Regulatory Responses to Climate Change

REGULATORY RESPONSES TO CLIMATE CHANGE

AMERICAN COLLEGE OF REAL ESTATE LAWYERS

Boston, Massachusetts

October 2014

Katharine E. Bachman, Esq.

1

Wilmer Hale LLP

I.

Introduction

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, leaving 1,833 dead and causing $108 billion in property damage. Katrina was the costliest storm in U.S. history, and 2012 brought a close second: Superstorm Sandy caused $65 billion in damage as it tore through 24 states, leaving 160 dead and 6 million without power, and sending a 13-foot storm surge through Battery Park in

Lower Manhattan.

While no single weather event can be attributed to climate change, these and other disasters have awakened state and local officials across the country to the urgent need to address the growing threat posed by our changing climate. This article will address the regulatory responses governments have embraced to tackle climate change, including efforts to mitigate climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and to adapt to potentially unavoidable consequences of climate change by building our cities to be more resilient to future disasters. a.

Climate Change: The Evidence and the Impacts

According to the most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

(IPCC), a group of 1,300 independent scientific experts gathered under the auspices of the

United Nations, “[w]arming of the climate is unequivocal” and unprecedented changes are already occurring.

2

Climate change is expected to cause a variety of potentially devastating effects worldwide, from more severe storms, to worsening droughts, to deadlier and more frequent heat waves.

The dangers facing the United States vary greatly by region. The Southwest faces worsening droughts and heightened risk of wildfire.

3

The greatest danger to states in the Northeast and

Southeast is flooding as a result of sea level rise and increasingly severe storms, as well as more

4 frequent and severe heat waves.

These dangers are far from speculative. We are already beginning to experience many of the early effects of climate change, such as torrential rains and

1

Assisted by Alison McKinney and Samantha Rothberg of Wilmer Hale LLP

2

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2013: The

Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change (2013), available at http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/report/WG1AR5_SPM_FINAL.pdf.

3

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Climate Impacts in the Southwest , EPA.

GOV , http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/impacts-adaptation/southwest.html (last updated Sept. 9, 2013).

4

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Climate Impacts in the Northeast , EPA.

GOV , http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/impacts-adaptation/northeast.html (last updated Sept. 9, 2013); U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency, Climate Impacts in the Southeast , EPA.G

OV , http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/impacts-adaptation/southeast.html (last updated Sept. 9, 2013).

1

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

flooding in the Northeast, severe drought in the southwest, and unusually high temperature across the country. For example, the number of heat waves nationwide in 2011 and 2012 was nearly triple the long-term average,

5

and the percentage of annual precipitation falling in heavy downpour events has increased by 71% in the Northeast and 37% in the Midwest.

6

According to the United States’ 2014 National Climate Assessment, “[c]limate change, once considered an issue for a distant future, has moved firmly into the present.”

7

The primary driver of climate change is the increased concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere as a result of human activity.

8

Greenhouse gases prevent the heat that radiates from the Earth from escaping into space, keeping these gases trapped in the atmosphere where they contribute to a global warming effect.

9

According to the IPCC, atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide, the most common greenhouse gases, have “increased to levels unprecedented in the last 800,000 years,” primarily as a result of human activity.

10

Fossil fuel combustion and other industrial activities have raised atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide from 280 parts per million (ppm) to 391 ppm in the past 150 years.

11

In the United States, a significant percentage of the greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change are directly or indirectly produced by the building sector. b.

Buildings and Climate Change

Residential and commercial buildings are responsible for approximately 33% of total U.S.

12 greenhouse gas emissions.

However, they are only directly responsible for the 10% of emissions that result from fossil fuel combustion for heating and cooking needs, organic waste sent to landfills, wastewater treatment plants, and the release of fluorinated gases used in refrigerators and air conditioners.

13

The remainder represents electricity-sector emissions resulting from electricity consumption in residential and commercial buildings.

14

As the numbers illustrate, “[e]missions from commercial and residential buildings … increase substantially when emissions from electricity are included, due to their relatively large share of electricity consumption.”

15

5

Jerry M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and Gary W. Yohe eds., Highlights of Climate Change Impacts in the

United States: The Third National Climate Assessment 24, U.S.

G LOBAL C HANGE R ESEARCH P ROGRAM (2014), available at http://nca2014.globalchange.gov/downloads.

6

Jerry M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and Gary W. Yohe eds., Climate Change Impacts in the United States:

The Third National Climate Assessment 37, U.S.

G LOBAL C HANGE R ESEARCH P ROGRAM (2014), available at http://nca2014.globalchange.gov/downloads.

7

Justin Gillis, U.S. Climate Has Already Changed, Study Finds, Citing Heat and Floods , N.Y.

T IMES (May 6, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/07/science/earth/climate-change-report.html.

8

See , e.g.

, NASA, Global Climate Change: Causes – A Blanket Around the Earth , NASA.

GOV , http://climate.nasa.gov/causes (last visited June 15, 2014).

9

Id.

10

11

IPCC, Summary for Policymakers , supra

12

Id.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Electricity Sector Emissions ,

EPA.

GOV , http://epa.gov/climatechange/ghgemissions/sources/electricity.htmlhtml (last updated Apr. 17, 2014).

13

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Commercial and Residential

Sector Emissions , EPA.

GOV , http://epa.gov/climatechange/ghgemissions/sources/commercialresidential.html (last updated Apr. 17, 2014).

14

15

Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Electricity Sector Emissions , supra

Id.

2

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

According to the EPA, the building sector consumes 41% of the energy used in the United

States. Furthermore, total primary energy consumption is expected to increase by 17% over 2009 levels by 2025, fueled primarily by concomitant growth in population, households, and commercial floor space.

16

Buildings also accounted for 72% of total U.S. electricity consumption in 2006, and this number is projected to rise to 75% by 2025.

