EU Monitor 28

Reports on European integration

September 8, 2005

The euro: Well established as

a reserve currency

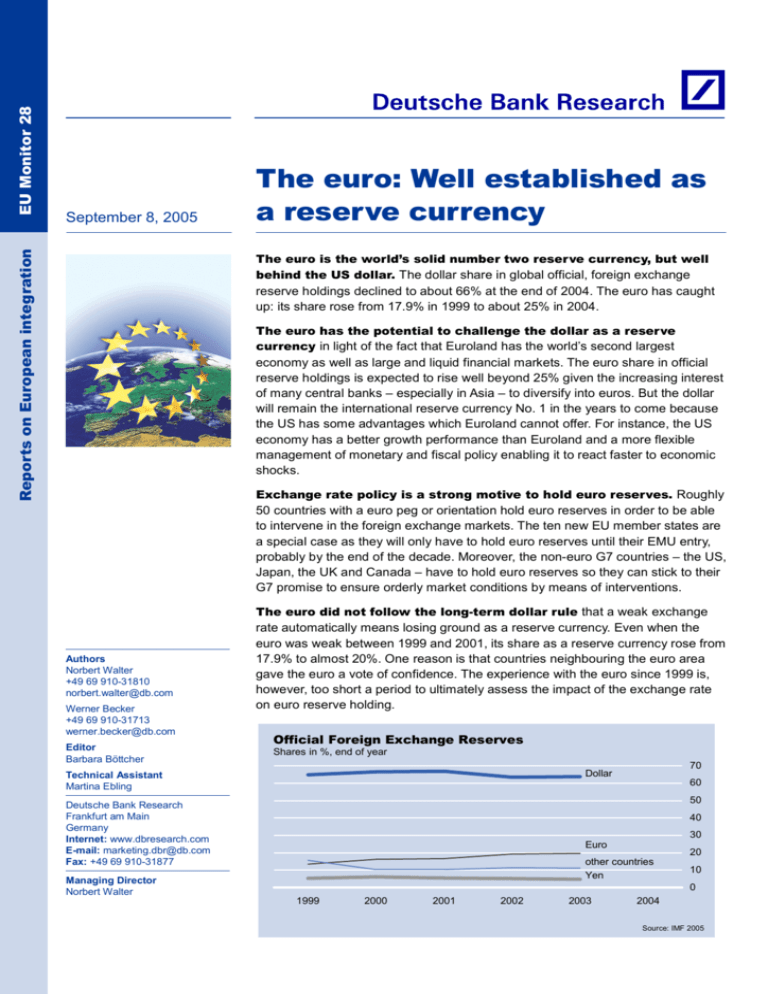

The euro is the world’s solid number two reserve currency, but well

behind the US dollar. The dollar share in global official, foreign exchange

reserve holdings declined to about 66% at the end of 2004. The euro has caught

up: its share rose from 17.9% in 1999 to about 25% in 2004.

The euro has the potential to challenge the dollar as a reserve

currency in light of the fact that Euroland has the world’s second largest

economy as well as large and liquid financial markets. The euro share in official

reserve holdings is expected to rise well beyond 25% given the increasing interest

of many central banks – especially in Asia – to diversify into euros. But the dollar

will remain the international reserve currency No. 1 in the years to come because

the US has some advantages which Euroland cannot offer. For instance, the US

economy has a better growth performance than Euroland and a more flexible

management of monetary and fiscal policy enabling it to react faster to economic

shocks.

Exchange rate policy is a strong motive to hold euro reserves. Roughly

50 countries with a euro peg or orientation hold euro reserves in order to be able

to intervene in the foreign exchange markets. The ten new EU member states are

a special case as they will only have to hold euro reserves until their EMU entry,

probably by the end of the decade. Moreover, the non-euro G7 countries – the US,

Japan, the UK and Canada – have to hold euro reserves so they can stick to their

G7 promise to ensure orderly market conditions by means of interventions.

