Voices of Feminism Oral History Project: Vázquez, Carmen

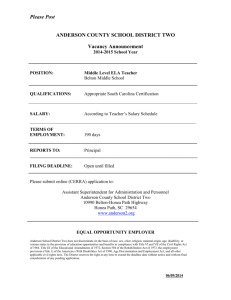

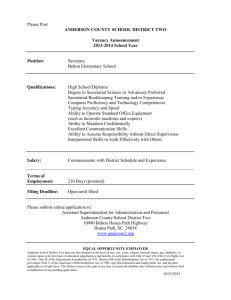

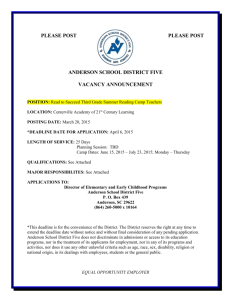

advertisement