The end of the French and Indian War in 1763 was a cause for great

advertisement

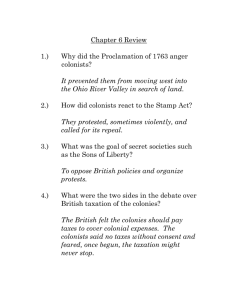

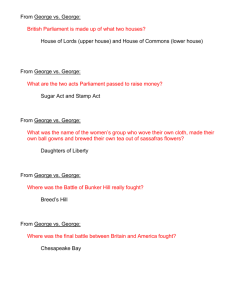

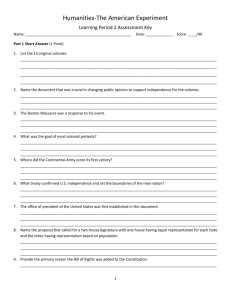

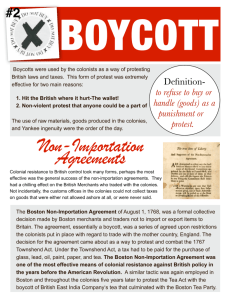

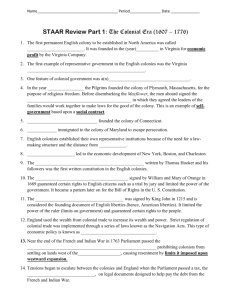

The end of the French and Indian War in 1763 was a cause for great celebration in the colonies, for it removed several ominous barriers and opened up a host of new opportunities for the colonists. The French had effectively hemmed in the British settlers and had, from the perspective of the settlers, played the "Indians" against them. The first thing on the minds of colonists was the great western frontier that had opened to them when the French ceded that contested territory to the British. The royal proclamation of 1763 did much to dampen that celebration. The proclamation, in effect, closed off the frontier to colonial expansion. The King and his council presented the proclamation as a measure to calm the fears of the Indians, who felt that the colonists would drive them from their lands as they expanded westward. Many in the colonies felt that the object was to pen them in along the Atlantic seaboard where they would be easier to regulate. No doubt there was a large measure of truth in both of these positions. However the colonists could not help but feel a strong resentment when what they perceived to be their prize was snatched away from them. The proclamation provided that all lands west of the heads of all rivers which flowed into the Atlantic Ocean from the west or northwest were off-limits to the colonists. This excluded the rich Ohio Valley and all territory from the Ohio to the Mississippi rivers from settlement. This first Quartering Act was given Royal Assent on May 3, 1765, and provided that Great Britain would house its soldiers in American barracks and public houses, as by the Mutiny Act of 1765, but if its soldiers outnumbered the housing available, would quarter them "in inns, livery stables, ale houses, victualing houses, and the houses of sellers of wine and houses of persons selling of rum, brandy, strong water, cider or metheglin", and if numbers required in "uninhabited houses, outhouses, barns, or other buildings." Colonial authorities were required to pay the cost of housing and feeding these troops. When 1,500 British troops arrived at New York City in 1766 the New York Provincial Assembly refused to comply with the Quartering Act and did not supply billeting for the troops. The troops had to remain on their ships. With its great impact on the city, a skirmish occurred in which one colonist was wounded following the Assembly's refusal to provide quartering. The Stamp Act 1765 (short title Duties in American Colonies Act 1765; 5 George III, c. 12) imposed a direct tax by the British Parliament specifically on the colonies of British America, and it required that many printed materials in the colonies be produced on stamped paper produced in London, carrying an embossed revenue stamp. These printed materials were legal documents, magazines, newspapers and many other types of paper used throughout the colonies. Like previous taxes, the stamp tax had to be paid in valid British currency, not in colonial paper money. The purpose of the tax was to help pay for troops stationed in North America after the British victory in the Seven Years' War. The British government felt that the colonies were the primary beneficiaries of this military presence, and should pay at least a portion of the expense. The Townshend Acts were a series of acts passed beginning in 1767 by the Parliament of Great Britain relating to the British colonies in North America. The acts are named after Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who proposed the program. Historians vary slightly in which acts they include under the heading "Townshend Acts", but five laws are often mentioned: the Revenue Act of 1767, the Indemnity Act, the Commissioners of Customs Act, the Vice Admiralty Court Act, and the New York Restraining Act. The purpose of the Townshend Acts was to raise revenue in the colonies to pay the salaries of governors and judges so that they would be independent of colonial rule, to create a more effective means of enforcing compliance with trade regulations, to punish the province of New York for failing to comply with the 1765 Quartering Act, and to establish the precedent that the British Parliament had the right to tax the colonies. The Townshend Acts were met with resistance