Overview of Presidential and Congressional Reconstruction

advertisement

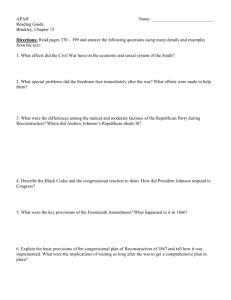

8 Additional Material: Overview of Presidential and Congressional Reconstruction With the defeat of the southern states’ attempted secession, the fundamental political issue became the terms under which they would be admitted back into the Union. Closely related to this question, however, was which branch of the federal government should set these requirements and ensure they were met. The problem first arose during the war, particularly in cases where much of a rebellious state was occupied by Union troops, such as Tennessee and Louisiana. President Lincoln tried to work with loyalists in these areas to produce new state governments to rejoin the Union. But with the main exception of West Virginia, which seceded from Virginia to become a new state in 1863, Congress did not recognize any governments formed in southern states during the war. Before the spring of 1865, the main focus of the president and the Congress was winning the war. How Lincoln would have handled Reconstruction afterwards, historians can only speculate, for on April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth assassinated him during a theatrical performance at the Ford Theater in Washington. Vice President Andrew Johnson—a War Democrat from Tennessee chosen by the Republicans in 1864 to broaden their political appeal—became the new president. His efforts to direct Reconstruction soon infuriated the Republican-dominated Congress so much that it not only ripped control of it from him, but initiated the first impeachment proceeding against a sitting president in U.S. history. The period from that May 1865 until the spring of 1867 is called Presidential Reconstruction, during which time Johnston tried to implement and defend his program, which he initially called “restoration.” Johnson allowed white southerners to reclaim their rights and property (except slaves) if they took oaths to the Union, with some exceptions. Men who had held high civilian or military rank in the Confederacy, who had been Federal officers before joining the rebellion, and who had held property exceeding $20,000, for example, would have to apply directly to the president for a pardon. While appointing provisional governors, Johnson allowed the southern states to create new governments so long as they ratified the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (which abolished slavery), nullified their ordinances of secession, and repudiated Confederate debt issued during the war. To many in the north—though not Radical Republicans—these terms seemed reasonable. But Johnson actually pardoned the vast majority of men who applied. Moreover, some states formed governments and elected representatives to Congress without abiding by © Routledge 2014 1 A d d i t i o n a l M at e r i a l : O v e r v i e w o f P r e s i d e n t i a l a n d C o n g r e s s i o n a l R e c o n s t r u c t i o n the president’s criteria: Texas and Mississippi refused to accept the 13th Amendment, and South Carolina did not revoke its secession ordinance. To the dismay of many Republicans, Johnson did not require southerners to guarantee black suffrage. Instead, in 1865–66 most southern states instituted Black Codes—sets of laws that, while acknowledging some basic rights (such as marriage), so restricted the mobility and freedoms of black people as to create a new system of white racial dominance short of outright slavery. Johnson had implemented his plan while Congress was in recess. Republican legislators were angry when they returned to Washington at the end of 1865, and became more so when committees began investigating conditions in the south and the status of freedmen and women. Congress refused to seat representatives elected from the southern states, and soon came into conflict with the president. In early 1866, for example, it overrode Johnson’s veto power to both reauthorize the Freedman’s Bureau (discussed in Chapter 8 of Ways of War) and pass the Civil Rights Act. The latter sought to protect the rights of freedmen and women, but because of the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision—which ruled that black people could never be citizens—Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment, which made all people born in the U.S. citizens with equal protection under the law. The effort to have the individual states ratify this amendment became the dominant political question in the Congressional elections of 1866. Johnson campaigned vigorously against it, both enflaming tensions with Republicans and alienating much of the northern electorate. When Congress reconvened afterwards—with large Republican majorities in both houses—it proceeded to legislate its own terms for Reconstruction. The spring of 1867 thus marks the transition from Presidential Reconstruction to Congressional Reconstruction. This was also known as Radical Reconstruction, because the program of racial equality and protection for black rights was pushed by Radical Republicans and sought sweeping changes in southern society; this program was also called Military Reconstruction. Between March and July, Congress passed three Military Reconstruction Acts, and a fourth the following year. These laws declared