The MUNI-

MELTDOWN

THAT WASN’T.

November 2014

SPONSORED BY

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown

2

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown

3

MUNI MANIA: A TIMELINE

FEBRUARY 2009

“If a few communities stiff their creditors

and get away with it, the chance that others will follow in their footsteps will grow.”

– Warren Buffett

APRIL 2009

Moody’s assigns the U.S. Local Government Sector a negative outlook

SEPTEMBER 29, 2009

“Dark Vision: The Coming Collapse of the

Municipal Bond Market”

– Frederick J. Sheehan, published

by Weeden & Co.

DECEMBER 2009

“Are State Public Pensions Sustainable?”

– Joshua D. Rauh

MARCH 30, 2010

“State Debt Woes Grow

Too Big to Camouflage”

– The New York Times

APRIL 15, 2010

APRIL 4, 2010

“Once a few municipalities default, there is

a risk of a widespread cascade in defaults.”

– Richard Bookstaber, blog

“This isn’t capitalism. It’s nomadic thievery.”

– “Looting Main Street,” by Matt Taibbi, Rolling Stone

SPRING 2010

SUMMER 2010

“How to Dismantle a

Muni-Bond Bomb”

– Steven Malanga, City Journal

OCTOBER 5, 2010

“Cities in Debt Turn to States,

Adding Strain”

– The New York Times

NOVEMBER 29, 2010

“Give States a Way to

Go Bankrupt”

– David Skeel,The Weekly Standard

DECEMBER 19, 2010

“Hundreds

of billions”

– Meredith Whitney, on 60 Minutes

JANUARY 20, 2011:

“Misunderstandings Regarding State Debt, Pensions,

and Retiree Health Costs Create Unnecessary Alarm”

– Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 21-page white paper

“Beware the Muni Bond Bubble: Investors are kidding themselves if they

think that states and cities can’t fail.”

– Nicole Gelinas, City Journal

SEPTEMBER 2010

“The Tragedy of the Commons”

– Meredith Whitney

NOVEMBER 16, 2010

“California will default

on its debt.”

– Chris Whalen to Business Insider

DECEMBER 5, 2010

“Mounting Debts by States

Stoke Fears of Crisis”

– The New York Times

DECEMBER 24, 2010:

“I can’t make the numbers work. If you look at the 10 largest

cities and the 25 largest counties in the country, that’s $114 billion in debt outstanding. So you gotta basically have New York,

Chicago, Phoenix, Los Angeles — these cities start to default.”

– Ben Thompson, Samson Capital, on CNBC

AUGUST 2011:

“[I don’t care about the] “stinkin’ municipal bond market.”

– Meredith Whitney to Michael Lewis

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown

4

INTRO

An old-media kind of guy, I still keep file folders of stories, blog

entries, clippings, messages and reports printed out and more or

less sorted. Back in early 2009, I started a file labeled “Hysteria’’

to hold the physical evidence of what I thought the most unusual

and even outlandish claims being leveled against an asset class I

have spent 33 years writing about — municipal bonds.

Over the next couple of years, the file swelled. I started another. And another. I didn’t

even include Meredith Whitney. She got an entire file of her own.

I collected so much material that I decided to use it as a presentation to the Bond Attorneys Winter Workshop one year. Even then I only got to use the high-points, or low

points, if you prefer, entering each exhibit into evidence. I considered this clever.

Inside

In the Beginning

Particular and Specific......................5

The Undiscovered Country

Just Look!..........................................8

The End of Something

Splendid Isolation No More...............9

‘Dark Vision’

Bombs Away...................................10

“Show me a revenue stream and I’ll show you a bond issue,” is an old banker’s axiom.

The writer’s equivalent is probably, “Show me a box of research and I’ll show you a book.”

Or, in this case, a special supplement. And so here we are.

The Coming Collapse

In Sum............................................. 11

In 2010, municipal bonds, hitherto known only as secure, boring investments, if sometimes a little weird, were front-page news. It was stated with some confidence that the

entire market was going to go bust.

Into the Abyss

‘Dump Munis’...................................12

Of the Great Municipal Market Meltdown – so confidently predicted for 2010, 2011, 2012,

and so on – I think we are now finally able to say, “That didn’t happen.” As it was being

predicted, I observed that the reason it wasn’t happening was because “that doesn’t happen.” In other words, the various “experts’’ then weighing in about state and local governments’ coming mass insolvency and/or repudiation didn’t know what they were talking

about. That didn’t stop what I termed their “Inexpert Testimony” from being offered. And

widely (and unfairly, I thought) quoted.

I define “meltdown’’ here as its proponents did: widespread default or outright repudiation

of municipal bonds. There were a number of (non-muni) analysts and observers eager to

forecast just this possibility. Others contented themselves with stoking hysteria in regard

to public pensions. One even expressed outrage over Wall Street’s underwriting and

banking relations with Main Street borrowers. The blowup to come, we were assured,

was going to be almost operatic.

The more I leafed through these bulging files — in retrospect, and recollected in tranquility, as the poet says — the more I asked, How did this come about? Why were so many

people who were little more than tourists in MuniLand taken so seriously?

Why was the opinion of those who did know what they were talking about so heavily discounted? What lessons can investors learn from this? Because lots of investors,

especially after Meredith Whitney made her famous call on “60 Minutes” in December

of 2010, sold both muni mutual fund shares and individual bonds, sometimes at fire-sale

prices. They wanted to get out at any price. Panic was in the air.

Public Pensions

We Have a Problem.........................13

Media Frenzy

Everyone’s Meltdown.......................16

The Market Responds to Its Critics

First Responders.............................19

Oh, Meredith

‘Hundreds of Billions’.......................23

After ‘Hundreds of Billions’

Victory Lap......................................24

Returning Fire

That’s Enough!.................................26

What Happened, Lessons Learned

Age of Twitter...................................27

Appendixes

To the Foregoing Work....................30

There’s no one answer. There are lots of answers.

There’s no one answer.

There are lots of answers.

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown

5

I: In the Beginning

Our story begins in 2009. There may have been hysterical commentary

about the condition of the municipal bond market before this. There

probably was; I just don’t recall it. Maybe it lacked a certain intellectual

heft, and so had little impact on me as I read it. More likely, it was submerged in the round-the-clock hysteria then surrounding nothing less

than the state of capitalism in the free world. The recession that had

begun in late 2007 and accelerated in 2008 still had a way to go.