17

The U.S. Green Buildings

Council estimates that if half of all new commercial buildings were built to be 50% more energy efficient, the United States would emit six million fewer metric tons of carbon dioxide annually – the equivalent of keeping one million cars off the road each year.

18 c.

Government Responses to Climate Change

The most significant federal action to address climate change has come from the executive branch. In June 2014, President Barack Obama announced a proposed regulation that will cut

19 carbon pollution form power plants by 30 percent from 2005 levels by 2030, and in 2012, the

Obama administration finalized ambitious clean cars standards that will cut greenhouse gas emissions from cars and light trucks in half by 2025.

20

However, despite the serious threats posed by climate change, the federal government’s overall response has been lackluster at best.

Congress has repeatedly failed to pass comprehensive climate change legislation.

21

In fact,

California youth groups recently filed suit against the U.S. government under the public trust doctrine for failing to address the climate change crisis, but the case was subsequently dismissed.

22

In the absence of a comprehensive federal climate change policy, states and cities have taken the lead, adopting a two-pronged approach: mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation measures focus on reducing carbon emissions to help prevent the worst effects of climate change. Adaptation measures, on the other hand, aim to make communities more resilient to those impacts of climate change that are likely inevitable. This article will focus on mitigation and adaptation measures that relate primarily to buildings and land use, although vehicles, power plants and heavy industry are also common targets of regulation.

II.

Climate Change Mitigation: Tools to Reduce Carbon Emissions

16

U.S.

D EPARTMENT OF E NERGY , 2011 B UILDINGS E NERGY D ATA B OOK 22 (2011), available at http://btscoredatabook.eren.doe.gov/default.aspx (last visited June 15, 2014).

17

FAQ: How Do Buildings Affect Natural Resources: Buildings and Their Impact on the Environment: A Statistical

Summary , EPA.

GOV (Apr. 22, 2009), http://www.epa.gov/greenbuilding/pubs/gbstats.pdf .

18

The Dollars and Sense of Green Retrofits , D ELOITTE & T OUCHE LLP (2008), http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-

UnitedStates/Local%20Assets/Documents/us_re_Dollars_Sense_Retrofits_190608_.pdf

19

Coral Davenport and Peter Baker, Taking Page from Health Care Act, Obama Climate Plan Relies on States , N.Y.

T IMES (June 2, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/03/us/politics/obama-epa-rule-coal-carbon-pollutionpower-plants.html.

20

Obama Administration Finalizes Historic 54.5 MPG Fuel Efficiency Standards , W HITE H OUSE .

GOV (Aug. 28,

2012), http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2012/08/28/obama-administration-finalizes-historic-545-mpgfuel-efficiency-standard

21

Coral Davenport, Political Rifts Slow U.S. Efforts on Climate Laws , N.Y.

T IMES (Apr. 14, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/15/us/politics/political-rifts-slow-us-effort-on-climate-laws.html

22

Alec L. v. McCarthy , No. 13-5192, slip op. at 1 (D.C. Cir. June 5, 2014); see also Simon Davis-Cohen, Youth Are

Taking the Government to Court Over its Failure to Address Climate Change , T HE N ATION (Apr. 25, 2014), http://www.thenation.com/blog/179533/can-ancient-doctrine-force-government-act-climate-change#.

3

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

Residential, public and commercial buildings pose an attractive target to state and local governments trying to reduce energy consumption and slash greenhouse gas emissions. Most governments focus on two primary policy tools: energy efficiency measures and clean energy measures. Energy efficiency measures encourage and, in some cases, require property owners to take steps to reduce the amount of energy consumed by their building. Clean energy measures generally involve programs to encourage property owners to install clean energy facilities, such as solar panels or wind turbines.

While states and cities have adopted a diverse array of policy mechanisms to further their energy efficiency and clean energy goals, several have become increasingly common: green building codes, energy use disclosure programs, expedited permitting and preferential zoning, heightened efficiency standards for public buildings, energy efficiency and clean energy incentive programs, and community certification programs. a.

Green Building Codes

Building codes increase the energy efficiency of buildings by setting minimum requirements for building components such as insulation, water use, heating and cooling systems, lighting, windows, and ventilation systems.

23

Code requirements vary by region to account for climate differences and may, for example, require more insulation in very hot or cold areas to reduce energy consumption from heating and cooling systems.

24

In 2009, the federal government moved to encourage states to adopt the most recent recommended building codes by making code adoption a condition for receipt of State Energy Program (SEP) funding under the American

Recover and Reinvestment Act.

25

Perhaps as a result of that push, 44 states currently have a

26 commercial building code and 43 states have a residential building code.

Of those states, 11 have adopted the most recent commercial code and nine have adopted the most recent residential code.

27

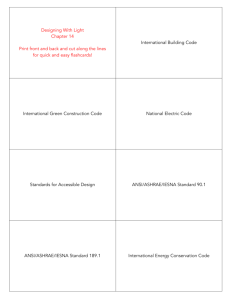

Most state and local building codes are keyed to the requirements of model building codes created by private standard-setting bodies. The two most commonly used codes are the

International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) for residential buildings, and the American

Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air Conditioning Engineers’ ASHRAE 90.1 code for commercial buildings. The IECC is promulgated by the International Code Council (ICC), a nonprofit organization that promotes building safety and performance standards.

28

Both codes are developed through a consensus-driven process in which industry experts, government officials, environmental advocacy groups, architects, engineers and academics are able to participate

23

Advanced Energy Building Codes , A MERICAN C OUNCIL FOR AN E NERGY E FFICIENT E CONOMY 1 (July 27, 2010), http://www.aceee.org/policy-brief/advanced-building-energy-codes.

24

Martha VanGeem, Energy Codes and Standards , W HOLE B UILDING D ESIGN G UIDE (2014), http://www.wbdg.org/resources/energycodes.php (last updated Mar. 24, 2014).

