SELF

DISCLOSURE

HOW TO MANAGE THE RISK OF

MEDICARE FRAUD AND ABUSE

When you discover an incident of noncompliance

with Medicare/Medicaid regulations, step forward

and notify the authorities before the government or a

whistleblower takes the problem out of your hands.

F

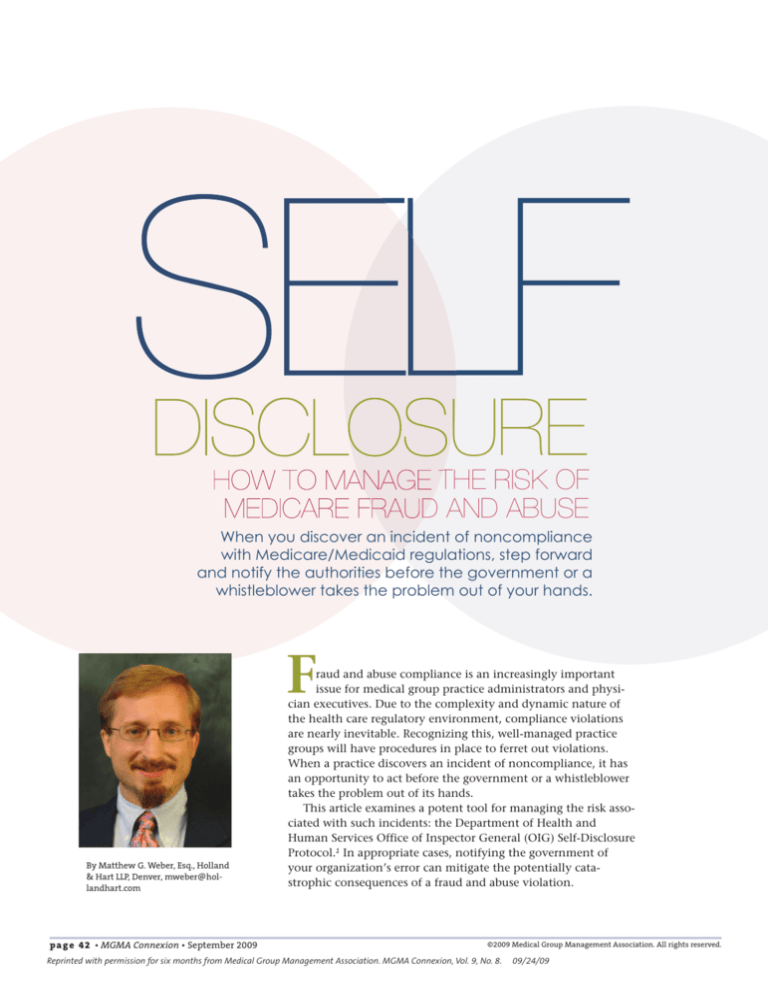

By Matthew G. Weber, Esq., Holland

& Hart LLP, Denver, mweber@hollandhart.com

p a g e 4 2 • MGMA Connexion • September 2009

raud and abuse compliance is an increasingly important

issue for medical group practice administrators and physician executives. Due to the complexity and dynamic nature of

the health care regulatory environment, compliance violations

are nearly inevitable. Recognizing this, well-managed practice

groups will have procedures in place to ferret out violations.

When a practice discovers an incident of noncompliance, it has

an opportunity to act before the government or a whistleblower

takes the problem out of its hands.

This article examines a potent tool for managing the risk associated with such incidents: the Department of Health and

Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG) Self-Disclosure

Protocol.1 In appropriate cases, notifying the government of

your organization’s error can mitigate the potentially catastrophic consequences of a fraud and abuse violation.

©2009 Medical Group Management Association. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission for six months from Medical Group Management Association. MGMA Connexion, Vol. 9, No. 8.

09/24/09

Risk Management

Pros, cons to disclosing your

group’s mistake

The OIG protocol is intended for matters

that may involve potential fraud against

federal health care programs. It’s not meant

to cover mere inadvertent billing errors or

Medicare overpayments, which can be handled through other avenues, such as reporting to the Medicare contractor. Nor is it

intended for Stark Act violations, unless the

same conduct implicates the Anti-Kickback

Act, as well.2 Most self-disclosures involve

fraudulent overpayments, billing/coding violations, transgressions of the antikickback

act or Stark law, or the hiring of excluded

individuals. Even when the protocol applies, the decision to use it requires careful

investigation, evaluation, judgment and the

assistance of legal counsel.