Faced with Wall Street firms going bust,

mass firings, the housing price collapse

and 401(k) plans evaporating as the stock

market plummeted, it was hard for municipal bonds to make the front page.

They tried. Two events in particular had

rocked munis in 2008. In February, the

$330 billion auction-rate securities market

froze after Wall Street banks stopped

providing backstop bids for the stuff. The

market had long relied on a convention

the Street could no longer afford – instant

liquidity. The result: Investors in many

auction issues could see their money, but

couldn’t lay their hands on it. It would take

years to remedy the situation.

Rise of the Insurers

This was damaging enough to the market’s psyche. Even worse was the downgrade of most of the AAA-rated municipal

bond insurers. Bond insurance was perhaps the most successful franchise in the

municipal bond market, originating in 1971

and reaching a peak penetration of 57

percent of the new issue market by 2005.

Bond insurance was also the thing that

“commoditized’’ the market. No longer did

investors have to study the innumerable

details of a bond issue’s structure and

security. Now there was just this thing you

could buy called a municipal bond that

produced interest that was tax-exempt and

that was incredibly safe and secure in the

first place and was now even insured as to

repayment of principal and interest and so

rated AAA. Or so it was thought for a very

brief period stretching from perhaps 1985

to the collapse of the insurers in 2008.

The insurers had proven to be in the

right place at the right time. They were

even, helpfully, a little early. States and

municipalities were just about to embark

on a borrowing binge, spurred in part

by the threat, real and imagined, of tax

reform that would prohibit them from

financing certain things with tax-exempt

securities, and then by a decline in interest rates that sparked a wave of refinancing, and finally by a boom in what we may

term bankerly creativity. I’m sure the rise

of suburbs beyond the suburbs and their

concomitant needs for infrastructure like

streets and sewers and schools was part

of it, as was the later urban renaissance.

Analysts could take cold comfort in the

fact that the insurers didn’t lose their AAA

ratings because of anything they’d done

in the municipal market. Their sin was

expanding into asset-backed securities,

a move inspired as much by stockholder

interest in returns as demanded (well,

almost) by the ratings companies, which

urged the insurers to expand into more

lucrative areas of business.

And here it might be appropriate to say

why commoditization was so welcomed in

this market. As investor Paul Isaac once

put it to me over cocktails, “So what you’re

saying is, municipal bonds are particular

and specific to a remarkable degree.’’

Isaac was responding to my amazement and frustration trying to understand

a subject that seemed endless and

unfathomable. This was back in the early

1980s. I stole his phrase and have used it

ever since, only occasionally substituting

“insane’’ for “remarkable.’’

This turned out to be the single most

important observation about municipal

bonds I have ever heard. It explains so

much. It explains everything.

The multifarious (“of great variety;

diverse’’ according to Webster’s) nature

of municipal bonds is one of the reasons

Source: Nick Ferris/Bloomberg

Joe Mysak

I became so convinced that a national

meltdown was unlikely. We’re not talking

about dozens or scores of issuers, but

tens of thousands.

The Census of Governments done by

the U.S. Census Bureau every seven

years shows that there are just over

90,000 governmental entities in the U.S. It

has been estimated by the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board, the market’s

self-regulatory organization, that perhaps

50,000 have borrowed money in the municipal market at some time or other.

They have done so with serial and term

bonds, with notes, with variable- and the

aforementioned auction-rate securities,

using their full-faith and credit taxing

power pledge, their limited taxing power

pledge, their mere promise to appropriate

money for debt service, and more often

than not (since the 1970s), with the promise of specific revenue streams. And did I

mention the companies, like airlines, that

also borrow in the municipal market?

Sucker’s Bet

In fact, it’s a rare government that uses

its general obligation, full-faith and credit

pledge to sell bonds to borrow money.

What was once termed the shadow government, and not in an approving way, is

the primary engine of borrowing in today’s

continued on next page...

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown

6

continued from previous page...

muni market: a network of districts, agencies, authorities and public corporations,

staffed by their own professionals and

insulated, if you will, from the public and

even from duly-elected government officials, like a city council, for example. The

decentralized nature of municipal issuance turns out to be one of the market’s

great strengths.

Add to this the perpetual nature of most

governmental entities and you can see

why a mass municipal meltdown was a

sucker’s bet. Perhaps only someone who

has looked through 12 or 20 screens of

a Bloomberg terminal’s “Municipal Bond

Ticker Look Up’’ can appreciate this. Type

in a name of a municipal issuer and you

get screen after screen of apparent direct

relations. Who are all these guys? The

auction-rate freezeout and the collapse of

the bond insurers were stunning stories,

unimaginable for anyone familiar with the

things, yet in the context of the times in

2008 just more collateral damage from the

subprime mortgage implosion.

More bad news was on the way in 2009,

as the recession deepened and states

and municipalities saw tax revenue dwindle. The recession officially ended in June

of 2009. State tax collections declined

versus the same period the previous year

in every quarter from the fourth quarter

of 2008 to the fourth quarter of 2009,

according to the Nelson A. Rockefeller

Institute of Government.

That’s another feature of the municipal

market; state and local government isn’t

on the front end of recession, but on the

tail. Public finance is a lagging indicator.

This is why most states and municipalities were still hiring in 2008, even as the

private sector was shedding hundreds of

thousands of jobs.

Acronym Mad

Now we come to the first major market

“call’’ that attracted my attention as being a little exaggerated if not hysterical.

Because, let’s face it, Warren Buffett is

no hysteric.

The reference to munis came in the

February 2009 edition of the letter Buffett

sends annually to Berkshire Hathaway

shareholders. Berkshire had launched

Berkshire Hathaway Assurance Company

(or BHAC: the bond insurance business

is acronym-mad) in 2008 as a municipal

bond insurer. Under a section of his letter

entitled, Tax-Exempt Bond Insurance,

Buffett recounted BHAC’s year, which at

one point included an offer to reinsure the

other largest monoline municipal bond

insurers’ existing books of business. The

insurers rebuffed the offer.

Buffett said BHAC would “remain very

cautious about the business we write and

regard it as far from a sure thing that this

insurance will ultimately be profitable for

us. The reason is simple, though I have

If a few communities stiff their

“creditors

and get away with it, the

chance that others will follow in

their footsteps will grow.

— Warren Buffett

”

never seen even a passing reference to it

by any financial analyst, rating agency or

monoline CEO,’’ Buffett wrote.

