China's Demographic Shifts - Stanford Center on Longevity

advertisement

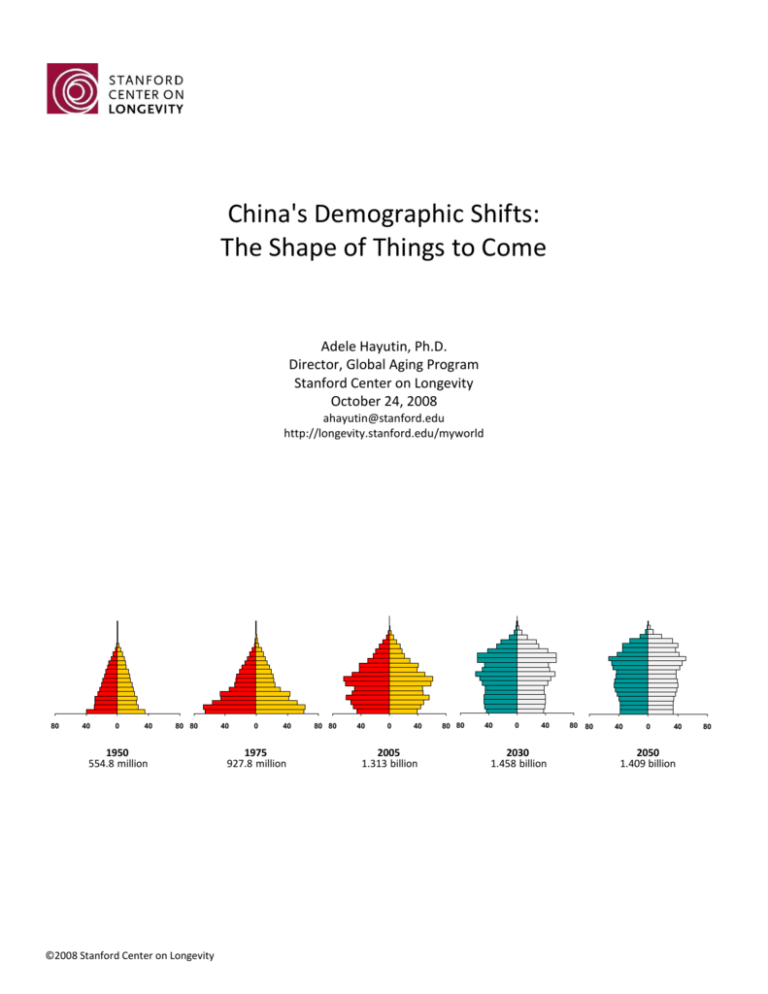

China's Demographic Shifts: The Shape of Things to Come Adele Hayutin, Ph.D. Director, Global Aging Program Stanford Center on Longevity October 24, 2008 ahayutin@stanford.edu http://longevity.stanford.edu/myworld 80 40 0 40 80 80 1950 554.8 million ©2008 Stanford Center on Longevity 40 0 40 1975 927.8 million 80 80 40 0 40 2005 1.313 billion 80 80 40 0 40 2030 1.458 billion 80 80 40 0 40 2050 1.409 billion 80 Contents This briefing provides an overview of population aging in China and illustrates key workforce implications. The document is organized as follows: Summary Demographic Drivers Fertility Life Expectancy Population Age Structure Speed of Aging % 65+ Median Age Changing Age Mix Population Growth by Age Bracket Workforce Implications Workforce Growth by Age Bracket Economically Active Population Demographic Dividend Worker-to-Retiree Ratios Urbanization Appendix A: Alternative Fertility Scenarios Appendix B: Comparative Reference—India, South Korea, Japan, and U.S. Note on Sources: This briefing relies on the United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast, unless otherwise noted. Page 2 Summary China’s fertility declines and increasing longevity will produce an age structure top heavy with old people. 80 40 0 40 80 80 40 0 40 80 80 40 0 40 80 80 40 0 40 80 80 40 1 0 40 1950 1975 2005 2030 2050 554.8 million 4% 65+ 927.8 million 4% 65+ 1.313 billion 8% 65+ 1.458 billion 16% 65+ 1.409 billion 24% 65+ 80 Population in millions by five-year age bracket; males on left, females on right Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast China is rapidly aging; by 2050 half the population with be over 45 and a quarter of the population will be age 65 or older. Because of its early and steep fertility decline, China will age sooner and faster than other developing countries. China's age structure will soon be top heavy with old people. The absolute number of children and young workers will decline sharply. Without a dramatic increase in fertility, population gains will occur only in the older age brackets. The workforce will rapidly age as the number of young workers declines; total working-age population will peak in 2015 at about 1 billion, and then fall 13% by 2050. Total population is projected to shrink by 2030. Over the past several decades China has benefited from the demographic dividend of an increased number and share of working-age people coupled with high productivity growth. China has a few more years to capitalize on this demographic dividend. After that, the projected decline in workingage population will pose significant challenges for China’s sustained growth: absent sustained productivity gains and labor market changes, China's economic engine could stall. Thus, we can expect greater pressure for productivity gains as well as changes in labor market structure. A further demographic challenge will be the doubling of the urban population to 1 billion by 2050; by then, 73% of China's 1.4 billion people will live in urban areas. Page 3 Demographic Drivers China’s fertility rate plunged in the 1970s even before the one-child policy; the rate is projected to remain below replacement level. 2 Fertility (Births per Woman) 7 6 5 4 Replacement rate = 2.1 3 2 1.7 1 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast China enjoyed an especially sharp increase in longevity during the late 1960s. 3 Life Expectancy at Birth, in years 80 73.7 Women 70 70.5 Men 60 50 40 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast Two major factors determine population aging. First is declining fertility, which reduces the number of children. Second is increasing longevity which increases the number of old people. Fertility in the developing world has dropped by half since about 1970, from 6.0 to 2.9 births per woman. China experienced one of the world's fastest declines in fertility, dropping from 6 births per woman in 1955 to less than 2 in the early 1990s. While longevity gains have occurred globally, China enjoyed an especially steep increase in life expectancy —from 50 to 60—during the late 1960s. Life expectancy reached 72 in 2005 with continued increases forecast over the next half century. Page 4 Population Age Structure China is rapidly aging; by 2050 a quarter of the population will be age 65 and older; half the population will be over 45. 