in the colonies, prompting the occupation of Boston by British troops in 1768. Charles Townshend The Boston Massacre, known as the Incident on King Street by the British, was an incident on March 5, 1770, in which British Army soldiers killed five civilian men and injured six others. British troops had been stationed in Boston, capital of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, since 1768 in order to protect and support crown-appointed colonial officials attempting to enforce unpopular Parliamentary legislation. Amid ongoing tense relations between the population and the soldiers, a mob formed around a British sentry, who was subjected to verbal abuse and harassment. He was eventually supported by eight additional soldiers, who were subjected to verbal threats and thrown objects. They fired into the crowd, without orders, instantly killing three people and wounding others. Two more people died later of wounds sustained in the incident. Boston Massacre grave marker. It reads: The Remains of SAMUEL GRAY SAMUEL MAVERICK JAMES CALDWELL CRISPUS ATTUCKS and PATRICK CARR Victims of the Boston Massacre March 5th 1770 were here interred by order of the Town of Boston. The Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773, took place when a group of Massachusetts Patriots, protesting the monopoly on American tea importation recently granted by Parliament to the East India Company, seized 342 chests of tea in a midnight raid on three tea ships and threw them into the harbor. This action, part of a wave of resistance throughout the colonies, had its origin in Parliament's effort to rescue the financially weakened East India Company so as to continue benefiting from the company's valuable position in India. The Tea Act (May 10, 1773) adjusted import duties in such a way that the company could undersell even smugglers in the colonies. The company selected consignees in Boston, New York, Charleston, and Philadelphia, and 500,000 pounds of tea were shipped across the Atlantic in September. Under pressure from Patriot groups, the consignees in Charleston, New York, and Philadelphia refused to accept the tea shipments, but in Boston, the chosen merchants (including two of Governor Thomas Hutchinson's sons as well as his nephew) refused to concede. The first tea ship, Dartmouth, reached Boston November 27, and two more arrived shortly thereafter. Meanwhile, several mass meetings were held to demand that the tea be sent back to England with the duty unpaid. Tension mounted as Patriot groups led by Samuel Adams tried to persuade the consignees and then the governor to accept this approach. On December 16, a large meeting at the Old South Church was told of Hutchinson's final refusal. About midnight, watched by a large crowd, Adams and a small group of Sons of Liberty disguised as Mohawk Indians boarded the ships and jettisoned the tea. To Parliament, the Boston Tea Party confirmed Massachusetts's role as the core of resistance to legitimate British rule. British Parliament, outraged by the Boston Tea Party and other blatant acts of destruction of British property, enacted the Coercive Acts, also known as the Intolerable Acts, in 1774. The Coercive Acts closed Boston to merchant shipping, established formal British military rule in Massachusetts, made British officials immune to criminal prosecution in America, and required colonists to quarter British troops. The colonists subsequently called the first Continental Congress to consider a united American resistance to the British. In response to the British Parliament's enactment of the Coercive Acts in the American colonies, the first session of the Continental Congress convenes at Carpenter's Hall in Philadelphia. Fifty-six delegates from all the colonies except Georgia drafted a declaration of rights and grievances and elected Virginian Peyton Randolph as the first president of Congress. Patrick Henry, George Washington, John Adams, and John Jay were among the delegates. With the other colonies watching intently, Massachusetts led the resistance to the British, forming a shadow revolutionary government and establishing militias to resist the increasing British military presence across the colony. In April 1775, Thomas Gage, the British governor of Massachusetts, ordered British troops to march to Concord, Massachusetts, where a Patriot arsenal was known to be located. On April 19, 1775, the British regulars encountered a group of American militiamen at Lexington, and the first shots of the American Revolution were fired