25

Weatherization and Intergovernmental Program , U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY 1 (June 2010), http://www1.eere.energy.gov/library/pdfs/48101_weather_arra_fsr2.pdf.

26

Status of Commercial Energy Code Adoption , U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://www.energycodes.gov/adoption/states (last visited June 17, 2014).

27

28

Id.

About ICC: International Code Council, I NTERNATIONAL C ODE C OUNCIL , http://www.iccsafe.org/AboutICC/Pages/default.ASPX (last visited June 16, 2014).

4

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

through notice and comment procedures.

29

These codes are particularly useful to state and local governments that lack the resources or expertise to develop their own building codes.

Some governments will also incorporate the requirements of the U.S. Green Building Council’s

Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification program, which imposes more stringent environmental standards than the IECC or ASHRAE codes. LEED imposes certain minimum green building requirements, such as minimum energy performance, energy and water metering, and floodplain avoidance.

30

The program also awards credits for including optional environmentally friendly features, such as installing green roofs to reduce the heat island effect.

31

LEED offers different levels of certification depending on the total number of credits a project earns, ranging from Certified (40-49 points), to silver (50-59 points), to gold

(60-79 points), and finally to platinum (80+ points).

32

Many green building codes require new buildings to be LEED certifiable and meet the criteria for LEED certification, but do not actually mandate that the buildings achieve LEED certification given the costs and uncertainties associated with the private accreditation process.

33

Below is a non-exhaustive list of states and cities that have adopted green building codes:

California:

California’s “CALGreen” Green Building Standards Code was the first statewide green building code to be adopted in the United States. The code is updated every three years. The newly adopted 2013 building code, which applies to new construction of, and additions and alterations to, residential and nonresidential buildings,

[went] into effect on July 1, 2014. CALGreen is only applicable to cities and counties if they choose to adopt its provisions, but is mandatory for all government-owned buildings and some government-regulated buildings, certain types of low-rise residential buildings, public schools and community colleges, qualified historic buildings, hospitals, and health care facilities, and regulated graywater systems. Some of CALGreen’s mandatory provisions include 20% reduction of indoor water use, compliance with energy efficiency standards set out by the California Energy Commission, and a requirement that new homes be “solar-ready.” 34

Massachusetts:

Massachusetts’ Green Communities Act requires the adoption of each new IECC edition within a year of its publication.

35

Accordingly, in 2013 the state adopted the most recent IECC and ASHRAE codes (specifically, the 2012 IECC and

ASHRAE 90.1-2010). However, the state has gone further by creating an optional

“Stretch Code” for municipalities seeking to impose more stringent energy efficiency

29

Building Energy Codes 101: An Introduction 5, U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY (Feb. 2010), www.ashrae.org/File%20Library/docLib/Public/20100301_std901_codes_101.pdf

30

U.S. Green Building Council, LEED Credit Library , USGBC.

ORG , http://www.usgbc.org/credits/mid-rise/v4 (last visited June 12, 2014).

31

U.S. Green Building Council, Heat island reduction, USGBC.

ORG , http://www.usgbc.org/node/2612275?return=/credits/mid-rise/v4 (last visited June 12, 2014).

32

33

U.S. Green Building Council, LEED , USGBC.

ORG , http://www.usgbc.org/leed (last visited June 12, 2014).

Allyson Wendt, Cities Mandate LEED But Not Certification , G REEN S OURCE ( July 30, 2008), http://greensource.construction.com/news/080730citiesmandateleed.asp

34

CALGreen Building Codes Mandatory Provisions Overview , U.S. Green Building Council, CALGreen Building

Codes Mandatory Provisions Overview (last visited June 10, 2014).

35

Building Energy Codes Program: Massachusetts , E NERGY .G

OV , https://www.energycodes.gov/adoption/states/massachusetts (last updated Jan. 16, 2014).

5

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

requirements. The Stretch Code applies to both residential and commercial buildings, and is designed to be about 30% more energy efficient than the 2006 IECC/ASHRAE 90.1-

2004.

36

New York: The Energy Conservation Construction Code of New York State (ECCCNYS

2010) establishes minimum requirements for building energy efficiency.

37

San Francisco, CA: The San Francisco Green Building Ordinance combines the 2010

38

CALGreen Building Code with stricter local requirements.

Boulder, CO: The Boulder Green Points Building Program is a mandatory green building program that requires a builder or homeowner to include a variety of sustainable building components based on the size of the proposed structure. The program covers single-family homes, multi-family residential units, and commercial buildings.

39

New York, NY: New York City’s Energy Conservation Code imposes a variety of green building and energy efficiency requirements on new construction, building additions, and substantial reconstructions of existing buildings. The regulations require all new municipal construction or major reconstruction projects to meet LEED Silver certification standards. The Code also requires all existing buildings exceeding 50,000 square feet, whether publicly or privately owned, to upgrade their lighting systems by Jan. 1, 2025, unless their systems are in compliance with the 2010 energy code or another exemption applies.

40

Dallas, TX: Dallas established its Green Building Program in 2008 and passed a citywide

Green Construction Code in 2012. The law, which was implemented in two phases, was fully effective by Oct. 1, 2013. The law offers several alternative paths to compliance: all new residential construction must either meet the minimum requirements of the city’s

Green Construction Code, or be certifiable by the standards of LEED or Green Built

Texas.

41

All new commercial construction must be compliant with the Dallas Green

Construction Code, be LEED-certifiable, and must apply for certification under LEED or

42 an equivalent green building program.

b.

Energy Use Disclosure Programs

36

Id.

37

New York Department of State, Office of Planning & Development, 2010 Energy Conservation Construction

Code of New York State http://www.dos.ny.gov/dcea/energycode_code.html

38

Green Building Ordinance , C ITY AND C OUNTY OF S AN F RANCISCO D EPT .