4 Median Age 32.5 41.3 45.0 65 and Over 15 to 64 Under 15 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 2005 1.313 billion 8% 65+ 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 80 60 40 20 2030 1.458 billion 16% 65+ 0 20 40 60 80 2050 1.409 billion 24% 65+ Population in millions by five-year age bracket; males on left, females on right Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast This series of histograms shows how China changes from a society with a broad base of young people to an aging society top heavy with old people. Each histogram above shows the population in five-year age brackets, with children on the bottom and old people at the top; males are on the left and females on the right. The impact of the 1970s fertility decline and the 1979 one-child policy can be seen at the bottom of the 2005 histogram: as fewer children are born, the histogram’s base narrows. With a 2005 fertility rate of only 1.7—well below the 2.1 replacement rate—China already has a decreasing number of children as shown by the narrowing of the histogram’s base. At the same time, the top of the histogram widens as life expectancy increases and more people live longer, moving into the upper age brackets. In 1950, when China had a pyramid shaped age structure with a broad base of young people, only 4% of the population was 65 or over, but by 2005, the share of 65+ had increased to 8%. The share is projected to increase to 16% by 2030, slightly higher than the current U.S. share, and much higher than the projections for most other developing countries. Page 5 Speed of Aging Due to its steep fertility declines, China’s median age has increased sharply, from 20 in 1970 to 33 in 2005. 5 Median Age, in years 60 55 Japan 50 South Korea 45 China 40 US 35 India 30 25 20 15 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast 6 China is aging faster than the US and India. Percent 65+ 40% 35% Japan 30% South Korea 25% China 20% US 15% 10% India 5% 0% 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast The simultaneous increase in life expectancy and a precipitous drop in fertility contributed to the sharp increase in China’s median age beginning in 1970. At that time, half the population was younger than 20. By 2030 half the population will be older than 41, compared with 39 for the US. The combination of a sharp fertility decline and a steep longevity gain results in an “age wave” beginning in 2015, as the share of the population 65+ begins a steep increase. By midcentury, almost a quarter of the population will be age 65 and over. Page 6 Changing Age Mix 7 China’s workforce will peak around 2015. Age Mix (millions) Total Population (millions) 1,500 1,000 900 800 1,250 65+ 15-64 700 1,000 600 500 750 400 < 15+ 500 300 200 250 65+ 100 0-14 0 1950 15-64 0 1975 2000 2025 2050 1950 1975 2000 2025 2050 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast This age mix chart shows the size and growth of the three age major groups. The population aged 65+ has been steadily increasing and will more than triple, growing from 100 million in 2005 to over 300 million by 2050. Due to the steep fertility decline, the number of children has been declining since 1975. This steep decline in number of children will in turn decrease the size of the working-age population. Working-age population is projected to peak in 2015, then fall 14% by 2050. Total population is projected to start declining in 2030. Page 7 Changing Age Mix The number of children and young workers will decline sharply. Population gains will occur only in the older age brackets. 