Additional Resources Brookhart, S. M., Andolina, M., Zuza, M., & Furman, R. (2004). Minute math: An action research study of student self-assessment. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 57(2), 213–227. Bruning, R.H., Schraw, G.J., & Ronning, R.R. (1995). Cognitive psychology and instruction (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall. Cassidy, S. (2007). Assessing “inexperienced” students’ ability to self-assess: Exploring links with learning style and academic personal control. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 32(3), 313–330. Cyboran, V. (2006). Self Assessment: Grading or knowing? Academic Exchange Quarterly, 10(3), 183–186. Earl, L. & Katz, S (2006). Rethinking classroom assessment with purpose in mind. Western and Northern Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in Education. Retrieved October 26, 2007 http://www.wncp.ca/. Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (1998). What’s worth fighting for out there? Mississauga, ON: Ontario Public School Teachers’ Federation. Jorissen, K. (2006). 3 skillful moves to assessment for the busy principal. Journal of Staff Development, 27(1), 22–26. Learner-Centered Work Group of the American Psychological Association’s Board of Education Affairs (1997). Learner centered psychological principles: A framework for school reform. Retrieved October 26, 2007 http://www.cdl.org/resource-library/articles/ learner_centered.php. Ministry of Education. (2006). A guide to effective instruction in mathematics, K–6. Volume Four: Assessment and home connections. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Ross, J. A., Rolheiser, C., & Hogaboam-Gray, A. (2000). Effects of self-evaluation training on narrative writing. Assessing Writing, 6(l), 107–132. Stiggins, R., & Chapuis, J. (2006). What a difference a word makes: Assessment FOR learning rather than assessment OF learning helps students succeed. Journal of Staff Development, 27(1), 1. Tan, K. (2004). Does student self-assessment empower or discipline students? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 29(6), 651–662.