OF B UILDING I NSPECTION , http://sfdbi.org/green-building-ordinance (last visited June 17, 2014).

39

City of Boulder: Green Points Building Program, U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://energy.gov/savings/city-bouldergreen-points-building-program (last visited June 17, 2014).

40

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy: New York City: Energy Conservation Requirements for

Existing Buildings , U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=NY16R&re=0&ee=0 (last visited June 23,

2014).

41

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy: City of Dallas: Green Building Ordinance , U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=TX31R&re=0&ee=0 (last visited

June 23, 2014).

42

Department of Energy, City of Dallas – Green Building Ordinance (Texas) , E NERGY .G

OV , http://energy.gov/savings/city-dallas-green-buildling-ordinance-texas (last visited June 14, 2014).

6

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

Disclosure initiatives go by many names: benchmarking, reporting, and greenhouse gas inventory, to name a few. They share the common purpose of ensuring that decision-makers, property owners and tenants have access to information regarding the total energy consumption of a building, as a first step in creating a workable plan to reduce that consumption. The reporting requirement may also encourage property owners to invest in energy efficiency measures, which result in reduced operating costs. Energy-efficient operations also provide a marketing advantage for landlords, as well as the more intangible benefit of identification with socially responsible sustainability initiatives.

California: California’s Nonresidential Building Energy Use Disclosure Program imposes energy use disclosure requirements on the owners of nonresidential buildings in excess of 5,000 square feet. The disclosure duty is triggered upon the purchase, lease, financing or refinancing of the entire building. Property owners must benchmark energy use data for the building using the EPA’s Energy Star Portfolio Manager system. The information must then be released to the prospective purchaser, lessee or lender before the transaction is finalized.

43

Massachusetts: Massachusetts’ Green Communities Act requires any municipality seeking a “Green Communities” designation to establish an energy use baseline inventory for municipal buildings, vehicles, street and traffic lighting, and public utilities.

44

The

Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources (DOER) lists several tools that may be used to perform the inventory, including DOER’s MassEnergyInsight tool, the EPA’s

Energy Star Portfolio Manager, ICLEI software, or “other tools proposed by the municipality and deemed acceptable by DOER.” 45

New Jersey: New Jersey’s Clean Energy Program (NJCEP) provides free energy benchmarking services to commercial and industrial property owners. The benchmarking reports assess a building’s actual energy use relative to similar buildings, and recommend efficiency measures to improve energy performance.

46

Boston, MA: Boston’s Building Energy Reporting and Disclosure Ordinance requires large and medium-sized buildings to report their annual energy and water use to the city.

The information is then made publicly available. Furthermore, every five years buildings are required to complete an energy assessment. The energy reporting requirement is

“intended to provide information and encourage building owners and tenants to increase

43

The law specifies the timing of the disclosure: the report must be disclosed to a prospective buyer or tenant at least

24 hours before execution of the sales contract or lease, and to a prospective lender no later than the owner’s submission of the loan application. Kevin Angstenberger, Jennifer Bojorquez and Michael J. Whitton, California’s

Energy Use Disclosure Requirements for Certain Non-Residential Buildings Begins January 1, 2014 , T ROUTMAN

S ANDERS (Jan. 24, 2014), http://www.troutmansanders.com/californias-energy-use-disclosure-requirements-forcertain-non-residential-buildings-began-january-1-2014-01-24-2014/.

44

Green Communities Designation and Grant Program: Criterion 3 , M ASS . E XEC .

O FFICE OF E NERGY &

E NVIRONMENTAL A FFAIRS , http://www.mass.gov/eea/energy-utilities-clean-tech/green-communities/gc-grantprogram/criterion-3.html (last visited June 12, 2014).

45

Energy Reduction Plan (ERP) Guidance and Outline , M ASS .

D EPT .

E NERGY R ESOURCES (July 16, 2013), available for download at http://www.mass.gov/eea/energy-utilities-clean-tech/green-communities/gc-grantprogram/criterion-3.html.

46

Energy Benchmarking , N EW J ERSEY

’

S CL EAN E NERGY P ROGRAM , http://www.njcleanenergy.com/commercialindustrial/programs/benchmarking/energy-benchmarking-home (last visited June 12, 2014).

7

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

energy efficiency, reduce energy costs, and utilize incentives.”

47

The ordinance includes a compliance phase-in, requiring different classes of buildings to begin reporting in different years.

48

Municipal buildings must start reporting in 2013, non-residential buildings greater than 50,000 square feet in 2014, residential buildings greater than

50,000 square feet or 50 units in 2015, and so on.

49

New York, NY: New York City’s Greener, Greater Buildings Plan requires mandatory benchmarking for large commercial buildings, using the EPA’s free online Portfolio

Manager benchmarking tool. The objective is to give building owners and potential buyers a better understanding of a building’s energy and water consumption, eventually shifting the market towards increasingly efficient, high-performing buildings.

50 c.

Expedited Permitting and Preferential Zoning

Some states and cities encourage green building by expediting the permit process for energyefficient new construction, energy efficiency retrofits, or projects with a clean energy component. Some will also offer preferential zoning treatment for green building projects, although it is unclear how well these schemes function in practice.

Massachusetts:

The Green Communities Act requires any municipality seeking a “Green

Community” designation to enact “as-of-right” zoning for renewable energy generation, manufacturing, or research and development facilities, and to provide for expedited application and permitting processes for those facilities.

51

San Diego, CA: The Sustainable Building Expedite Program provides expedited permit processing for all eligible sustainable building projects. A more aggressive processing timeline is achieved by providing mandatory initial review meetings to facilitate early staff feedback of project proposals, significantly reducing project review timelines, and scheduling a public hearing immediately upon completion of the environmental

52 materials.