8 Change in Population by 10-Year Age Bracket, in millions 2005-30 2030-50 +145 m (11%) -50 m (-4%) +204 m (+142%) +90 m (26%) 40 to 59 +84 m (+26%) -63m (-15%) 20 to 39 -81 m (-18%) -26m (-7%) Under 20 -61 m (-15%) -50 m (-15%) 60 and Over -100 -50 0 50 100 150 -100 -50 0 50 100 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast These “change histograms” show the change in population by age bracket. They represent the change between the histograms shown in Chart 4. The graph on the left shows the change from 2005 to 2030, and the one on the right shows the change from 2030 to 2050. From 2005 to 2030, the total population is expected to grow by 145 million, an 11% increase. All of the gain occurs in the older age brackets, while population in the younger age groups will shrink. Over the coming 25 years, the number of young people under 20 will shrink by 15% and the number of younger working-age people will shrink by 18%. This general pattern continues over the period from 2030 to 2050 and moves up the age histogram: All of the brackets from age 0 to 60 will lose people, while the age group 60 and above will have a 26% gain, adding 90 million people. The total population will decrease by 50 million. Page 8 Workforce Implications: Workforce Growth by Age Bracket The workforce will rapidly age as the number of young workers declines. 9 Change in Working-Age Population, in millions 80 60 40 Older workers, age 40-64 20 0 -20 Younger workers, age 20-39 -40 -60 2000 -05 2005 -10 2010 -15 2015 -20 2020 -25 2025 -30 2030 -35 2035 -40 2040 -45 2045 -50 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast The population in the younger working-age brackets, age 20-39, is projected to steadily decline leading to a rapid aging of the remaining workforce. As the population ages, the number of people in the older working-age bracket of 40-64 will increase, but beginning in 2030, the size of that age group also begins to decline. Page 9 Workforce Implications: Economically Active Population The shift to older workers will continue: by 2020, older workers will comprise over a third of the active labor force. 10 Economically Active Population, in millions 800 38% 28% 700 600 45-64 year olds 500 23% 400 300 20-44 year olds 200 100 0 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 Source: ILO, Fifth Edition, 1980-2020 Labor force participation is lower for women, especially after age 45. 11 2005 Economically Active, participation rate by age 100% Men 80% 60% Women 40% 20% 0% 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65+ Source: ILO, Fifth Edition The previous charts showed data for the number of "potential workers," the total population in the working-age brackets. In reality, the "actual" number of workers is significantly less because not everyone of working age participates in the labor force. The charts in this section show ILO estimates of the "economically active" population. Chart 10 shows that the shift to older workers will continue. By 2020, workers age 45 to 64 will account for 38% of the labor force ages 20-64, up from 23% in 1980 and 28% in 2005. The share will increase as the potential number of young workers continues to decline. As shown in chart 11, labor force participation is lower for women than men at almost all ages, with participation dropping off sharply at age 45. For men the drop in labor force participation occurs at age 60. These patterns reflect the "official retirement ages" for those limited number of workers who have retirement coverage. The ILO projects that these participation rates will remain relatively steady through 2020. Page 10 Workforce Implications: Economically Active Population Increased labor force participation, especially among women and older people, could boost the labor supply. 12 Total and Economically Active Population; % Economically Active 2005 Economically Active 2020 65 and Over 94 million women 45-64 outside the labor force 59 million women 45-64 outside the labor force 45 to 64 20 to 44 88% 55% 87% 54% 96% 90% 96% 90% Under 20 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 Population in millions by five-year age bracket; males on left, females on right; ILO data for economically active population age 65+ is included in 65-69 bracket. Source: ILO, Fifth edition, 1980-2020, and UN 2006 for population <15 and 65+ The double histogram in chart 12 illustrates the gap between the total population in each age