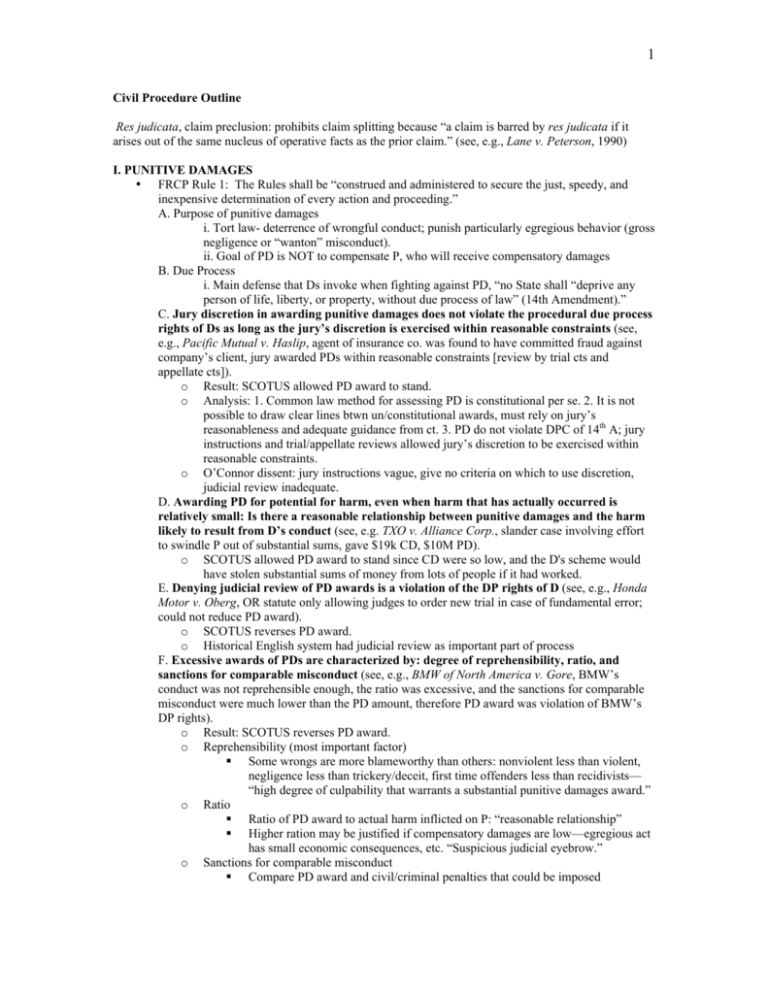

Civil Procedure Outline Res judicata, claim preclusion

advertisement