Bloomington, IN:

Bloomington’s Unified Development Ordinance offers developers certain bonuses and allowances for including features that help meet particular sustainability goals related to energy efficiency, landscape and site design, and public transportation. Incentives are based on a three-tiered system, with “bonuses” granted in accordance with the number of sustainable practices included in the projects. For example, a developer that incorporates at least two energy-efficient features could have

47

Building Energy Reporting and Disclosure Ordinance , C ITY O F B OSTON .

GOV , http://www.cityofboston.gov/eeos/reporting/ (last visited June 17, 2014).

48

Reporting: Background and Public Process , C ITY O F B OSTON .

GOV , http://www.cityofboston.gov/eeos/reporting/process.asp (last visited June 23, 2014).

49

50

Id.

PlaNYC: Green Buildings & Energy Efficiency: LL84 Benchmarking , C ITY OF N.Y., http://www.nyc.gov/html/gbee/html/plan/ll84.shtml (last visited June 17, 2014).

51

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy: Massachusetts: Green Communities Grant Program ,

U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=MA101F&re=0&ee=0/

(last updated Apr. 26, 2013).

52

Sustainable Building Expedite Program , S AN D IEGO D EVELOPMENTAL S ERVICES D EPT ., http://www.sandiego.gov/development-services/pdf/news/cp600-27.pdf (last visited June 17, 2014).

8

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

its building setback requirements decreased by six feet if the project is located in a residential district.

53

Dallas, TX: The Dallas Green Building Program establishes expedited permitting for green buildings. All applicants must provide a checklist showing the project is eligible for

LEED Silver or higher (or another approved green building standard).

54 d.

Heightened Efficiency Standards for Public Buildings

Some state and local governments set the standard for private property owners by imposing more stringent environmental requirements on government-owned buildings.

Massachusetts: In April 2007, Gov. Deval Patrick signed Executive Order 484, titled

“Leading by Example: Clean Energy and Efficient Buildings.” The order established numerous energy targets and mandates for state government buildings under control of the executive office, including:

55 o Reducing overall energy consumption at state-owned and state-leased buildings by 35% from the FY 2004 baseline by FY 2020 o Reducing state government greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2020 and by

80% by 2050 o Requiring all new construction and significant renovation projects over 20,000 square feet to meet the Massachusetts LEED Plus green building standard

Minnesota: In April 2011, Gov. Mark Dayton signed a series of Executive Orders creating a comprehensive energy savings plan for state facilities, with a goal of reducing energy use in state facilities by 20%. Each agency is required to benchmark its energy consumption and develop energy reduction goals through energy efficiency improvements and on-site renewable energy installations.

56

The state also requires the

Departments of Administration and Commerce to develop Sustainable Building Design

Guidelines for new state buildings, which are mandatory for new buildings and major renovations funded fully or in part by state bond money.

53

Sustainable Development Incentives , City of Bloomington, http://bloomington.in.gov/documents/viewDocument.php?document_id=2194 (last visited June 17, 2014).

54

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy: Texas: Dallas: Green Building Expedited Plan Review ,

U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=TX130F&re=0&ee=0/

(last visited June 17, 2014).

55

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy: Massachusetts: Energy Reduction Plan for State

Buildings , U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=MA13R&re=0&ee=0/ (last visited June 17,

2014).

56

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy: Minnesota: Comprehensive Energy Savings Plan for

State Buildings , U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=MN04R&re=0&ee=0 (last visited June 17,

2014).

9

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

New York, NY: New York City’s Energy Conservation Code requires all new municipal construction or major reconstruction projects with an estimated capital cost of more than

$2 million to meet LEED Silver certification standards.

57 e.

Energy Efficiency and Clean Energy Incentive Programs

States and cities offer a panoply of different financial incentives to encourage property owners to invest in improved energy efficiency or clean energy systems, and to help them off-set the often considerable upfront costs of doing so. These incentives can take the form of loan programs, grants and direct subsidies, financial rebates, tax exemptions and credits, and more.

One type of program deserves a special mention. Property Assessed Clean Energy (“PACE”) programs allow states and cities to provide upfront funding to property owners to make energy efficiency improvements or install clean energy capacity. The property owner then pays back the loan over time as part of their annual property tax assessment.

58

These programs have proven popular, and 25 states have both residential and nonresidential PACE programs.

59

However, they have faced some legal hurdles from federal regulators. In 2010, the Federal Housing Finance

Agency (FHFA) ordered Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac not to purchase the mortgages of properties encumbered by PACE loans, out of a concern that PACE liens have priority over mortgage liens. As a result, many states put their residential PACE programs on hold, or revised the programs to avoid threatening mortgage liens.

60

Loan Programs o Hawaii: The GreenSun Hawaii Program is a loan-loss reserve fund through which participating lenders are able to offer more favorable terms and interest rates to property owners for the installation of renewable energy and energyefficient technologies and upgrades.

61 o Illinois: Illinois business owners, non-profit organizations, and local governments seeking loans for energy efficiency and renewable energy upgrades may apply for a rate reduction under the Green Energy Loan program through the Illinois State

Treasurer’s Office, in partnership with eligible banks in the state.

o Minnesota: The Minnesota Housing Finance Agency offers an Energy Fix-Up

Loan, which provides low-interest financing for energy-efficient improvements to

57

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy: New York City: Energy Conservation Requirements for

Existing Buildings , U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=NY16R&re=0&ee=0 (last visited June 17,

2014).

58

59

What is PACE?

, PACEN OW , http://pacenow.org/about-pace/what-is-pace/ (last visited June 17, 2014).

Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, Property-Assessed Clean Energy (PACE), C2ES.

ORG , http://www.c2es.org/us-states-regions/policy-maps/property-assessed-clean-energy (last visited June 17, 2014).

