Rituals of Magical Rain-Making in Modern and Ancient Greece: A

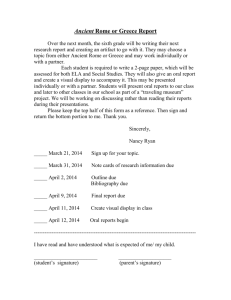

advertisement