bracket and those who are actually economically active. The outer histogram is the total population and the inner histogram reflects the size of the economically active population. Labor force participation rates are high (96% for men and 90% for women) for the younger age brackets. But for the older working-age brackets, 45 to 64, the participation rate falls to 88% for men and just 55% for women. Thus, in 2005, 59 million women age 45-64 were outside the labor force. By 2020, this number will be 94 million. The double histogram illustrates the possibilities for increasing labor supply in the face of a shrinking number of potential workers: Increase the participation rate at each age (increase width of the light blue bars) Extend the definition of working age (raise the height of the light blue area) Most Chinese do not have retirement benefits and must rely on personal savings or family to support them in old age. Pension coverage is largely limited to urban workers in state owned enterprises where the official retirement age is 60 for men and 55 or below for women, ages that were set when life expectancy was closer to 50. Given today's life expectancy, these "official retirement ages," would result in about 19 years in retirement for men and 26 for women. Page 11 Workforce Implications: Demographic Dividend The fast-growing Asian economies benefitted from a “demographic dividend” – a steep run-up in workers per dependent. 13 Ratio of Working-Age Population (15-64) to Dependent-Age Population (65+) 3.0 2.5 2.0 India 1.5 China 1.0 South Korea Japan 0.5 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast A key determinant of a country's economic potential is growth in the relative size of its working-age population, specifically, the size of its working-age population relative to its dependent population, including children and retirees. The economic boost from an increase in the share of potentially productive people has been called a "demographic dividend." China has been enjoying a demographic dividend since around 1975. The increase in workers per dependent will continue until around 2015, so China has only a few years left to capitalize on this dividend. After that, the working age population begins to shrink while the older dependent population increases. Page 12 Workforce Implications: Worker-to Retiree Ratios The steep decline in workers per retiree will be especially burdensome for low-income countries such as China. 14 Ratio of Working-Age Population (15-64) to Retirement-Age Population (65+) 20 India 15 South Korea China 10 Japan 5 US 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast Raising the working age would spread the growing retirement burden among more workers. 15 Ratio of Working-Age Population to Retirement-Age Population 16 14 Working Age = 15-69 12 10 Working Age = 15-64 8 6 Working Age = 15-59 4 2 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast The number of potential workers per retiree will fall precipitously worldwide over the next 45 years—there will be fewer and fewer workers per retiree everywhere. In China the number of potential workers per retiree will drop from 9.2 to 2.6. The fiscal implications of declining worker-retiree ratios are enormous: absent huge productivity gains, economic output will be lower and fewer and fewer workers will be contributing to the support of each retiree. The declining number of workers per retiree will increasingly strain national budgets as fewer and fewer workers fund the pension and health care costs of an increasing number of retirees. The ratios shown on the graph are based on standard historical definitions of working age, 15 to 64, and retirement age, 65+. For China, the narrower definition of working age as 15 to 59 makes the declining support ratio even more threatening. With this definition, the potential support ratio shown by the green line will fall from 6 to 2 by 2050. However, extending the working age definition to 69 and retirement to 70+ would ease the fiscal burden posed by the increasing older population. In this case, shown by the blue line, the support ratio would be significantly higher. Page 13 Urbanization The rapid shift toward a predominantly urban population presents enormous challenges and opportunities. 