He continued, “The rationale behind

very low premium rates for insuring

tax-exempts has been that the defaults

have historically been few. But that record

largely reflects the experience of entities

that issued uninsured bonds. Insurance of

tax-exempt bonds didn’t exist before 1971,

and even after that most bonds remained

uninsured.’’

Buffett continued: “A universe of tax-exempts fully covered by insurance would be

certain to have a somewhat different loss

experience from a group of uninsured, but

otherwise similar bonds, the only question

being how different. To understand why,

let’s go back to 1975 when New York City

was on the edge of bankruptcy. At the time

its bonds — virtually all uninsured — were

heavily held by the city’s wealthier residents as well as by New York banks and

other institutions. These local bondholders

deeply desired to solve the city’s fiscal

problems. So before long, concessions

and cooperation from a host of involved

constituencies produced a solution. Without one, it was apparent to all that New

York’s citizens and businesses would have

experienced widespread and severe financial losses from their bond holdings.’’

If, Buffett posited, all of the city’s bonds

were insured by Berkshire, would “similar belt-tightening, tax increases, labor

concessions, etc.’’ have been forthcoming? Of course not, he answered. “At a

minimum, Berkshire would have been

asked to ‘share’ the required sacrifices.

And, considering our deep pockets, the

required contribution would most certainly

have been substantial.’’

In other words, the city would have

defaulted on its insured bonds, leaving

the insurer to pay the debt service. At

some point, it is assumed, the city and the

insurer would sit down and negotiate the

terms of repayment, but not in full.

‘Simply Staggering’

Buffett observed that local governments

were going to face far tougher fiscal problems in the future. “The pension liabilities I

talked about in last year’s report will be a

continued on next page...

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown

7

continued from previous page...

huge contributor to these woes. Many cities and states were surely horrified when

they inspected the status of their funding

at year-end 2008. The gap between assets and a realistic actuarial valuation of

present liabilities is simply staggering.’’

So far, so good. New York City’s nearmiss with bankruptcy, I know, was a closerun thing, with the state playing a powerful

role in the rescue, along with the United

Federation of Teachers.

Buffett’s theory of the role insurers

might play in a meltdown was somewhat

prescient, as the Detroit bankruptcy has

shown us: the insurers have a seat at the

table, and are indeed expected to “contribute’’ to Detroit’s future, by taking less than

they are owed by the city.

Buffett’s concerns about public pensions

were nothing new or astonishing. Numerous analysts pointed out how they had suffered after the tech bubble burst only a few

years before. (It is worth noting, however,

that in 2000, the so-called funding ratios of

public pensions topped 100 percent).

And then Buffett went just a little bit further.

“When faced with large revenue shortfalls, communities that have all of their

bonds insured will be more prone to

develop ‘solutions’ less favorable to bondholders than those communities that have

uninsured bonds held by local banks and

residents. Losses in the tax-exempt arena,

when they come, are also likely to be

Municipal bonds are

“particular

and specific to

a remarkable degree.

”

– Paul Isaac, Investor

highly correlated among issuers.’’

This last sentence can be parsed any

number of ways, and I’m not going to attempt it here.

But then, this: “If a few communities stiff

their creditors and get away with it, the

chance that others will follow in their footsteps will grow. What mayor or city council

is going to choose pain to local citizens in

the form of major tax increases over pain

to a far-away bond insurer?’’

Buffett concluded that insuring municipal bonds “has the look today of a

dangerous business.’’

The headline words were “dangerous

business.’’ The real story was in the previous two sentences, about 1) a seeming

contagion in municipalities

actively seeking to stiff their creditors and

“get away with it,’’ and 2) elected officials

choosing not to make some very hard

choices.

I didn’t know it at the time, of course, but

the Buffett letter was the first salvo in what

would become a muni meltdown barrage.

At the time, I thought it interesting, purely

because munis were so unremarked upon

in general. I also thought it a trifle overwrought, said so in a column, and was

surprised at how many e-mails I received

from the Great Man’s minions, eager to

denounce unbelievers. Much worse was

to come.

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown

8

II: The Undiscovered Country

There wasn’t a lot of big press coverage of

municipal finance because editors found

the topic almost stupefyingly dull.

Everybody’s Talking

Source: Bloomberg/Daniel Acker

Warren Buffett

In 2008, Buffett made his overtures to

the beleaguered bond insurers. The possibility that they might lose their top credit

ratings was already a hot topic of conversation among market participants, not

least because investor Bill Ackman was

shorting the stock of the biggest insurer,

MBIA, and he made sure the Wall Street

Journal knew it.

But there were a lot of other things being

discussed in the municipal market, as

well. How would a decline in tax revenue

affect budgets and credit ratings? How

would states and municipalities deal with

stock market losses that had blown a hole

in the value of the assets they had put

away to cover pension liabilities? Could

they manage the expense of “Other PostEmployment Benefits,’’ previously handled

mainly as a pay-as-you-go expense?

Then there was the SEC’s ongoing investigation into bid-rigging and price-fixing

in the municipal reinvestment business,

the whole murky world that exists after

issuers sell bonds and need to invest the

proceeds. The use and proliferation and

opacity of swaps was finally getting some

attention, too.

The Municipal Securities Rulemaking

Board, for its part, was in the midst of a

push to reform disclosure and enhance

price transparency, as well as regulating municipal advisers and establishing

who owed issuers fiduciary responsibility,

among other things.

Yes, all of these topics were being discussed in the muni market. Just because

these subjects only sporadically appeared

in the major newspapers and almost

never made it to television and cable news

doesn’t mean that they weren’t being

talked about, and covered by local newspapers and the very specialized financial

press, that write about munis. There was

a lot of ferment going on in municipals in

the 2000s.

And yet, a common claim among those

who would stoke the muni meltdown

hysteria was that “nobody’s talking about

this,’’ as if an almost $3 trillion market (at

the time) was somehow being conducted

entirely in secret — and I have been a

critic of how private public finance can

sometimes be.

Or they would claim, “the experts’’ (whoever these people were supposed to be;

perhaps even I was one of them) were so

conflicted that they couldn’t possibly see

this or that self-evident truth.

The other side of the argument, of

course, is that nobody was talking about

“it’’ (whatever it happens to be), because

“it’’ isn’t true.

