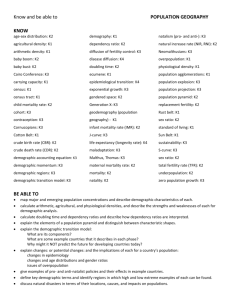

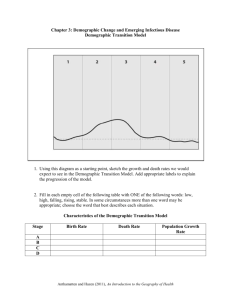

Qualitative data in demography

advertisement