Authors

Norbert Walter

+49 69 910-31810

norbert.walter@db.com

Werner Becker

+49 69 910-31713

werner.becker@db.com

Editor

Barbara Böttcher

The euro did not follow the long-term dollar rule that a weak exchange

rate automatically means losing ground as a reserve currency. Even when the

euro was weak between 1999 and 2001, its share as a reserve currency rose from

17.9% to almost 20%. One reason is that countries neighbouring the euro area

gave the euro a vote of confidence. The experience with the euro since 1999 is,

however, too short a period to ultimately assess the impact of the exchange rate

on euro reserve holding.

Official Foreign Exchange Reserves

Shares in %, end of year

60

50

Deutsche Bank Research

Frankfurt am Main

Germany

Internet: www.dbresearch.com

E-mail: marketing.dbr@db.com

Fax: +49 69 910-31877

Managing Director

Norbert Walter

70

Dollar

Technical Assistant

Martina Ebling

40

30

Euro

other countries

Yen

20

10

0

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

Source: IMF 2005

EU Monitor 28

2

September 8, 2005

The euro: well established as a reserve currency

Dominant dollar position

The dollar has been the key international trade, investment and

reserve currency for decades. Neither the D-mark nor the yen,

which gained some weight as international currencies in the 1970s

and 1980s, called the dominance of the dollar into question. But the

advent of the euro in 1999 brought the most dramatic change in the

international monetary system since the transition to flexible

exchange rates in the early seventies. It has been claimed –

surprisingly enough also by some American economists – that the

1

euro is likely to challenge the international position of the dollar in

view of the fact that the economic potential of the euro area is

similar to that of the US.

The euro: European answer

to globalisation

The introduction of the euro was the European answer to the

challenges of globalisation. It was primarily a political decision taken

to strengthen political cohesion among the members of the

European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and at the same

time promote the global role of Europe in monetary affairs and

beyond. But there are also valid economic arguments in favour of

EMU such as the elimination of intra-European foreign exchange

risks, the growth-stimulating convergence of interest rates and the

emergence of large and liquid euro financial markets.

Many questions concerning the euro’s

reserve currency role

This paper focuses on the development and the determinants of the

euro as an international reserve currency held by central banks or

monetary authorities. Therefore, it reviews the euro’s international

role in general and its status as a reserve currency in particular

since 1999. Many interesting questions arise: Which parameters will

determine the euro’s future role as reserve currency? How important

is the euro exchange rate in this context? Is the honeymoon of the

strong euro exchange rate already over with the currency having

peaked in January 2005 (at EUR 1.36/USD) and with the negative

referenda in France and the Netherlands in late May/early June

2005 pulling it down? What role will the euro have in a bipolar international monetary system alongside the dollar? What chance will

the euro have as a reserve currency of East Asian central banks?

ECB plays a neutral role

ECB monitors global use of the euro

The international use of a currency has some advantages for the

country that issues it. So far, the country that has benefited predominantly has been the US. For instance, international investors

enhance liquidity in financial markets and, more importantly, the

government benefits from seignorage. For its part, the ECB does not

actively promote the international role of the euro. Rather, the ECB

has explicitly declared that it pursues a neutral policy, i.e. it refrains

from hindering or promoting the international use of the euro. This is

true for all areas of international use including reserve holding by

central banks outside the euro area. However, the ECB regularly

monitors the international role of the euro and provides valuable

2

information about its global use.

Good euro performance in the international arena

Krugman matrix as yardstick

for international use

The euro’s international performance since 1999 can be illustrated

3

on the basis of the Krugman matrix which combines the three

classical functions of money – means of payment, unit of account

and store of value – with the international use of a currency by the

1

2

3

September 8, 2005

Robert Mundell (1998), The case for the euro – I and II, Wall Street Journal, March

24 and 25, A 22; C. Fred Bergsten (1997), The dollar and the euro, Foreign Affairs,

July/August, 83-95.

ECB (2005), Review of the international role of the euro.

P.R. Krugman (1997), Currencies and Crises, Cambridge (Mass.)

3

EU Monitor 28

private and official sectors. The three private functions and the first

two official ones are also reviewed in order to find out whether they

are relevant for the euro’s reserve status.

