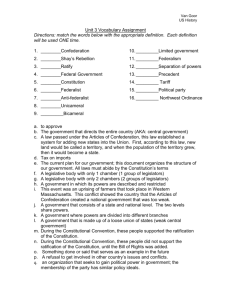

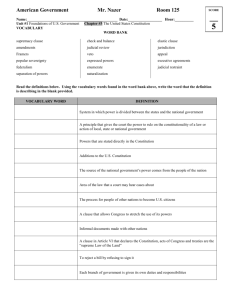

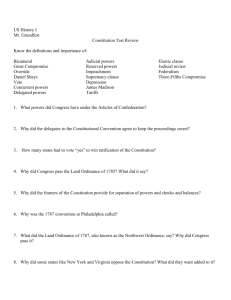

separation of powers as ordinary interpretation

advertisement