current southern state governments “provisional,” and stipulated Congressional requirements southern states would have to meet in order to re-enter the Union. First, eligible voters had to elect delegates to a convention that would draft a new state constitution. That constitution had to include guarantees of suffrage to all male citizens, including blacks. Once voters had ratified both the new constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, that state would be readmitted to the Union. Congress also made the U.S. Army responsible for enforcing these laws, placing the 10 unreconstructed states (Tennessee was readmitted to the Union in 1866, after it ratified the Fourteenth Amendment) into five military districts. Each one was commanded by an Army general with troops at his disposal. Congress gave these commanders authority over state governments in their districts, with responsibility for registering eligible voters, appointing and removing civilian officials, and overseeing elections and judicial ­proceedings. Having tasked the army with ensuring southern states met Congressional requirements for readmission to the Union, Republicans faced a problem in that, constitutionally, the president commanded the army. Not surprisingly, Johnson bitterly opposed the Military Reconstruction Acts, and Congress enacted them only by again overriding his veto. In early 1867, Republican legislators passed two laws to limit Johnson’s authority over the army and capacity to interfere with Congressional Reconstruction. The Tenure of Office Act stipulated that, if a federal official had been appointed with the advice and consent of the Senate (such as a member of the Cabinet), the president could not remove that appointee without the 2 © Routledge 2014 A d d i t i o n a l M at e r i a l : O v e r v i e w o f P r e s i d e n t i a l a n d C o n g r e s s i o n a l R e c o n s t r u c t i o n Senate’s consent. The particular concern here was to protect Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a Republican who supported Congressional Reconstruction. Congress also passed the Command of the Army Act, which required the president to issue all army orders through the General of the Army—Ulysses S. Grant—and not directly to any other officers. This act also prevented the president from removing this officer from his post without the Senate’s consent, and required Army headquarters to remain in Washington. Johnson viewed the Tenure of Office Act as unconstitutional, and in early 1868 fired Stanton anyway. This action precipitated his impeachment by Congress. That spring he was tried in the Senate, and came within one vote of being removed from office. In the end, some moderate Republicans worried about the precedent set if Congress removed a sitting president for what they saw as a disagreement over policy. Johnson remained president, though he no longer interfered with Congressional Reconstruction. That summer, Congress admitted six southern states back into to the Union, and the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in July 1868. The remaining states of Georgia, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia rejoined in 1870, ratifying both the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to do so. Republicans thereby successfully imposed their political criteria upon Reconstruction—but at the cost of alienating conservative southern whites who despised the Republican state governments created in the process. Events soon demonstrated that such people did not regard these governments as legitimate, or Congressional Reconstruction as the final word on the political and racial complexion of the postwar South. Figure 8.1 A group of Ute braves and squaws, Colorado. Washington, D.C.: J. F. Jarvis, publisher, c. 1893. In 1879, “civilizing” efforts by an overzealous Indian agent enraged Utes living in western Colorado. Utes had been first enemies and then allies of the U.S. in the southwestern wars of the prior quarter century. Militarily, this conflict consisted of one engagement, the Battle of Milk Creek. Utes attacked federal cavalry on September 29, 1879, and then besieged them until reinforcements arrived. The U.S. army then concentrated hundreds of troops for a major campaign before negotiations induced the warriors to cease fighting. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Stereograph Cards [LC-USZ62–110874]. © Routledge 2014 3 A d d i t i o n a l M at e r i a l : O v e r v i e w o f P r e s i d e n t i a l a n d C o n g r e s s i o n a l R e c o n s t r u c t i o n Figure 8.2 Charles Schreyvogel painting, titled “The Silenced Warwhoop,” Burke & O’Pers, c. 1908. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [LC-USZ62–99354]. Figure 8.3 Frederic Remington’s “Troops Surprising a Camp,” c. 1907 Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [LC-USZ62–110874]. 4 © Routledge 2014 A d d i t i o n a l M at e r i a l : O v e r v i e w o f P r e s i d e n t i a l a n d C o n g r e s s i o n a l R e c o n s t r u c t i o n Figure 8.4 Frederic Remington’s “Caught in a Circle,” c. 1906 Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [LC-USZ62–77506]. Figure 8.5 Frederic Remington’s “The Last Stand,” c. 1907 Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [LC-USZ62–89878]. © Routledge 2014 5