Self-disclosure has both benefits and

risks.

Benefits of self-disclosure

On the benefit side, the OIG encourages

self-disclosure, and it may be more lenient

toward providers who follow the protocol.

For instance, if the OIG settles the matter, it

may base its settlement offer on a financial

impact assessment at the lower end of the

available range by looking at antikickback

damages (based on the value of the improper payments or remuneration) rather

than Stark damages (based on the value of

improper claims).3 It may also reduce the

multiplier it applies to the financial impact

assessment.

Also, following the protocol may avoid

the presumptive imposition of a corporate

integrity agreement or corporate compliance agreement that could otherwise burden your practice with costly oversight

obligations for years to come.4

Self-disclosure gives your organization a

chance to gain control over the situation

and cast the disclosed incident in a manner

that avoids misunderstandings by the government.

Risks of self-disclosure

On the other hand, self-disclosure entails

substantial risks. The protocol provides no

guarantees of leniency, immunity or benefits. In fact, the OIG may deny all benefits if

it perceives that your practice has not followed the protocol in good faith or in a

timely manner. Further, resolving issues

through self-disclosure can be expensive

and disrupt daily operations and employee

morale. Making a self-disclosure can trigger

investigation by the OIG, other agencies or

potential civil litigants. Moreover, providing

information to the government may create

waiver issues related to the attorney-client

privilege and work-product protections.

In appropriate cases, notifying the government of your

organization’s error can mitigate the potentially catastrophic consequences of a

fraud and abuse violation.

Other disclosure considerations

Other issues may be relevant to the disclosure decision, including:

• The strength of the evidence of intent to

defraud. Is there evidence of recklessness

or deliberate indifference?;

• The likelihood of a whistleblower

coming forward;

• The strength of the compliance program;

• The likelihood of criminal exposure; and

• Whether disclosure should be made to

the OIG or another agency/entity.5

Make your self-disclosure decision in a

timely manner to avoid losing the benefits.

For example, the False Claims Act states

that providers who effectively self-disclose

within 30 days of obtaining information

about a violation may limit their damages

to double rather than triple.6

see

Self disclosure, p a g e

44

mgma.com

• Search: “fraud and abuse”

• Contact: MGMA Health Care

Consulting Group –

mgma.com/consulting

• Store: Item 6802 for the Compliance Guide for the Medical

Practice

©2009 Medical Group Management Association. All rights reserved.

MGMA Connexion • September 2009 • p a g e 4 3

Reprinted with permission for six months from Medical Group Management Association. MGMA Connexion, Vol. 9, No. 8.

09/24/09

Self disclosure

from page 43

What to do – Five steps

You need an action plan for your practice to

support the decision-making and self-reporting process. With the assistance of legal

counsel, design the plan around five steps:

A convincing audit is important to demonstrate that

• Define the scope of the trangression;

your group has remediated

• Preserve relevant documents;

the problem and eliminated

• Investigate;

• Remediate; and

• Audit.

Define the scope – To determine the scope

of the issue, your group’s legal counsel or

counsel’s delegate should interview the

source of the internal report and other central witnesses. Often, this initial effort uncovers additional allegations. This is helpful

to avoid the discovery of other issues after

the initial disclosure, necessitating supplemental disclosures. A close examination of

documents may also be necessary to better

understand the scope of the allegations.

Preserve relevant documents – You must secure relevant documents as soon as your organization receives notice that a federal

investigation may take place — or risk criminal prosecution.7 Cast a wide net: Preserve

both hard-copy and electronic files. Ensure

that e-mail and other electronic data are not

inadvertently destroyed through regular

purging cycles. In appropriate cases, qualified forensic experts may make copies of

your hard drives to preserve electronic evidence. Depending on the size of your practice, you may have to distribute a memo to

employees instructing them not to destroy

relevant documents and data.

Investigate – The OIG protocol requires a

complete investigation of a fraud-and-abuse

disclosure.8 A thorough investigation can be

costly, but it’s far better for your practice to

undertake that responsibility than to wait

for the government to conduct its own investigation. The investigation will usually

pick up where the initial “define the scope”

inquiry left off and then focus on the details of the incident. Anyone allegedly involved should not have a role in the

investigation, which should be directed by

legal counsel.