Roles of an international

currency

Private

Official

use as

Medium of

exchange

Vehicle

Unit of account

Invoice

Peg

Store of value

Banking

Reserve

Intervention

Dollar dominant in trade

invoicing

Private-sector use of the euro as a medium of exchange can, for

instance, be shown by the foreign exchange turnover in the

euro/dollar market. The euro/dollar segment is the most intensively

traded currency pair and the euro is the second most actively traded

currency in foreign exchange markets worldwide (accounting for

4

37% of transactions compared with 89% in case of the dollar ). It is

much more important than the yen/dollar currency pair (20%) and

also more important than the D-mark/dollar pair was in April 1998

before the start of EMU (20%). Surprisingly, the average daily

turnover in the global foreign exchange markets rose to USD 1.9

trillion in April 2004 (at current exchange rates), a 57% increase

over April 2001 when the preceding survey was carried out. Driving

market forces have been investors’ growing interest in foreign

exchange as an asset class alternative to equity and fixed income,

the rising importance of hedge funds and the more active role of

asset managers – including the managers of foreign exchange

5

reserves of central banks.

As to invoicing of international trade transactions the dollar is still

dominant with a global market share of almost 50%. Moreover, oil

and other commodities are invoiced in dollars. But the euro has

more or less assumed a regional role in trade transactions. For

instance, euro invoicing in Euroland’s exports and imports of goods

and services has grown notably, reaching a share of over 50% in

many EMU member countries in 2003.

Good euro performance in

financial markets

The emergence of larger and more liquid euro financial markets has

been the most important event for international institutional investors

including reserve managers of central banks. There has been strong

use of the euro as an issuing currency in international bond markets

right from the start of EMU. The euro’s share in international bonds

issuance has fluctuated between 34% and 44% since 1999, i.e. it

has been close to the dollar (39% – 49%) but well ahead of the yen

(below 10%). The total stock of euro-denominated debt securities

reached a share of more than 30% at the end of 2003 compared

with about 20% in 1998 just before the start of EMU. The share of

the dollar decreased from about 48% to 44% during this period, and

that of the yen from 20% to about 10%.

The euro is a regional

anchor currency

As an intervention currency the euro has been used predominantly

by countries neighbouring the monetary union. About 50 small and

medium-sized countries in Europe, the Mediterranean and Africa

have pegged their currency to the euro or orient their exchange rate

policy towards the euro. Accordingly, they have accumulated euros

as reserve currency.

The euro has caught up as

reserve currency

As regards the proper role of the euro as reserve currency, it is not

surprising that the dollar is still the star in official foreign currency

reserve holdings of the world’s monetary authorities five years after

4

5

4

Bank for International Settlements (2004), Triennial Central Bank Survey of

Foreign Exchange and Derivatives Market Activity in April 2004. Because two

currencies are involved in each transaction, the sum of the percentage shares of

individual currencies totals 200% instead of 100%.

By contrast, there was a substantial fall in global trading volumes between 1998

and 2001 due to the introduction of the euro and global progress in the

consolidation of the banking industry.

September 8, 2005

The euro: well established as a reserve currency

6

the introduction of the euro. According to IMF statistics the dollar

share peaked at 71% in 1999 (year-end figure) but declined to about

66% at the end of 2003 and stayed there in 2004. By contrast, the

share of the euro rose from 17.9% in 1999 to about 25% in 2004.

This increase reflects the fact that the substantial appreciation vis-àvis the dollar since spring 2002 has improved the euro’s image in

financial markets and also in the eyes of asset managers of central

banks, in particular in Asia.

The dollar is still the key currency

All in all, the euro has been a success story in the international

arena since 1999. The international use of the euro as a trade,

investment, anchor and reserve currency has increased

considerably. The euro has even topped the international role of its

12 legacy currencies including the D-mark. Although the euro has

been catching up, it has as yet only come close to the dollar in a few

areas such as international bond issues. The dollar is still the key

currency and there is hardly any doubt about its remaining in the

driver’s seat in the foreseeable future. Therefore, media “rumours of

the death of the international role of the dollar are greatly

exaggerated”, to paraphrase the famous quote of Mark Twain.

What factors determine the use of the euro as a

reserve currency?