16 Urban and Rural Population, in millions 1,600 1,400 40% urban 2005 73% urban 2050 1,200 1,000 Urban 800 600 400 200 Rural 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Source: UN World Urbanization Prospects, 2007 Revision By 2050, 73% of China's population of 1.4 billion people will live in urban areas. By 2050, the urban population in China will reach 1 billion, almost twice the number in 2005. With a doubling of the urban population, the cities in China will face enormous challenges in providing services and maintaining infrastructure. At the same time, the decline in rural population will pose the challenge of maintaining living standards and social services in those areas. Page 14 Reference Appendix A: Alternative Fertility Scenarios Appendix B: Comparative Reference – India, South Korea, Japan, and U.S. Page 15 Appendix A – Alternative Fertility Scenarios The United Nations presents four major projections for each country. The primary variable in the alternative variants is fertility rate. The specific fertility assumptions from the World Population Prospects 2006 Revision are listed below. The data used in this report are based on the Medium variant projection. Fertility assumptions: • Low: the fertility rate continues to fall until it stabilizes at 1.35 births per woman in 2020 • Constant: the fertility rate remains constant at the 2005 level of 1.70 births per woman • Medium: the fertility rate increases to 1.85 births per woman in 2020 and then stabilizes • High: the fertility rate increases to 2.35 births per woman in 2020 and then stabilizes Observations: The median age projections range from 51 for the low fertility variant (the most rapid aging) to 39 for the high fertility variant. The projections for % 65+ range from 28% to 20%, and the potential support ratios range from 2.2 to 2.9 in the high fertility case. All but the high fertility case result in declining total population. If the fertility rate declines to 1.35, by 2050 the median age will increase by 19 years to 51 and 28% of the population will be over 65. The potential support ratio of workers to retirees will drop to 2.2 from the current 9.3. If fertility rates remain constant, the share of 65+ will increase to 25%by 2050 and the potential worker to retiree ratio will fall to 2.4 from the current 9.3. The median age will increase to 47. In the medium variant used in this report, the fertility rate increases to 1.85 and median age increases to 45. The share of 65+ will increase to 24%by 2050 and the potential worker to retiree ratio will fall to 2.6 In the high fertility rate scenario, by 2050 the median age will increase by only 6 years to 38.7; 20% of the population will be 65 or older, and the ratio of working-age to retirement-age people will be 2.9. The high fertility variant is the only case that produces a growing population. Page 16 Appendix A – Alternative Fertility Scenarios 2005 Low 2030 32.5 Fertility rate = 1.35 80 40 0 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 40 80 1.316 b 7.6% 9.3 2050 43.5 80 40 0 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 40 80 1.359 b 17.4% 4.0 51.2 80 40 0 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 40 80 1.202 b 27.8% 2.2 Constant Fertility rate = 1.70 32.5 80 40 0 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 40 80 1.316 b 7.6% 9.3 42.0 80 40 0 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 40 80 1.426 b 16.6% 4.0 47.2 80 40 0 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 40 80 1.336 b 25.0% 2.4 Medium Fertility rate = 1.85 32.5 80 40 0 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 40 80 1.316 b 7.6% 9.3 41.3 80 40 0 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 40 80 1.458 b 16.2% 4.2 45.0 80 40 0 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 40 80 1.409 b 23.7% 2.6 High Fertility rate = 2.35 32.5 80 40 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 0 40 80 1.316 b 7.6% 9.3 38.8 80 40 0 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 40 80 1.563 b 15.1% 4.2 38.7 