The mainstream media, as they call it

nowadays, has always had a problem with

the municipal market. Municipal bonds

are hard to understand. Bankers and the

many financial professionals who assist

public officials in their bond sales tend to

follow a code of silence. The sales and

trading of municipals is done over the

counter, almost on a bespoke basis.

The press loves a simple story, and

public finance is extremely nuanced. The

relatively high cost of entry for investors

(you need tens of thousands of dollars

to invest in munis, a few hundred to buy

stocks) means that municipal bonds aren’t

really even part of the financial “culture,’’ in

the way that stocks are.

Tourists in MuniLand

There wasn’t a lot of what I’ll call big

press coverage of municipal finance because editors found the topic stupefyingly

dull and so, they reasoned, few people

would care to read about it. I sometimes

think I would have had more readers if I

wrote about Hummel figurines, or numismatics, rather than munis.

Beginning in 2009, more people were

claiming that the municipal market was

the undiscovered country. Just look at

what we’ve found, these critics — tourists

in MuniLand — would say. And, no surprise, the story they so often brought back

was very similar to the stories that tourists

tell: by turns frightening and amusing, and

of limited long-term value.

Never had so many been so misled by

so few with such little actual expertise.

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown

9

III: The End of Something

The municipal market’s long period of

splendid isolation, if we can call it that,

was all about to end. The story of the

market meltdown that wasn’t is very much

a story of the media.

To repeat: Nobody was saying that

states and municipalities were not facing

some pretty stiff headwinds as a result of

the real estate bubble and recession.

What made this time different is that

house price declines played out nationally

rather than, as is usual, regionally. There

were of course some markets that fared

much better than others, but prices fell

everywhere.

In April 2009, Moody’s assigned a

negative outlook to the U.S. Local Government Sector, saying, “This is the first

time we have assigned an outlook to this

extremely large and diverse sector. This

negative outlook reflects the significant

fiscal challenges local governments face

as a result of the housing market collapse,

dislocations in the financial markets, and

a recession that is broader and deeper

than any recent downturn.’’

Note the language: “significant fiscal

challenges.’’

I had long been a fan of the restrained,

sober style the analysts at the rating companies had learned to use (it was, I was

informed, very much a learned style). If

you were unaccustomed to the style, you

could read through thousands of words of

analysts’ prose and not quite know what

they were really saying, or if they were

saying anything at all.

Not this time. The company continued,

“Sharply falling property values, contracting consumer spending, job losses, and

limited credit availability lead the long list

of developments that will make balancing

budgets in the coming year particularly

difficult. The negative outlook assigned to

the U.S. local government sector encapsulates our view on this challenging

environment and the strains that will be

evident in credit for issuers across the

industry.’’

This was a very well-crafted, detailed

piece of work in nine pages. I was impressed by the – for them – blunt tone as

well as the way it reminded its readers

that this was a big market, particular and

specific to a remarkable degree, in the

words of my friend Isaac.

Again, Moody’s: “Credit pressures faced

by local governments and their responses

to these pressures will vary significantly

across and within states due to uneven

economic conditions, differing revenue

mixes and service mandates, inconsistent

property assessment practices, and different levels of revenue raising authority. The

governance strength of individual issuers

and behaviors which demonstrates their

willingness and ability to adapt to that environment will determine the overall trend

in individual ratings.’’

The rating company put the entire sector

on negative outlook. It didn’t say that the

entire sector would respond in the same

way to the extraordinary, “unprecedented’’

pressures then accumulating: unemployment at more than 8 percent, stock prices

off 50 percent, home prices down an average 25 percent from their peak. And what

might be the result? “Increased rating

revisions’’ for local governments.

This was an extremely reasonable, clear

piece of work from a generally recognized authority on the subject. Unhappily,

because of their role in the subprime

mortgage collapse, the rating companies in

general had forfeited a certain credibility by

this point, even in the municipal market.

An earlier announcement by Moody’s in

March of 2007 that it would stop using a

dual scale to rate municipalities and corporations had touched off a controversy

that once would have dominated market

conversation. Now, in the midst of the

recession, it was almost an afterthought.

Moody’s and Fitch finally recalibrated

their ratings in 2010; Standard & Poor’s

announced a change in its own methodology for rating municipalities soon after.

Looking back at 2009, I am surprised by

just what a newsy year it was in municipals. Jefferson County, Alabama, was still

trying to avoid bankruptcy. Municipalities were starting to file lawsuits against

those Wall Street firms that had sold them

swaps and derivatives.

In August, the MSRB said it was looking

at “flipping’’ in the muni market, apparent

in glaring fashion soon after states and

municipalities started selling federallysubsidized Build America Bonds.

A federal grand jury would finally indict

CDR Financial Products, the firm at the

red-hot center of the market’s bid-rigging

scandal, at the end of October.

There was a time I used the expression “bullets don’t grow on trees’’ from the

movie “Michael Collins,’’ to characterize

actual municipal market news, and to caution reporters to husband story ideas with

care. No longer. In 2009, it seemed like

news was breaking every day.

Then one day in October, I got an e-mail

from a reader. His name was familiar to

me as someone who occasionally commented on my columns. He attached a

report that he said he found compelling.

This is the first time we have

“assigned

an outlook to this large

and diverse sector.

”

— Moody’s

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown 10

IV: ‘Dark Vision’

I wish I saved that first e-mail, so I could

give proper credit to the sender. In the

weeks to come, more correspondents

would forward me the same report, most

accompanied by a message written in a

tone of resignation and dismay. One even

sent me a copy in the mail. People wanted

to make sure I saw this thing

The report was “Dark Vision: The

Coming Collapse of the Municipal Bond

Market,’’ published by Weeden & Co. for

its clients. It was a “guest perspective’’ as

they called it, by Frederick J. Sheehan.

This was the first piece I had ever seen to

call for the municipal market’s imminent

meltdown. It was also the first piece to

demonstrate to me that the muni market

was entering a new media age.

I originally dismissed it. I glanced at that

title, winced, and put it aside. Weeden &

Co.? They weren’t in the municipal market.

Frederick J. Sheehan? Who was he? I

hadn’t seen him on the muni beat before.

“The Coming Collapse of the Municipal

Bond Market’’? Please.

It really wasn’t until I spotted it again, this

time in a reference to a business blog on

yet another financial news web site, that I

realized that the market had a problem. In

the new Internet age, anyone could write

anything and it could achieve the credibility and authority of “publication.’’