Attorneys who specialize in fraud-andp a g e 4 4 • MGMA Connexion • September 2009

the need for the OIG to

continue external oversight

through a corporate integrity agreement or corporate compliance

agreement.

abuse investigations follow procedures designed to increase the confidentiality, integrity and reliability of the process. For

instance, they compartmentalize information obtained in witness interviews to avoid

possible breaches of confidentiality and polluting witnesses’ memories with information from others. Seasoned lawyers will

advise your employees — sometimes called

“civil Miranda advisements” — to let them

know, among other things, that they represent only the practice, if that entity hired

the lawyers. In such cases, counsel does not

represent the employee. Employees’ cooperation is expected and they are to maintain

the confidentiality of interviews to protect

the practice’s attorney-client privilege. The

attorneys will explain that the privilege belongs to the practice and that the practice

has the right to waive the privilege and

share the information with others, including the government.

Remediate – Remediation is critical to successful self-disclosure. The facts of each case

will drive the remediation plan, but most

remedial efforts aim to:

• End the noncompliant conduct

(including taking appropriate

disciplinary action);

©2009 Medical Group Management Association. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission for six months from Medical Group Management Association. MGMA Connexion, Vol. 9, No. 8.

09/24/09

• Improve procedures, policies, controls

and systems; and

• Train members of the practice in

appropriate conduct.

Remediation may also include refunding

payments to the fiscal intermediary or others. The protocol, however, states that the

OIG should approve any such refunds.9

Audit – Taking remedial action alone is

not enough; your group also must demonstrate that the action was effective. An audit

will document the impact of the remediation. Depending on the circumstances, you

may want to consider hiring a consultant to

conduct the audit to provide the OIG with

an independent assessment. A convincing

audit is important to demonstrate that your

group has remediated the problem and

eliminated the need for the OIG to continue external oversight through a corporate integrity agreement or corporate

compliance agreement.

An effective tool against fraud and

abuse

As of mid-2008, the OIG protocol had accepted 379 disclosures of Medicare fraud

and abuse. Of those, 165 were resolved, returning more than $118 million to the

Medicare Trust Fund. Since then, the rate of

recovery has accelerated, with total recoveries most likely reaching or exceeding the

$200 million mark. With the additional

guidance provided in the OIG Open Letters

of April 24, 2006, and April 15, 2008, the

provider community appears increasingly

interested in using the protocol. Applied appropriately, self-disclosure offers an effective

tool to mitigate compliance risk for medical

groups confronting potential fraud and

abuse violations.

join the discussion: Has your organization voluntarily disclosed a fraud-and-abuse incident to the

OIG? Tell us at mgma.com/connexioncommunity or

connexion@mgma.com

Resolution

The self-disclosure process is not a speedy

one. Anecdotal evidence suggests that, in

the past, only about half the disclosures

were resolved within a year from filing. The

OIG announced its intention to resolve disclosures more promptly in its April 15,

2008, Open Letter to Providers. As part of

that initiative, the OIG established new

deadlines requiring more timely action by

those making disclosures.

Self-disclosure normally ends through

settlement. The size of the settlement depends on numerous factors, including

whether the financial impact on Medicare is

measured by the low or high end of the

range, the size of the multiplier applied to

the financial impact number and whether a

corporate integrity agreement is involved.

Also, depending on the allegations and the

scope of the release desired, agencies other

than the OIG may get involved in the settlement, which can affect the terms.

notes

1. Provider Self-Disclosure Protocol, 63 Fed. Reg. 58,339

(Oct. 30, 1998).

2. Open Letter to Health Care Providers, March 24,

2009, available at http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/

openletters/OpenLetter3-24-09.pdf (accessed

7/17/09).

3. Open Letter to Health Care Providers, April 24, 2006,

available at www.oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/openletters/Open%20Letter%20to%20Providers%202006.pd

f (last accessed 1/9/09).

4. Open Letter to Health Care Providers, April 15, 2008,

available at www.oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/openletters/OpenLetter4-15-08.pdf (last accessed 1/9/09).

5. This article is limited to the OIG protocol and does

not discuss self-reports to others such as fiscal intermediaries, the United States Attorney General’s office

or state Medicaid Fraud Control Units.

.

6. 31 U.S.C. § 3729(a)

7. 18 U.S.C. § 1519.

8. Open Letter to Health Care Providers, April 15, 2008.

9. See Protocol at 58,403.

©2009 Medical Group Management Association. All rights reserved.

MGMA Connexion • September 2009 • p a g e 4 5

Reprinted with permission for six months from Medical Group Management Association. MGMA Connexion, Vol. 9, No. 8.

09/24/09