80 40 Total pop: % 65+: W/R: 0 40 80 1.647 b 20.1% 2.9 Page 17 Appendix B – Comparative Reference Fertility rates have plummeted, with especially steep drops in China and South Korea. Fertility (Births per Woman) 7 6 India 5 South Korea 4 US China 3 Replacement rate = 2.1 Japan 2 1 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast Longevity gains have occurred everywhere. Life Expectancy at Birth, in years 90 80 US 70 Japan 60 South Korea China 50 India 40 30 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast Page 18 Appendix B – Comparative Reference Growth in the working-age population will slow everywhere; absolute declines will occur in China, Korea, and Japan. Percent Change in Working-Age Population (15-64), 2005-50 India Workforce growth will slow US China So. Korea Workforces will shrink 2005-30 2030-50 Japan -50% -30% -10% 10% 30% 50% Source: United Nations 2006 medium variant forecast Page 19 Appendix B – Comparative Reference Median Age 33 China 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 41 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 2005 1.313 billion 2030 1.458 billion 24 32 India 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 2005 1.134 billion 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 80 2030 1.506 billion 45 80 60 40 20 100+ 90-94 80-84 70-74 60-64 50-54 40-44 30-34 20-24 10-14 0-4 0 20 40 60 80 2050 1.409 billion 39 80 60 40 20 100+ 90-94 80-84 70-74 60-64 50-54 40-44 30-34 20-24 10-14 0-4 0 20 40 60 80 2050 1.658 billion Page 20 Appendix B – Comparative Reference Median Age 42.9 Japan 6 4 2 0 2 4 52.1 6 6 4 2 2005 127.9 million South Korea 3 2 35 2 1 0 1 10 5 0 5 6 6 4 2 2 2005 299.8 million 2 3 3 2 1 0 1 15 10 5 0 5 6 2 100+ 90-94 80-84 70-74 60-64 50-54 40-44 30-34 20-24 10-14 0-4 54.9 3 3 2 1 0 1 2 3 2050 42.3 million 39.1 15 4 100+ 90-94 80-84 70-74 60-64 50-54 40-44 30-34 20-24 10-14 0-4 2050 102.5 million 2030 48.4 million 10 0 48.1 36 United States 4 2030 118.3 million 2005 47.9 million 15 0 54.9 10 2030 366.2 million 41.1 15 15 10 5 0 5 10 100+ 90-94 80-84 70-74 60-64 50-54 40-44 30-34 20-24 10-14 0-4 15 2050 402.4 million Page 21 The Global Aging Program at the Stanford Center on Longevity focuses on the economic and political implications of longevity. The program specifically addresses the risks and opportunities of differential population aging around the world and the impacts on global economics, sustainability, and US national security interests. The Stanford Center on Longevity seeks to transform the culture of human aging using science and technology. Working as a catalyst for change, the Center identifies challenges associated with increased life expectancy, supports scientific and technological research concerning those challenges, and coordinates efforts among researchers, policymakers, entrepreneurs, and the media to find effective solutions. SCL was founded in 2006 by Professor Laura Carstensen and received its initial funding from Richard Rainwater. The SCL Advisory Council includes George Shultz, former U.S. Secretary of State, and Jack Rowe, former Chairman and CEO of Aetna. Adele Hayutin, Ph.D., Senior Research Scholar and Director of SCL's Global Aging Program, is a leader in the field of comparative international demographics and population aging. Dr. Hayutin combines broad knowledge of the underlying data with the ability to translate that data into practical easy to understand language and implications. She has developed a comparative international perspective that highlights surprising demographic differences across countries and illustrates the unexpected speed of critical demographic changes. Previously she was director of research and chief economist of the Fremont Group (formerly Bechtel Investments) where she focused on issues and trends affecting business investment strategy. Dr. Hayutin received a BA from Wellesley College and a Master's in Public Policy and a Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley. Stanford Center on Longevity 616 Serra Street th Encina Hall, East Wing, 5 Floor Stanford University Stanford, California 94305 http://longevity.stanford.edu/myworld 650-736-8643