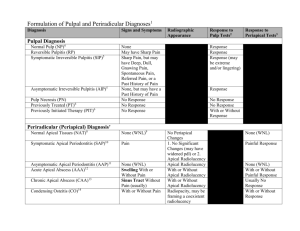

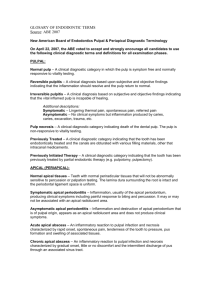

Identify and Define All Diagnostic Terms for Periapical/Periradicular

advertisement