Anything Goes

And it metastasized. An article or report

was no longer published once, but again,

and again, and again, all over the Internet.

The new reporters, or editors, or whatever

you called them, sometimes did no more

than put an inviting and often sensational

headline on a short summary, and then

provide a link to the actual underlying

document, story, report, lawsuit, opinion

piece, whatever it happened to be. And

then dozens or scores of readers could

comment on it, further legitimizing the story,

no matter how inane their own commentary.

In the new Internet age, anyone could write

anything, and it could achieve the

credibility and authority of ‘publication.’

In this publication democracy, it seemed,

everything was valid, all points of view legitimate. It would take some time, for me,

to realize that the key thing in this transaction was for the author to say something,

usually bad, was going to occur, and very

soon. This seemed to be the only criterion

for the new “publication’’ world: Something Bad Is Going To Happen. This got

you clicks, this got you viewers, this got

you subscribers, this got you on television, and, in some cases, it got you book

contracts.

In fact, more often than not, in public

finance as in most people’s lives: Nothing

happens. Things muddle along, things

work out, or not, in slow and usually

unspectacular fashion. Especially, might I

add, in the municipal bond market, where

trading in a new issue typically ceases

after about 30 days, and where time is

measured with a calendar.

“The Coming Collapse of the Municipal

Bond Market’’? The timing of this piece

was propitious. The Great Recession,

it seemed, had just ended in June, but

people were still ready to believe anything

about everything. “The Coming Collapse

of the Municipal Bond Market’’? Why not?

FOLLOW JOE MYSAK ON TWITTER

FOR REGULAR UPDATES AND ADDITIONAL INSIGHTS

Hysteria Begins

“Dark Vision’’ was dated Sept. 29, 2009.

This is when I date the kickoff of the Muni

Market Meltdown Hysteria. So many

things came together at this precise moment: the rise of the Internet; the explosion of business and financial news web

sites (it is worth noting that Business

Insider only began in 2007); more cable

business coverage; the greatest recession since the Great Depression; the 24/7

news cycle.

Only a few years later, I suspect, any

such “meltdown’’ call would have been

mitigated, even refuted, by the very same

Internet that had given birth to it. Twitter

would kill it.

But in 2009, most of those who knew

anything about the municipal market

weren’t tweeting. “Bond Girl,’’ for example,

didn’t start tweeting until April of 2011,

Reuters’ Muniland blogger Cate Long in

July of 2010.

Inexpert testimony was set for a very

brief reign in the muni world.

>>>> @joemysak

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown 11

V: The Coming Collapse of the Municipal Bond Market

Source: Bloomberg/Andrew Harrer

Alan Greenspan

The most remarkable part of “Dark Vision’’

was the title and subhead. For the uninitiated,

“Dark Vision’’ looked plausible enough, with

various bits of data and almost two pages of

scholarly-looking footnotes. The more I read

it and considered it, the more I realized it was

little more than a series of assertions, without

a lot of proof.

The author had written a couple of books

critical of Alan Greenspan and the Federal Reserve, according to the identifying

note attached to the piece. I got the feeling,

as I was reading, that he was grinding a

libertarian axe. Political point of view and

credit analysis usually don’t mix well.

I don’t want to spend too much time on

“Dark Vision,’’ which I found unpersuasive, so

let me try and summarize.

It is time to get out of municipal bonds,

says Sheehan.They are now to be considered

speculative investments, and buyers are just

not being compensated enough for the risk

they are taking. Fair enough, I thought.

“The municipal market will probably repeat

the pattern of the sub-prime collapse,’’ he

wrote. “Although it is plain to see, the usual

experts do not notice.’’ He doesn’t say who

these experts are, although I infer that they

are the rating companies.

He describes the “mess’’ in public finance:

“Recent cost-cutting by states and municipalities is inadequate. This much is probably obvious. What may go unrecognized

is that filling these gaps using conventional

measures is impossible. Parties to suffer

from unconventional measures include

bondholders.’’

This pretty much sums up the Sheehan

argument. States and municipalities spend

too much, borrow too much, promise too

much to their employees. Faced with the

“impossible,’’ many municipalities will seek

bankruptcy court protection.

Bondholders can’t rely on issuers’ pledges to levy taxes to pay debt service. Nor

can they trust that the courts will ensure

that they are paid.

Had Sheehan limited his remarks to “Detroit,’’ I might have hailed him as a visionary

today. Had he somehow limited his thesis

to “some’’ or even “a handful’’ of municipalities, even that would have been somewhat

acceptable. But no. The entire market will

“collapse.’’ On the other hand, who wants

to publish “The Coming Collapse of an Infinitesimal Number of Municipalities’’? Who

would read it, beside the hard core?

That all states had borrowed too much

was a typical canard. Taking a look at

Moody’s annual State Debt Medians Report published in July of 2009, the author

could have seen that net tax-supported

debt per capita drops fairly quickly after

you look at the top 10 states. In first place

was Connecticut, at $4,490; in 10th was

California, at $1,805. In 30 of the states,

the figure was below $1,000.

A similar story could be told about public

pensions, as well as public employee pay.

A few states were bad at making their

actuarially-required contributions to their

pension systems. Some states and cities

had sweetened pensions, and salaries,

without much apparent regard of how to

pay for them.

And then there were some errors:

“Current bond issues will need to be

rolled over when they mature, since

budget gaps are rising.’’ Sheehan takes a

hallmark of the sovereign debt market and

transfers it to munis. That’s not how munis

work. Municipalities pay off their debts

over time, usually through the use of

serially maturing bonds. Yet this “rollover’’

error would be repeated.

Note here that Sheehan wasn’t talking

about the letters of credit or liquidity facilities backing variable-rate demand obliga-

tions expiring. This would become one of

the market’s typical non-issue issues in

2010 and 2011. As it turned out, the market

handled the, in Moody’s words, “unprecedented’’ number of expirations handily.

Sheehan wasn’t talking about VRDOs. He

was describing “the next Greece,’’ as critics

of the time put it.

“One of the largest municipal expenditures is coupon interest on bond obligations.’’ That’s not true. Debt service is

actually one of the smaller items in most

municipal budgets. As analysts would

eventually point out, why would public

officials go out of their way to anger the

investors they need and target debt service, since it would be of so little help in a

financial emergency?

