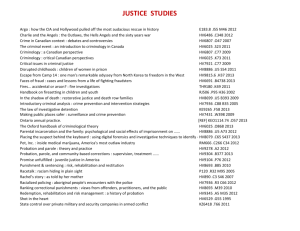

Are All Forms of Joint Crime Really "Organized Crime"?

advertisement