Determinants of a reserve currency

While the rising international use of the euro in the private sector is

the result of microeconomic decisions of yield-seeking market

participants, the official use as an intervention, anchor and reserve

currency is primarily based on macroeconomic or political

considerations. The future volume of official euro reserve holdings

by non-EMU central banks and monetary authorities in the world will

be determined – as a review of experience with the international use

of the euro since 1999 shows – by the anchor and intervention

functions of the euro, by the development of the euro exchange rate

as well as the liquidity of euro-based financial markets. What does

this mean in detail?

Euro-oriented exchange rate policy

The above-mentioned roughly 50 small and medium-sized countries

with a euro peg or a euro orientation for their currency need to hold

official euro reserves in order to boost confidence in their peg and/or

their exchange rate policy and to be able to intervene in the euro

foreign exchange market if necessary.

New member states a special case

The ten new EU member states that are obliged to join EMU once

they meet the Maastricht convergence criteria are a special case.

Meeting the exchange rate criterion requires a tension-free

participation in the European exchange rate mechanism (ERM) II for

at least two years. Estonia, Lithuania and Slovenia joined ERM II in

June 2004, and Cyprus, Latvia and Malta followed in May 2005.

Participation in ERM II is, however, conceived to be the “waiting

room” for entry into EMU. Some small countries – the three Baltic

members and Slovenia – are expected to introduce the euro at the

earliest date, in 2007. By contrast, the four bigger new EU member

6

September 8, 2005

The IMF Annual Report 2005 has considerably revised the data on identified

holdings on foreign reserves due to changes in the underlying database on the

Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER). Both the dollar

and the euro share were reported to be between 2 to 6 percentage points higher

per annum in the period from 1999 to 2003 while the respective shares of the

yen, the pound sterling and unspecified currencies were much lower. The dollar

share peaked at 71% in 1999 compared with the message of the IMF Annual

Report 2004 that the dollar share peaked at 66.9% in 2001. The euro share

climbed from 17.9% in 1999 to a peak of 25.3% in 2003 whereas the IMF Annual

Report 2004 gave account of a rise of the euro share from 13.5% to 19.7% during

that period.

5

EU Monitor 28

states plan to join EMU only around the end of the decade. The

biggest hurdle on the road to EMU will be excessive budget deficits.

After EMU entry these countries will no longer have any need to

hold euro reserves as a policy tool.

G7 exchange rate cooperation

The non-euro G7 countries – the US, Japan, the UK and Canada –

basically need euro reserve holdings so they can stick to the G7

promise, repeatedly given by joint communiqués, “to monitor

exchange markets closely and cooperate as appropriate” in order to

ensure orderly market conditions. This cooperation includes joint

interventions in the foreign exchange market, for instance, by selling

euros to support the dollar. This implies that the US and the UK

should also hold official reserves in euros although both countries

are particularly reluctant to intervene in the foreign exchange

market.

Concerted G7 interventions cannot be

ruled out

In reality, the central banks of the G7 countries have not intervened

in the euro/dollar market since the joint action to support the weak

euro exchange rate in autumn 2000. But things have changed since

then. The euro exchange rate has risen considerably, on balance,

and a huge and unsustainable US current account deficit has

emerged causing increasing uncertainty for the dollar exchange

rate. Therefore, concerted international action aimed at establishing

orderly market conditions cannot be ruled out in the next few years.

Return-oriented investment strategy

Last but not least, a possible motive for virtually all non-EMU central

banks in the world to hold euro reserves could be to increase

returns on their national monetary wealth. For instance, one

investment strategy is to diversify in euros in order to reduce the risk

of over-concentration on the dollar. This is especially true for central

banks in East Asia with large dollar reserve holdings (see below).

How important is the exchange rate for use of the euro

as reserve currency?

Correlation between dollar exchange

rate and use as reserve currency

The long-term experience with the dollar as a reserve currency

shows that there is a long-term correlation between the development of the exchange rate and the dollar’s use as international

reserve currency. For instance, the weakness of the dollar exchange

rate in the 1970s has been associated with the rise of the D-mark

and the yen as alternative international reserve currencies at the

expense of the even then still dominant dollar. A further example is

the experience with the dollar and the D-mark or the euro since the

mid-1990s. The dollar’s share as a reserve currency rose from 59%

in 1995 to 71% in 1999 owing to a rising dollar exchange rate vis-àvis the D-mark – and later on vis-à-vis the euro – as well as sound

US fundamentals including buoyant growth.