Why did I go back and read “Dark Vision’’? Because more than a month after

it was published, it was mentioned on a

business news web site, which linked to

a piece on the Seeking Alpha blog, which

in turn linked to a piece on a Harvard Law

School blog, picking up approving comments from the uninformed every step of

the way.

And so the “coming collapse’’ of the municipal bond market had been announced.

In 2011, Bloomberg Brief: Municipal

Market’s Brian Chappatta asked Sheehan

what happened — why hadn’t the market

collapsed? He gave a very detailed response, which I include here as Appendix

2. I called him on Nov. 17 of this year, and

he gave me a very similar response: “One

thing I didn’t understand was how hard

states would work to pay their bonds so

they could continue to legislate. I thought

there’d be much more of a battle between

paying bonds and other expenses like

pensions. I still think that has to come at

some point, as the asset price bubble

starts to deflate. [States and municipalities] have continued to spend as if they

learned nothing from how close they did

come to defaulting in 2009.’’

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown 12

VI: Into The Abyss

The crush of news in 2009 meant that it

took a while for the market to confront the

municipal bond meltdown scenario being

presented. The Sheehan piece achieved

what I sensed was wide circulation, showing up around the Internet without much in

the way of rebuttal.

Sheehan was first. James Chanos,

noted short-seller, appeared in Barron’s

in the Nov. 9 “Current Yield’’ column:

“Dump Munis,’’ was the headline. The

culprit: “platinum-plated health-care and

retirement benefits,’’ said Chanos. I asked

Chanos on Nov. 17 if he had any further

thoughts about the municipal market, and

he declined comment.

On Dec. 16, 2009, Standard & Poor’s

published a paper entitled “Credit FAQ:

The Recession’s Impact on U.S. State and

Local Government Credit Risk.’’

I now see this as the first defense of

munis. Whether it was done in response

to Sheehan, I do not know.

The FAQ format is, of course, a feature

of the Internet; I’m not sure how much

circulation this piece got. It was detailed

and reasonable and accurate. But of

course Collapse trumps Muddle Along in

the Internet popularity stakes.

My favorite answer came in response

to the question: “Then why do state and

local governments keep talking about the

dire straits they are in?’’ S&P said: “As this

all plays out, we think that new headlines

will likely capture elected officials’ and oth-

ers’ efforts to make the public aware of the

circumstances of their austerity measures

and what they think will be the consequences of inaction.’’

Do the Right Thing

The important thing about the S&P

piece, as well as the earlier Moody’s

commentary tagging the entire sector with

a negative outlook, was that both rating

companies expected most public officials

to do the right thing by their bondholders.

Also noteworthy, especially in retrospect,

is how S&P took pains to say how “conditions do vary.’’ Once again: particular and

specific. It’s very much like that old legal

expression: all facts and circumstances.

Even in 2009, you could see several

themes playing out here. On the one

hand, you had outside critics saying that

municipalities were all in the same boat,

that they had exhausted their resources,

and that default and repudiation were

inevitable. On the other, you had analysts

saying that it was impossible to generalize about issuers, that most of them had

plenty of resources still available to them,

and that most of them could actively manage their way out of the situation.

The final piece of the puzzle appeared at

the very end of the year, although it didn’t

gain traction until later: a white paper by

Joshua D. Rauh of the Kellogg School of

Management at Northwestern University:

Are State Public Pensions

“Sustainable?

Why the Federal

Government Should Worry About

State Pension Liabilities.

”

— Title of paper by Joshua Rauh, Kellogg School

of Management at Northwestern University

“Are State Public Pensions Sustainable?

Why the Federal Government Should

Worry About State Pension Liabilities.’’

Of course, we all know what the answer

to the title’s question was.

This was a provocative piece of work.

Up to this point, as far as I know, nobody

had predicted that pension funds would

run out of cash altogether, or that pension underfunding might drive states “to

insolvency,’’ as Rauh claimed. Rauh also

introduced his notion that state and local

pension plans should “discount the benefit

cash flows at Treasury rates.’’

In other words, they should stop assuming that the assets they had put in

their pension systems would produce 8

percent a year. Discounting benefit flows

at Treasury rates produced a gap between

assets and liabilities of $3 trillion at the

end of 2008, Rauh wrote. He also modeled which states’ plans would run out of

money, and when.

Rauh’s chief assumption was that states

would contribute enough money to their

pension plans “to fully fund newly accrued

or recognized benefits at state-chosen

discount rates (usually 8 percent) but no

more.’’ This was “broadly in keeping with

states’ recent behavior.’’

The paper itself was no easy read, but

the “Table 1: When Might State Pension

Funds Run Dry?’’ was clear enough.

Rauh predicted that Illinois would run out

in 2018, Connecticut, Indiana and New

Jersey in 2019, Hawaii, Louisiana and

Oklahoma in 2020. Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New York and North Carolina would

never run out.

Rauh is now at the Stanford Graduate

School of Business. He didn’t respond to

a request for comment. He has continued

to publish, and his views are now wellknown. It used to be that public pension

funding was one of those things covered by rating companies perhaps on a

quarterly basis. Now, it seems that we get

regular, detailed updates on their condition almost weekly. This is a good thing.

People didn’t really start to discuss the

Rauh study until 2010. This would prove to

be the cauldron year for the muni meltdown.

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown 13

VII: Public Pensions

The year 2010 was

the peak year for

meltdown mongering.

It was as if with the real estate bubble

burst, banks failing and companies from

auto manufacturers to Wall Street brokerages in bankruptcy, gloomsters could

finally turn their attention to states and

municipalities.

Not all the material being published

about public finance was incendiary.

Some was salutary. As the old saying

goes, never waste a crisis. So it was with

public pensions. In February, the Pew

Center on the States published “The

Trillion Dollar Gap: Underfunded State

Retirement Systems and the Roads to

Reform,’’ a thoughtful, comprehensive 61page study.

Pew said the difference between what

states had on hand and the pension

and other retirement benefits they had

promised amounted to $1 trillion, and that

was conservative, because it was based

on June, 2008, data and thus hadn’t taken

into account all investment losses.

The Pew report was unhysterical and

exhaustive, filled with maps and tables of

data. It showed the extent of investment

losses, and ranked how the states were

managing the situation. On pensions, it

said, 16 were solid performers, 15 needed

improvement and 19 were “serious concerns,’’ while in the area of health care

and other benefits, which most states had

treated as a pay as you go expense, 9

were solid performers in terms of quantifying the obligation and putting aside money

for it. The report also noted that 15 states

in 2009 had passed legislation reforming

some aspect of their pension systems,

usually by making new employees contribute more.

