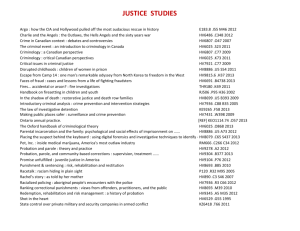

The Factors That Shape Organized Crime

advertisement