The euro did not follow the

dollar correlation

But the euro did not follow the simple rule that a weak exchange

rate automatically means losing ground as a reserve currency. Even

when the euro was weak between 1999 and 2001, its share as a

reserve currency increased from 17.9% to almost 20%. Obviously,

neighbouring countries gave the euro a vote of confidence and

invested in it despite it lacking a direct track record.

Euro money and debt markets are

deemed to be as attractive as dollar

markets

But the international use of the euro as a reserve currency

continued to rise to about 25% in 2003 following the turnaround in

the euro/dollar exchange rate in spring 2002 and a substantial

7

appreciation of the euro. According to a recent central bank survey ,

7

6

The survey was carried out between September and December 2004 among 65

asset managers of central banks, see Robert Pringle and Nick Carver (2005),

Trends in reserve management – survey results, London, Central Banking

Publications.

September 8, 2005

The euro: well established as a reserve currency

the weaker dollar is a reason for many central banks to reduce the

dollar share of their official reserve holdings. It seems likely this

intention is not yet fully reflected in the end 2004 figure of a 24.9%

euro share.

The relatively short experience with the euro since 1999 has shown

that the correlation between the exchange rate and international use

as a reserve currency is less pronounced than one would think. The

reason is that the rankings of currencies in international use such as

the dollar and the euro tend to change quite slowly over time – on

the scale of years – whereas the exchange rate among them

8

changes rapidly – even within days .

Opportunity for the euro

It would, however, be too early to interpret the weakening of the

euro after the negative referenda in France and the Netherlands in

late May/early June 2005 as a starting signal for a reduction of the

euro’s share as an international reserve currency. Given the

increased uncertainty about future European integration and the still

lacklustre European growth performance, a weaker euro would not

be unjustified. Nevertheless, the dollar is expected to weaken due to

the excessive current account deficit, so the positive influence of the

exchange rate on the use of the euro as reserve currency should

basically remain intact.

Is there room for two leading reserve currencies?

The euro has potential to challenge

the dollar

The role of the euro in the international monetary system was

debated well before the start of EMU in 1999. Obviously, this issue

is again on the table in 2005. There is no simple answer to the

question whether the euro will be a serious challenge to the dollar in

terms of being an international currency including a reserve

currency. So far the answer has been that the dollar will remain

dominant. But there are indications that the euro has the capacity to

catch up further. The euro has the potential to challenge the dollar in

several areas of international use because the Euroland currency

9

fulfils two main preconditions .

Euroland is the second largest

economy

First, Euroland has the world’s second largest economy after the

US, well ahead of Japan. Although Euroland has a larger population

than the US it only produces the equivalent of 75% of US GDP at

current exchange rates. Euroland is the most important global

exporter, shipping about 13% of the world’s exports. But it absorbs

only about 12% of world imports, i.e. much less that the US with its

17% share reflecting the US role as a global growth engine.

Euroland produces about 21% of world GDP, compared with 27% in

the US. With a ratio of goods exports (extra-EMU) to GDP of about

13% Euroland’s degree of openness is higher than that of the US or

Japan.

Substantial progress in euro financial

market integration

Second, the introduction of the euro in 1999 was the catalyst for

pushing financial market integration in Euroland. Here, substantial

progress has been made in particular regarding the (interbank)

money market, which had been virtually fully integrated from day

one of EMU. There has also been substantial progress in euro bond

market integration. The liquidity of government bonds has risen

substantially, i.e. by governments focusing bond issues on a few –

8

9

September 8, 2005

Jeffrey A. Frenkel (2000), On the euro: the first 18 months, Deutsche Bank

Research, EMU Watch, Nr.87.

The euro will be to the dollar what Airbus Industries has become for Boeing, see

Norbert Walter (1998), Spitzenqualität, Der Euro wird für den Dollar, was Airbus

Industries für Boeing wurde, in: Maschinenmarkt, Das Industriemagazin,

Sonderausgabe.