As if any reminder were needed, the

results showed how the subject of public

pensions resisted generalization. New

York’s pensions were 107 percent funded,

Florida’s 101 percent. Illinois had only 54

percent of the money it needed, Kansas

59 percent, Colorado, 70 percent.

The study also examined investment

return assumptions, just then becoming a

fat target for critics. Recall that in September 2009, Pimco’s Bill Gross coined the

term the New Normal to characterize the

low-growth, low-yield future.

The Carolinas calculated they would

earn 7.25 percent, Colorado, Connecticut,

Illinois, Minnesota and New Hampshire

8.50 percent. By far the most states, 22,

were at 8 percent, which, as the report

pointed out, was the median investment

return for pension plans over 20 years.

The report examined the factors that

contributed to the $1 trillion gap, such as

the volatility of investments, states failing

to make their annual actuarially-required

contributions and “ill-considered benefit

increases’’ during good times. It also

examined the “road to reform.’’

Of course the Internet focused on the

“$1 trillion gap,’’ and even more on the

Rauh $3 trillion gap.

A subject that had received scant attention – except among the rating companies, municipal analysts, some local

newspapers, and the blog that since 2004

collected coverage of the topic, pensiontsunami.com – was now in the spotlight.

Public pension analysis was, almost, the

flavor du jour. At least three more academic reports on public pension liabilities

were published during the year.

‘Distinct Risk to Taxpayers’

In April, the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research presented resident scholar Andrew Biggs’s “The

Market Value of Public-Sector Pension

Deficits,’’ basically an endorsement of the

Rauh $3 trillion pension gap figure.

Then in June came a working paper by

Eileen Norcross and Andrew Biggs,

published by the Mercatus Center at

George Mason University entitled “The

Crisis in Public Sector Pension Plans:

A Blueprint for Reform in New Jersey.’’

Norcross and Biggs repeated the Rauh $3

trillion gap and advocated defined contribution over defined benefit pension plans.

The latter, they said, presented “a distinct

fiscal risk to taxpayers.’’

And in October, Rauh and Robert

Novy-Marx of the University of Rochester

produced a paper, “The Crisis in Local Government Pensions in the United

States’’ for a conference on retirement

and institutional money management

post-financial crisis. The authors looked

Source: Bloomberg/Andrew Harrer

‘The New Normal’: Bill Gross

at the unfunded pension obligations of

local governments, and concluded that,

if already-promised benefits were discounted at riskless, zero-coupon Treasury

yields, the total unfunded obligation for

the municipalities they studied was $383

billion rather than the $190 billion the

localities themselves calculated.

I was of two minds about the explosion

of interest in public pensions. On the one

hand, I thought it good to focus on the

subject, because it seemed that certain of

our elected representatives over time had

sweetened the salary and public pension pot in exchange for union peace and

votes, with no consideration for the way

even little enhancements add up. They

also all too often neglected to keep up

with their actuarially-required contributions

to their pension plans.

On the other hand, I objected to the “crisis’’ terminology which made it seem to the

uninitiated as if states and localities had

to come up with the money to fill the gaps

overnight. As always, I worried that generalizing about the subject was distracting.

What we really needed was focus: Which

states and municipalities had done the

worst jobs managing public pensions?

More importantly, why? These things

aren’t easy to trace, but glossing over the

subject in favor of big numbers lets the

guilty parties off the hook. What hapcontinued on next page...

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown 14

continued from previous page...

pened, when, why, and how can we guard

against it happening again?

It had taken almost

three decades, and the

dawn of the Internet

age, for me to realize

that data was not

definitive, that

analysts could make

the numbers dance.

Amplified Alarm

I think it was around this time, too, that

I became very skeptical of all “studies’’

and “reports.’’ It had taken almost three

decades, and the dawn of the Internet

age, for me to realize that data was not

definitive, that analysts could make the

numbers dance.

I also began growing impatient with

what I came to call the media’s “denominator problem.’’ Such-and-such costs “$3

BILLION dollars,’’ radio and television announcers would declare, all but reaching

a full windup to deliver the plosive “BILLION.’’ And that was fine. But it matters a

great deal if the “$1 BILLION’’ is part of a

budget, say, of $5 billion, or part of one

amounting to $50 billion or $150 billion.

We emphasize the numerator and ignore,

if we even know, the denominator.

In March, the National Association

of State Retirement Administrators

released two short but meaty reads,

the first on public pension plan investment return assumptions, the second

an analysis of the Rauh paper. Both

attempted to reassure readers that there

was a basis in fact for investment return

assumptions: Over a 20-year period,

median annualized investment returns

were 8.1 percent; over 25 years, 9.3 percent. In other words, the 8 percent return

assumptions prevalent among public

pensions weren’t fictional.

The analysis of the Rauh paper, “Are

State Public Pensions Sustainable?’’

said that the author ignored incremental

changes being made to improve the longterm sustainability of public pensions, and

that his central assumption, that states

would make contributions sufficient to

fund newly accrued or recognized benefits but no more, was unsupported by

current practice.

There was, it appeared, another side of

the story. How many Internet commenters

read it, I have no idea. Who cared about

the facts when alarm and exaggeration

could be echoed and amplified?

BloomBerg

Brief group

SuBScriptionS

Bloomberg newsletters are now available for group purchase

at very affordable rates. Share with your team, firm or clients.

contact us for more information:

