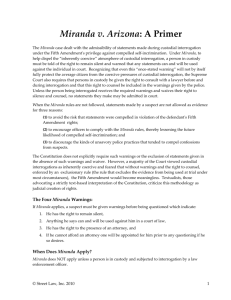

The Refusal to Clarify Equivocal Invocations of

advertisement