7

EU Monitor 28

different – maturities. The high degree of liquidity in several national

government bond markets overcomes the disadvantage that there is

not a central government borrower in the euro area like the US

Treasury. Issuing activities have also flourished in the corporate and

mortgage bond markets. A salient feature was the introduction of

Euribor and Eonia as reference (interest) rates for financial market

operations including fixed income, futures and swaps.

FSAP is driving force

The integration process has been promoted by the ambitious

legislative programme of the Financial Services Action Plan (FSAP)

which was launched in 1999, essentially completed by mid-2004

and is now in the process of implementation. Money and debt

markets, which are very important for the diversification of central

banks into the euro, are working efficiently. But the financial markets

remain fragmented along the national border lines, for instance

10

regarding the equity markets and the retail banking markets .

There, different legal and tax systems are still major hurdles. But

those fragmented markets are not so important from the aspect of

the diversification of official foreign exchange reserves into euros.

The euro is a fully-fledged investment

alternative

By the same token, a recent survey among central banks has

concluded that the euro financial markets have reached the same

quality as dollar markets as far as the liquidity and the availability of

financial instruments in the money and debt markets are concerned.

Thus, if the quality of financial markets is no longer an argument for

choosing dollar assets, a major reason against diversification into

the euro is no longer valid from a central bank asset manager’s

point of view.

The euro has potential as reserve

currency

Against this background the euro is more or less a fully fledged

alternative to the dollar as a reserve currency. Thus the euro can,

and should, take more international responsibility in a bipolar

international monetary system. The euro has the potential to raise its

share well beyond the 25% posted for 2003 and 2004. In 2000,

Deutsche Bank Research estimated that the euro would be likely to

12

reach market shares of between 30 and 40% by 2010 . This is still

within reach with regard to the reserve currency status. It implies two

elements:

The dollar will remain No. 1 reserve

currency

Diversification into euros

11

— First, the dollar will remain the international reserve currency No.

1 in the years to come because the US has some advantages

which Euroland cannot offer. The US is a federal state and a

military superpower while Europe will remain in a politically

difficult situation for the time being since the French and Dutch

voted no in their referenda on the EU constitutional treaty.

Moreover, the US economy has a better growth performance

than Euroland and a more flexible macroeconomic management

regarding monetary and fiscal policy enabling it to react faster to

economic shocks.

— Second, an increasing role of the euro as reserve currency

implies that asset managers of non-EMU central banks –

especially in East Asia – must make decisions in favour of

diversifying and investing an increasing part of their foreign

exchange assets in euros.

10

11

12

8

Expert Group on Banking (2004), Financial Services Action Plan: Progress and

Prospects, Final Report.

See footnote 6.

Norbert Walter (2000), The Euro Second to (N)one, The American Institute for

Contemporary German Studies, German issues 23.

September 8, 2005

The euro: well established as a reserve currency

As things stand, the euro is the only serious candidate to challenge

the dollar in the international arena in the foreseeable future. Given

the importance of the dollar in Asia, the yen lacks the international

weight to become the third global pillar. The currency of the

emerging Asian giant China is still lacking the key preconditions – in

particular open, large and liquid financial markets – that would allow

it to play a role as an international reserve currency.

What will determine the asset management strategy of

East Asian central banks?

Asian central banks biggest reserve

holders

Central banks in East Asia are the biggest official reserve holders

investing predominantly in dollars. They have more than doubled

their currency reserves since the Asian crisis of 1997/98 and hold

almost 60% of global reserves of about USD 3.9 trillion at the end of

2004. The biggest Asian reserve holders are Japan (USD 823 bn),

China (USD 736 bn), Korea (USD 198 bn) and Taiwan (USD

13

242 bn) .

Currency composition of reserves

under review

Given the rising uncertainty surrounding the US current account

deficit and the dollar exchange rate it is compelling for central banks

with large dollar holdings to check the currency composition of their

reserves. One way to tackle the issue is to differentiate between two

types of accounts for official foreign exchange reserves:

Intervention account

On the one hand, an “intervention account” where funds must be

available at short notice in order to be able to intervene flexibly. This

account will be solely a policy tool and only focus on

macroeconomic targets.

Monetary wealth account

On the other hand, a “monetary wealth account” that will absorb the

remaining official foreign exchange reserves. Funds in this account

will be invested with the microeconomic aim of achieving an optimal

return on investment in order to enhance the national monetary

wealth.

