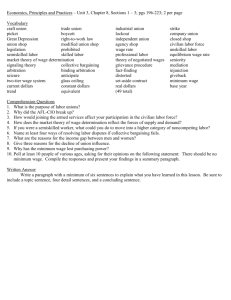

Recommendations for the National Minimum Wage

advertisement