60

Erika J. Sonstroem, Despite FHFA prohibitions, PACE loan programs continue to expand , L EXOLOGY (Jan. 28,

2014), http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=ed22b89a-2fa6-4d08-8e88-2a1e0ffc7fad

61

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy: Hawaii: GreenSun Hawaii , U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=HI32F&re=0&ee=0 (last visited June 17, 2014).

10

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

residential properties, such as improvements to the HVAC systems, water heaters, light fixtures, insulation and windows.

62 o Tallahassee, Florida: The city of Tallahassee offers 5% interest financing for more than 25 energy efficiency measures for residential customers. Loan repayments are made on monthly electricity or natural gas utility bills, and notes are secured with a property lien.

63

Grants and Subsidies o Illinois: The Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity provides

Efficient Living Construction Grants to Illinois-based non-profit and for-profit housing developers to include energy-efficient building practices in the rehab or new construction of affordable housing units. The grant helps offset the incremental cost of transitioning from traditional construction to energy-efficient construction.

64 o New Jersey: The Direct Install program directly covers up to 70% of the costs of installing energy efficient systems in eligible small to mid-sized commercial and industrial buildings.

65

The SmartStart Buildings program provides financial incentives for the installation of energy efficient systems and appliances in new construction projects, renovations, and equipment upgrades. Enhanced incentives are available for post-Sandy rebuilding projects.

66

Rebates and Financial Incentives o Maine: The Multifamily Efficiency Program offers building owners incentives to install energy efficiency measures in Maine’s small to medium multifamily buildings with between 5 and 20 apartment units. The program provides up to

$1,000 per unit per program year for the installation of prescribed energy saving upgrades, or up to $1,800 per unit per program year based upon the results of an energy assessment and anticipated energy savings.

67 o New York: The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority

(NYSERDA) offers two different energy efficiency incentive programs, which are funded by a systems benefit charge applied to all customer utility bills. The

Existing Facilities Program provides incentives to offset the costs of

62

Energy Fix-Up Loan , N EIGHBORHOOD E NERGY C ONNECTION , http://thenec.org/financing/Energy-FUF (last visited

June 17, 2014).

63

Energy-Efficiency Loans – Residential Customers , C ITY OF T ALLAHASSEE , http://www.talgov.com/you/youproducts-home-loans.aspx (last visited June 17, 2014).

64

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy: Illinois: Efficient Living Construction Grant , U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=IL14F (last visited June 17,

2014).

65

Direct Install , N EW J ERSEY C LEAN E NERGY P ROGRAM , http://www.njcleanenergy.com/commercialindustrial/programs/direct-install (last visited June 17, 2014).

66

NJ SmartStart Buildings , N EW J ERSEY C LEAN E NERGY P ROGRAM , http://www.njcleanenergy.com/commercialindustrial/programs/nj-smartstart-buildings/nj-smartstart-buildings (last visited June 17, 2014).

67

Multifamily Efficiency Program , E FFICIENCY M AINE , http://www.efficiencymaine.com/at-work/multifamilyprogram/multifamily-efficiency-program/ (last visited June 17, 2014).

11

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

implementing energy efficiency retrofits in existing commercial facilities across the state.

68

The New Construction Program provides technical assistance to help property owners evaluate energy-efficiency measures and incorporate new energy-efficient technologies, and provides funding to offset the additional costs associated with the purchase and installation of approved equipment.

69 o Oregon: The Energy Trust of Oregon, an independent non-profit organization, receives funding from a 3% public-purpose charge that electric utilities collect from their customers to support renewable energy and energy efficiency.

70

The

Energy Trust offers financial incentives for improvements to new residential and commercial buildings, retrofits for existing buildings, energy-efficient appliances, and manufacturing processes. The Energy Trust offers cash incentives for owners of multifamily properties to upgrade windows, appliances, heating and cooling systems, and more. The Trust also offers incentives for commercial, agricultural and institutional customers of the state utilities to increase the energy efficiency of their existing buildings.

Tax Exemptions and Credits o Florida: Florida provides a property tax exemption for residential photovoltaic systems, wind energy systems, solar water heaters, and geothermal heat pumps installed on or after Jan. 1, 2013. For the purpose of assessing property taxes on a home, an increase in the value of the property attributable to the installation of this equipment is ignored.

71 o Kentucky: Taxpayers that install certain energy efficiency measures on commercial property are entitled to a 30% state income tax credit allowable against individual, corporate or limited liability income taxes. The total tax credit may not exceed $1,000 for any combination of HVAC, hot water, and lighting systems. Kentucky also allows 30% personal tax credit for energy efficiency improvements made to the taxpayer’s principal residence.

72 o New Mexico: The Sustainable Building Tax Credit is an income tax credit created to encourage private sector construction of energy-efficient buildings for commercial and residential use. The tax credit is based on third-party validation of the building’s level of sustainability: LEED certification is required for commercial projects, and residential projects must be certified by LEED or by the

68

Existing Facilities Program Frequently Asked Questions, N.Y. S TATE E NERGY R ESEARCH & D EVELOPMENT

A UTHORITY , http://www.nyserda.ny.gov/Energy-Efficiency-and-Renewable-Programs/Commercial-and-

Industrial/CI-Programs/Existing-Facilities-Program/EFP-FAQs.aspx (last visited June 17, 2014).

69

New Construction Program , N.Y. S TATE E NERGY R ESEARCH & D EVELOPMENT A UTHORITY , http://www.nyserda.ny.gov/Energy-Efficiency-and-Renewable-Programs/Commercial-and-Industrial/CI-

Programs/New-Construction-Program.aspx (last visited June 17, 2014).

70

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy: Oregon: Energy Trust of Oregon , U.S.

D EPT .

OF

E NERGY , http://www.dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=OR05R (last visited June 17, 2014).

