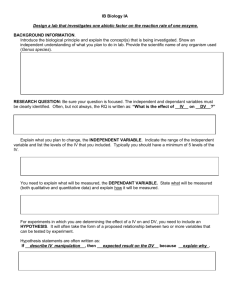

Internal Assessment

advertisement