Demand for higher performance

In the past, central banks were relatively conservative institutional

investors with a focus on (highly-rated) debt-denominated paper

(including medium and long-term maturities). They accepted lower

returns for less risk. Nevertheless, central banks did not ignore the

return aspect completely but put emphasis on an efficient portfolio

management including the use of arbitrage techniques and efficient

14

cash management . However, two events have triggered demand

for a higher performance from official reserves:

First, persistently low government bond yields have brought the

performance of central banks’ portfolios under pressure.

Substantial rise in reserves

New asset classes in

portfolio management

Second, global reserves have increased by a substantial 65%

during the past four years to the end of 2004, reaching a level – as

mentioned above – of about USD 3.9 trillion. Such high foreign

exchange reserves are definitely not needed for policy purposes.

Excess reserves are particularly suitable to be turned over to

professional asset management in order to enhance the return of

national monetary wealth and to transfer the profits to the shareholders – which are the finance ministers in most cases.

Obviously, many central banks around the globe stand ready to

invest in more risky asset classes including lower-rated bonds and

spread products in order to raise their yield, as the above-mentioned

13

14

September 8, 2005

Source: IMF; Central Bank of China (Taiwan)

John Francis Nugee (2005), Diversification in Central Bank Reserves

Management, State Street Global Advisors, Essays & Presentations, Fixed

Income.

9

EU Monitor 28

15

central banking survey has found out. Three-quarters of all central

banks interviewed conveyed the message that they have introduced

new asset classes in their portfolio management in the last 12 to 24

months. Unfortunately, there is hardly any information about

diversification into the euro on the part of Asian central banks.

Is there a way out of the dilemma for Asian central

banks?

Accumulation of large dollar reserves

East Asian central banks have accumulated huge dollar reserves in

recent years through interventions aiming to stabilise their exchange

rate vis-à-vis the dollar, thus supporting their exports. They invested

these sums to a very large extent in debt-denominated dollar assets,

thereby financing a substantial part of the US twin deficits in the

current account and the budget. For instance, East Asian central

banks increased their foreign exchange reserves by about USD 530

bn in 2004, thus financing about three-quarters of the huge US

current account deficit of 5.7% of GDP. This investment strategy has

also contributed to the relatively low level of US government bond

yields.

Idea of a revived Bretton Woods

System

There are different views on these US-Asian trade and currency

patterns. Some observers argue that there is a revived Bretton

16

Woods System and reserve accumulation will continue on the

basis of relatively stable exchange rates of Asian currencies vis-àvis the dollar. On the other hand it is argued that such a revived

Bretton Woods System is potentially unstable as the exchange rates

of Asian countries must also play a role in correcting the huge US

current account deficit. Thus, a noticeable appreciation of the

currencies of China and Japan (which have considerable bilateral

current account deficits with the US) is deemed to be appropriate.

The G7 has repeatedly conveyed the message to implement more

flexibility in exchange rates in Asia in recent years. However, more

exchange rate flexibility is now under way in East Asia after the

decision of China in July 2005 to suspend the dollar peg and to

move instead into a managed floating regime based on a basket of

17

currencies which takes account of major trading partners , foreign

debt flows and FDI. Nevertheless, China is still pursuing a cautious

approach in exchange rate policy. There was only a small

appreciation of the yuan against the dollar in the first few weeks (of

about 2%) in order to allow a smooth adjustment of the Chinese

foreign trade sector. Such a small step will hardly contribute to a

correction of the large US current account disequilibrium. A further

(gradual) appreciation of the yuan against the dollar is necessary

and expected.

China changes the exchange

rate regime

Impact on other Asian countries

The change in China’s exchange rate regime has repercussions on

exchange rate policies in the region. While Malaysia has also lifted

its dollar peg, most other East Asian countries are pursuing a

managed floating approach aimed at maintaining export competitiveness, i.e. avoiding a higher exchange rate against the yuan

and allowing only a moderate appreciation against the dollar. So far

only Korea has tolerated a noticeable appreciation against the

dollar, and Japan ceased interventions in the dollar/yen market in

April 2004 (though not causing any significant appreciation in the

yen).