71

Florida Residential Solar Market Gets a Little Sunnier , C LEAN E NERGY .

ORG (May 15, 2013), http://blog.cleanenergy.org/2013/05/15/florida-residential-solar-market-gets-a-little-sunnier

72

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Energy: Kentucky , U.S.

D EPT .

OF E NERGY , http://www.dsireusa.org (last visited June 17, 2014).

12

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

Build Green New Mexico rating system. The amount of the tax credit is based on the qualified occupied square footage of the building and the sustainable building rating achieved.

73 o Texas: On Memorial Day weekend, Texas offers shoppers a sales tax holiday on purchases of certain ENERGY STAR products. Products qualifying for the exemption include air conditioners priced at $6,000 or less, refrigerators priced at

$2,000 or less, ceiling fans, incandescent and fluorescent light bulbs, clothes washers, dishwashers, dehumidifiers and programmable thermostats.

74 o Honolulu, HI: Honolulu provides a property tax exemption for the value of all alternative energy improvements. An “alternative energy improvement” means any construction or addition, alteration, modification, improvement or repair work undertaken upon or made to any building, property or land which results in (a) the production of energy from an alternative energy source (e.g. solid waste, wind, solar energy, or ocean waves), or uses a process which does not use fossil fuels, nuclear fuels or geothermal source, or (b) an increased level of energy efficiency.

75 f.

Community Certification Programs

Several states have created programs that offer financial and other forms of programmatic support for municipalities that meet certain environmental requirements.

Massachusetts:

Massachusetts’ 2008 Green Communities Act created the Green

Communities Division within the Department of Energy Resources. The Division offers financial incentives as well as educational, technical, and networking support for communities. The Green Communities Grant Program offers funding for communities investing in energy efficiency upgrades and policies, renewable energy technologies, energy management systems and services, and demand side reduction programs. To be eligible for these benefits, communities must first apply for and achieve official designation as a “Green Community,” which requires them to take several basic steps: 76 o Enact zoning ordinances to allow “as-of-right” siting for renewable energy generation, manufacturing, or research and development o Provide for expedited application and permitting processes for such facilities o Establish an energy use baseline inventory for municipal buildings, vehicles, and street and traffic lighting, and put in place a program to reduce this baseline by

20% within five years o Purchase only fuel-efficient vehicles for municipal use, when practicable

73

Sustainable Building Tax Credit , N EW M EXICO E NERGY , M INERALS AND N ATURAL R ESOURCES D EPT ., http://www.emnrd.state.nm.us/ECMD/CleanEnergyTaxIncentives/SBTC.html (last visited June 17, 2014).

74

Energy Star Sales Tax Holiday Information for Sellers , T EXAS C OMPTROLLER OF P UBLIC A CCOUNTS , http://window.state.tx.us/taxinfo/taxpubs/tx96_1331 (last visited June 17, 2014).

75

Department of Budget and Fiscal Services: Real Property Assessment Division: Exemption Forms, C ITY AND

C OUNTY OF H ONOLULU , http://www.realpropertyhonolulu.com/portal/rpadcms/Exemption?parent=FORMS&tree=forums&li=exemption

(last visited June 17, 2014).

76

Massachusetts: Green Communities Grant Program , supra

13

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

o Require all new residential construction over 3,000 square feet and all new commercial and industrial construction to minimize, to the extent feasible, the life-cycle cost of the facility by utilizing energy efficiency, water conservation and other renewable or alternative energy technologies

New York:

New York’s Climate Smart Communities certification program recognizes communities for their accomplishments relating to climate change, and rates them on a four-point scale. Communities must take actions in accordance with the climate smart pledge, such as maintaining a greenhouse gas emissions inventory, conduction a climate change vulnerability assessment, and setting government and community emissions reductions targets.

77

III.

Climate Change Adaptation: Tools to Prepare for the Unavoidable Impacts of A

Changing Climate

Local officials across the United States are already witnessing the potential dangers of a warming climate, and taking steps to counter them. The goal of climate change adaptation measures is to make communities more resilient to the potentially unavoidable effects of climate change, such as rising temperatures, increased flood risk, stronger and more frequent storms, and erratic water supplies.

Most states and communities are still in the planning stages, but the few that have begun to take more serious steps provide a potential roadmap for the future of climate change adaptation. a.

Vulnerability Assessments and Strategic Planning

According to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, 15 states have completed a climate change adaptation plan, five states have an adaptation plan in progress, and seven states have an adaptation plan recommended as part of their broader climate change action plan.

78

New York offers a representative example of how climate change adaptation planning responds to real life needs. In 2007, New York launched its “PlaNYC” long-term strategic planning initiative.

79

The program is jointly implemented by the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability (OLTPS) and the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency (ORR).

80

While climate change has been an area of focus of the plan since its inception, improving the city’s resiliency to the effects of climate change became an urgent priority in the wake of Hurricane

Sandy in 2012.

81

In 2013, the city’s newly-formed Special Initiative for Rebuilding and

Resiliency released “A Stronger, More Resilient New York,” a comprehensive report containing

257 recommended initiatives for improving the resilience of infrastructure and buildings citywide.

82

In 2014, the city released a Progress Report outlining the city’s early progress in

77

http://www.dec.ny.gov/energy/96511.html

78

State and Local Climate Adaptation , C ENTER FOR C LIMATE & E NERGY S OLUTIONS , http://www.c2es.org/us-statesregions/policy-maps/adaptation (last visited June 23, 2014).

79

80

About PlaNYC , NYC.G

OV , http://www.nyc.gov/html/planyc/html/about/about.shtml (last visited June 23, 2014).

81

Id.

82

See id.

NYC Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency, A Stronger, More Resilient New York , P LA NYC (June 11,

2013), http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/sirr/SIRR_singles_Lo_res.pdf.

