By the power of truth, I, while living, have conquered the

advertisement

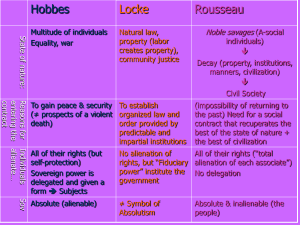

Whitehill 1 Brandon Whitehill Mr. Solomon Philosophy 10 Jan. 2014 Vi Veri Veniversum Vivus Vici By the power of truth, I, while living, have conquered the universe. Since the conception of the first human, philosophers, psychologists, and sociologists have often embarked upon a quest to find the purpose of humanity as a function of its time and place. Such is the burden of existing; humans are faced with a quagmire that pits conventionality and conformity against prospect and progress. In political philosophy, such figures as John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau have proposed the ideal of a social contract: a unifying force transcending time and space to which members of some harmonious unit act in tandem to achieve more than they could in isolation. Despite foundational discrepancies in their writings, each philosopher fundamentally agreed that the society which flourishes is that where the people surrender some liberty under the auspice that others will do the same, thus creating a collective understanding of law and governance. Rousseau theorizes, “[The social contract] can be reduced to the following terms: Each of us puts his person and all his power in common under the supreme direction of the general will; and in a body we receive each member as an indivisible part of the whole.” In its most quintessential state, the social contract superintends humanity like the invisible hand directs its commerce; an intangible yet indispensable fulcrum between civility and chaos. The tendrils of its influence are omnipotent in a world that yearns for order. Not every exhibition of the contract, however, is in its most quintessential state. Both the signatory and the executor are capable of breaching the trust. The former may take too much liberty and commit an act against his fellow countrymen while the latter may take too much liberty and seek to oppress and subjugate its constituents. While both involve a detrimental imbalance of liberty, one is much harder to mend than the other, for the government can easily incarcerate belligerence while the huddled masses are left perilous to combat a tyrannical government in which they have already entrusted their freedoms. It seems that the only remedy for such totalitarianism is open and resolute revolution in which the original architects of the government itself revoke their allegiance and liberty by whatever means they deem necessary. With the consent of the governed restored, the veterans of revolution teach their posterity to beware of corruption and stand as an unwavering sentinel for the integrity of the social contract. Thus the audience of the film V for Vendetta is immersed into a portrait of England in 2020 in which the contract has been commandeered by the repressive Norsefire party. Under the dictum “Strength through Unity. Unity through faith,” the government controls its people through an anatomical structure: the eyes and ears serving as perpetual video and audio surveillance; the mouth, propaganda broadcasted on television; the hand, law enforcement patrolling the streets; and the nose, secret, investigative police. In the midst of perpetual war, famine, disease, and degeneration, dictator Adam Sutler exploits the devices of fear and intimidation, offering a new era Whitehill 2 that would foster peace and tranquility—that is, as long as the people surrender their natural rights in return. Though the pressures of conforming in such a society are compelling, the film follows the quarry of a vivacious, vindictive vigilante to subvert the system that his fellow Londoners have come to tolerate. With malice aforethought, the masked man known only as “V” systematically abducts and murders government officials, detonates symbolic buildings, and infiltrates the citadels of government whilst trumpeting his zealous sentiment: While the truncheon may be used in lieu of conversation, words will always retain their power. Words offer the means to meaning, and for those who will listen, the enunciation of truth. And the truth is, there is something terribly wrong with this country, isn't there? Cruelty and injustice, intolerance and oppression. And where once you had the freedom to object, to think and speak as you saw fit, you now have censors and systems of surveillance coercing your conformity and soliciting your submission…Fear got the best of you, and in your panic you turned to the now high chancellor, Adam Sutler. He promised you order, peace, and all he demanded in return was your silent, obedient consent. For V, this crusade against the government is not circumstantial. Rather he is facilitating a revolution of ideas and reform so that the people of London may seize the government that is truly theirs and revel in the freedoms of representative democracy. Surely Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau would decry such a perversion of their philosophies; they envisioned the government as a transparent mediator, not an ominous vortex that plunders the natural rights of every man, woman, and child. On the basis that one man’s terrorist is another man’s proverbial freedom fighter, V acts not as an individual with grievances, but as an everlasting idea in favor of such an illustrious notion as the social contract. V is no more than a product of his milieu, but one who is not content with standing idly as the laws of his country slowly suffocate the natural rights endowed to us by our Creator. Unlike the great Socrates who stood stringently with the flawed Athenian law against Crito’s pleas, V elects to punish those responsible for decimating society—after all the diction was no coincidence; a contract itself implies that the parties involved are bound to compliance by a supreme standard of righteousness. V shows an impressionable audience that no ruler who deprives freedoms should be free from deprivation himself. The conundrum then becomes where to reconcile between the evils of repressive government and the anarchic vigilantism of V. Somewhere amid this dynamic tension lies the precious quintessential state of the social contract in which a delicate, sublime balance exists. No government possesses the right to prey on its people, while no person is warranted in truculence. But as both history and V for Vendetta demonstrate, one man with courage is a majority potentially capable of shattering the paradigm that so captivates the present mindset. Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau offered the world an alternative to self-preservation by joining together in congeniality. V offered England an alternative to tacit submissiveness by rising to regain control of their sovereignty. By acting with the vitality of an idea rather than the vulnerability of his body, V ensures himself and his movement victory well beyond his own physical demise. Concluding with a valorous votive, V vindicates his vendetta as a victim of the villain which he is virulently vilifying, as even in his vivid vanquish he victoriously vouchsafes, “Beneath this mask there is more than flesh. Beneath this mask there is an idea, Mr. Sutler, and ideas are bulletproof.” V for Vendetta verifies that one man with courage, with virtue, with vigor is indubitably enough to ensure the subsistence of the social contract today, tomorrow, and always.