15

16

17

10

See footnote 6.

Michael Dooley, David Folkerts-Landau, Peter Garber (2003), An Essay on a

Revived Bretton Woods System, Deutsche Bank, Global Market Research.

They include not only the US, Euroland, Japan and Korea but also Singapore, the

UK, Malaysia, Russia, Australia, Thailand and Canada.

September 8, 2005

The euro: well established as a reserve currency

Asset management dilemma

Given this background, Asian central banks are in an asset

management dilemma. On the one hand there are good arguments

for them to refrain from putting all their eggs in one basket and to

diversify at least a part of their reserves into euros. If the central

banks were to do so to a meaningful extent they would risk

triggering a noticeable depreciation of the dollar against the euro

and their local currencies. This would, however, also imply a

devaluation of their huge dollar reserves in terms of national

currencies. Therefore, the East Asian central banks have been

opposed to diversifying official reserves into euros. Obviously, there

is no easy way out of this dilemma.

Window of opportunity for the euro in

Asia

The upshot is that most Asian central banks are likely to continue to

accumulate foreign exchange reserves, albeit at a slower pace after

the change in the Chinese exchange rate regime. While the bulk of

business will still be in dollars, the euro has the chance to win a

somewhat bigger role in the important “Asian battlefield” and thus to

increase the euro’s role as a reserve currency.

Norbert Walter, (+49 69 910-31810 norbert.walter@db.com)

Werner Becker, (+49 69 910-31713 werner.becker@db.com)

September 8, 2005

11

EU Monitor

ISSN 1612-0272

Payments in Europe: Getting it right

Financial Market Special, No. 27 ........................................................................................................August 29, 2005

EU in crisis, Free trade, Direct Investment,

Eastern Europe’s textile and clothing industry

Reports on European integration, No. 26 .................................................................................................July 13, 2005

EU Savings Tax Directive is close to the finish line

Financial Market Special, No. 25 ............................................................................................................ May 19, 2005

Post-FSAP agenda: Window of opportunity

to complete financial market integration

Financial Market Special, No. 24 .............................................................................................................. May 6, 2005

Stability pact, Croatia, Integrated research policy

Reports on European integration, No. 23 ................................................................................................ April 28, 2005

Savings bank reform in France:

Plus ça change, plus ça reste – presque – le même

Financial Market Special, No. 22 .............................................................................................................. May 3, 2005

Fiscal policy, Chemical industry, Social policy

Reports on European integration, No. 21 .......................................................................................... January 14, 2005

All our publications can be accessed, free of charge, on our website www.dbresearch.com

You can also register there to receive our publications regularly by e-mail.

Ordering address for the print version:

Deutsche Bank Research

Marketing

60262 Frankfurt am Main

Fax: +49 69 910-31877

E-mail: marketing.dbr@db.com

© 2005. Publisher: Deutsche Bank AG, DB Research, D-60262 Frankfurt am Main, Federal Republic of Germany, editor and publisher, all rights reserved. When

quoting please cite “Deutsche Bank Research“.

The information contained in this publication is derived from carefully selected public sources we believe are reasonable. We do not guarantee its accuracy or

completeness, and nothing in this report shall be construed to be a representation of such a guarantee. Any opinions expressed reflect the current judgement of

the author, and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Deutsche Bank AG or any of its subsidiaries and affiliates. The opinions presented are subject to change

without notice. Neither Deutsche Bank AG nor its subsidiaries/affiliates accept any responsibility for liabilities arising from use of this document or its contents.

Deutsche Banc Alex Brown Inc. has accepted responsibility for the distribution of this report in the United States under applicable requirements. Deutsche Bank

AG London being regulated by the Securities and Futures Authority for the content of its investment banking business in the United Kingdom, and being a member

of the London Stock Exchange, has, as designated, accepted responsibility for the distribution of this report in the United Kingdom under applicable requirements.

Deutsche Bank AG, Sydney branch, has accepted responsibility for the distribution of this report in Australia under applicable requirements.

Printed by: HST Offsetdruck Schadt & Tetzlaff GbR, Dieburg

ISSN Print: 1612-0272 / ISSN Internet and e-mail: 1612-0280