14

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

meeting its goals.

84 progress.

83

Of the 257 planned initiatives, 29 have been completed and 202 are in b.

Building Code Changes

While many cities and states are still in the planning and assessment phases of climate change adaptation, a few have begun to put their plans into practice. Building codes offer an efficient mechanism for ensuring that new (and in some cases existing) construction is built to withstand future climate fluctuations.

Boston, MA: A Climate Change Preparedness and Resiliency Checklist must be submitted for all new development projects subject to Boston Zoning Article 80 review.

85

New York, NY: In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, New York City made numerous amendments to its building and zoning codes to better protect against severe storms, flooding, and other hazards: o Local Law 101/13 clarifies wind resistance requirements for building facades, and

Local Law 81/13 requires the city to complete a study on other wind risks by

2015.

86 o Local Law 83/13 requires the installation of backwater valves in flood-prone areas to prevent the backflow of sewage during flooding events.

87 o Local Law 96/13 requires the adoption of the most current and accurate flood maps available.

88 o Local Law 99/13 allows the elevation of certain building systems in flood-prone

89 areas, including telecommunications cabling and fuel storage tanks.

o In 2013, the City Council adopted the Flood Resilience Zoning Text Amendment, which modifies zoning laws to enable the use of flood-resistant construction techniques, such as using flood-resistant materials parts of buildings that are susceptible to water damage, elevating certain building types and uses above anticipated flood levels, and designing buildings to withstand the pressure of waves.

90 c.

Heightened Requirements for Public Facilities

Maryland: Gov. Martin O’Malley’s Climate Change and Coast Smart Construction

Executive Order directs all State agencies to consider the risk of coastal flooding and sea

83

PlaNYC Progress Report 2014 , P LA NYC http://www.nyc.gov/html/planyc2030/downloads/pdf/140422_PlaNYCP-Report_FINAL_Web.pdf

84

85

Id.

Climate Change Preparedness and Resiliency , B OSTON R EDEVELOPMENT A UTHORITY , http://www.bostonredevelopmentauthority.org/planning/planning-initiatives/climate-change-preparedness-andresiliency (last updated Nov. 14, 2013).

86

87

Id. at 93.

88

Id.

at 92.

89

Id.

90

Id.

Id.

See also Flood Resilience Zoning Text Amendment: Frequently Asked Questions , NYC P LANNING , http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/flood_resiliency/faq.shtml (last visited June 23, 2014).

15

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

level rise when they design capital budget projects, and charges the Department of

General Services with updating its architecture and engineering guidelines to require that new and rebuilt State structures be elevated two or more feet above the 100-year base flood level.

New York, NY: New York has initiated a number of climate change adaptation programs as part of its Special Initiative on Rebuilding and Resiliency. For example, the

Department of Parks and Recreation is developing design guidelines for facilities in coastal floodplains, expected to be released in 2015.

91 d.

Expanding Green Space

Urban forests, green roofs and other green spaces can help lessen the impact of climate change by providing shade, decreasing temperatures, and mitigating flood risk.

92

Furthermore, trees and other plants help reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by sequestering carbon dioxide.

93

A healthy tree canopy can also provide shade to buildings, which limits the need for air conditioning and reduces overall energy use.

94

Boston, MA: Boston’s “Complete Streets” and “Grow Boston Greener” programs promote green infrastructure to “reduce the urban heat island effect and mitigate flooding.”

95

Baltimore, MD:

Baltimore’s “TreeBaltimore” program aims to increase the city’s tree canopy in order to reduce the heat island effect and decrease temperatures. The city aims to achieve 40% tree canopy cover by 2030.

96

New York, NY: New York’s “Million Trees NYC” initiative is a public-private partnership aiming to plant 1 million new trees across the five boroughs.

97

The program cites climate change mitigation and adaptation as key benefits of the program, noting that urban forests help to slow climate change by sequestering carbon dioxide and reducing energy use by buildings, and also help to reduce urban temperatures by “shading buildings and concrete and returning humidity to the air through evaporative cooling.”

98 e.

Incentive Programs

Some cities and states have launched incentive programs to encourage property-owners to invest in building features that will make new and existing properties less vulnerable to climate-related

91

Id .

92

Trees and Vegetation , EPA.G

OV , http://www.epa.gov/heatisland/mitigation/trees.htm (last updated Aug. 29,

2013).

93

94

Id.

95

Id.

Preparing for Climate Change , C ITY O F B OSTON .

GOV , http://www.cityofboston.gov/climate/adaptation/ (last visited June 17, 2014).

96

97

T REE B ALTIMORE , http://treebaltimore.org/ (last visited June 17, 2014).

About Million Trees NYC , M ILLION T REES NYC, http://www.milliontreesnyc.org/html/about/about.shtml (last visited June 23, 2014).

98 NYC’s Urban Forest , M ILLION T REES NYC, http://www.milliontreesnyc.org/html/about/forest.shtml (last visited

June 23, 2014).

16

ActiveUS 130319014v.1

risks. For example, New York City’s Business Resiliency Investment Program is in the process of launching an incentive program that will “administer $110 million in funding for tenant and building owner resiliency efforts.” 99

IV.

Conclusion

States and cities are now alert to the fact that climate change is a reality, and are beginning to take the lead in efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Buildings are a major contributor to U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption, but they also have great potential to be part of the solution. Policy initiatives to track greenhouse gas emissions from buildings, impose limitations on energy consumption, and incentivize property-owners to undertake further reductions have the potential to significantly reduce emissions overall. Furthermore, adapting to the inevitable impacts of climate change requires making the buildings where we live and work resilient enough to bounce back from the worst impacts of climate change. While much remains to be done, the efforts currently underway provide a useful path toward coping with our changing climate.

99

PlaNYC Progress Report 2014 , supra

17

ActiveUS 130319014v.1