+1-212-617-9030

bbrief@bloomberg.net

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown 15

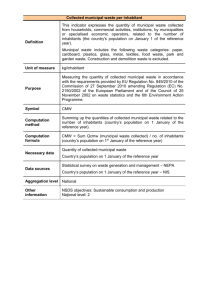

BLOOMBERG RANKINGS

Most Underfunded Pension Plans: States

RANK

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

20

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

49

STATE

Illinois

Kentucky

Connecticut

Alaska

Kansas

New Hampshire

Mississippi

Louisiana

Hawaii

Massachusetts

North Dakota

Rhode Island

Michigan

Colorado

West Virginia

Pennsylvania

New Jersey

Indiana

Maryland

South Carolina

Virginia

Alabama

Oklahoma

New Mexico

Vermont

Nevada

Ohio

Montana

Arizona

Arkansas

Minnesota

Utah

Missouri

California

Wyoming

Nebraska

Maine

Texas

Georgia

Iowa

Florida

Idaho

New York

Delaware

Oregon

Tennessee

Washington

North Carolina

South Dakota

Wisconsin

Median

FUNDING

RATIO 2013

%

39.3

44.2

49.1

54.7

56.4

56.7

57.6

58.1

60.0

60.8

61.0

61.1

61.3

61.5

63.2

64.0

64.5

64.8

65.3

65.4

65.4

66.2

66.5

66.7

69.2

69.3

71.9

73.3

74.1

74.5

74.7

76.5

76.6

76.9

78.7

79.2

79.6

80.4

80.6

80.7

80.8

85.5

87.3

88.2

90.7

91.5

95.1

95.4

99.9

99.9

69.3

FUNDING

RATIO 2012

%

40.4

46.8

49.1

59.2

59.2

56.2

57.9

55.9

59.2

65.3

63.5

62.1

65.0

63.2

64.2

65.6

67.5

61.0

64.2

67.9

69.5

66.9

64.9

63.1

70.2

71.0

65.1

63.9

74.5

71.4

75.0

78.3

78.0

77.4

79.6

78.2

79.1

82.0

82.5

79.5

81.6

84.9

90.5

88.3

82.0

91.5

93.7

95.3

92.6

99.9

68.7

FUNDING

RATIO 2011

%

43.4

50.5

55.1

59.5

62.2

57.5

62.1

56.2

59.4

71.4

68.8

62.3

71.5

61.2

58.0

71.7

68.1

64.7

64.5

66.5

72.0

70.1

66.7

67.0

72.5

70.1

67.8

66.3

73.2

72.5

78.4

82.8

81.9

78.4

83.0

81.9

80.2

82.9

84.7

79.5

82.3

90.2

94.3

90.7

86.9

89.9

94.9

96.3

96.3

99.9

71.6

FUNDING

RATIO 2010

&

45.4

54.3

53.4

60.9

63.7

58.7

64.0

55.9

61.4

68.7

72.1

61.8

78.8

66.1

56.0

77.8

66.0

66.5

63.9

68.7

79.7

73.9

55.9

72.4

74.6

70.5

67.2

70.0

77.0

74.8

79.8

85.7

77.0

80.7

85.9

83.8

70.4

83.3

87.1

81.0

83.7

78.6

101.5

92.0

85.8

89.9

92.2

96.8

96.1

99.8

74.3

FUNDING

RATIO 2009

%

50.6

58.2

61.6

75.7

58.8

58.5

67.3

60.0

64.6

63.8

83.4

64.3

83.6

70.0

63.7

85.5

71.3

72.3

64.9

70.1

83.5

75.1

57.4

76.2

72.8

72.4

66.8

74.3

79.9

77.5

77.1

84.1

79.4

86.6

88.8

87.9

72.6

84.1

91.6

80.9

84.1

73.9

107.4

94.4

80.2

95.1

93.9

99.3

91.7

99.8

75.9

FUNDING

RATIO 2008

%

54.3

63.8

61.6

74.1

70.8

68.0

72.8

69.6

68.8

80.5

87.0

59.7

88.3

69.8

67.6

86.9

76.0

69.8

77.7

71.1

81.8

79.4

60.7

82.8

87.8

76.2

86.0

83.4

80.8

87.2

81.4

100.8

82.9

87.6

79.3

92.0

79.7

90.7

94.6

88.7

101.7

93.2

105.9

98.3

112.2

95.1

92.9

103.4

97.4

99.7

82.3

MEDIAN

%

44.4

52.4

54.3

60.2

60.7

58.0

63.1

57.2

60.7

67.0

70.5

62.0

75.2

64.7

63.5

74.7

67.8

65.7

64.7

68.3

75.9

72.0

62.8

69.7

72.7

70.8

67.5

71.7

75.7

74.6

77.7

83.4

78.7

79.5

81.3

82.8

79.3

83.1

85.9

80.8

83.0

85.2

97.9

91.3

86.4

91.5

93.8

96.3

96.2

99.9

73.0

For the fourth year in a row,

Illinois, Kentucky and Connecticut top the list of most

underfunded pension plans

METHODOLOGY:

Bloomberg ranked U.S.

states based on their pension

funding ratios in 2013. The

Bloomberg municipal data and

municipal fundamentals teams

collected and supplemented

data from each state’s Comprehensive Annual Financial

Report, a set of government

financial statements. Data are

for individual states’ respective

fiscal year-ends as of the date

of publication of the CAFR.

Supplemental pension reports

intended to augment a particular year’s CAFR were added

to that year’s fundamentals.

Fiscal year-end of supplemental pension reports may

differ from the state’s CAFR.

All other reports were carried

forward to the next fiscal year.

The funding ratio provides

an indication of the financial

resources available to meet

current and future pension

obligations. Percentages were

calculated by dividing the actuarial value of plan assets by

the projected benefit obligation. Where specific data were

missing in the consolidated

reported totals, the pension

funds were contacted directly.

The District of Columbia

had a funding ratio of 103.6%

in 2013.

Source: Bloomberg

AS OF: October 2, 2014

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown 16

VIII: Media Frenzy

Source: Svein Erik Dahl/John Wiley & Sons

Christopher Whalen

It wasn’t long before it

seemed like everyone

was talking about a Muni

Meltdown. The following is a by

no means exhaustive list of some of the

alarming stuff published on munis in 2010.

I’m not including the bloggers who at this

point were advocating defaulting on bonds

on behalf of “the taxpayers’’ or “clickbait’’

compilations like “The 10 Cities That Will

NEVER Come Back’’ that were such a

favorite of Business Insider at the time. I

should note here that Joe Weisenthal,

then of Business Insider, now works for

Bloomberg as Digital Content Officer.

Consider this, from the newspaper of record:

“California, New York and other states are

showing many of the same signs of debt overload that recently took Greece to the brink

— budgets that will not balance, accounting

that masks debt, the use of derivatives to plug

holes and armies of retired public workers

who are counting on benefits that are proving

harder and harder to pay.’’

Greek Myths

The story appeared on Page One of the

March 30 New York Times, headlined,

“State Debt Woes Grow Too Big to Camouflage.’’ Reporter Mary Williams Walsh

continued, “Some economists fear the

states have a potentially bigger problem

than their recession-induced budget woes.

If investors become reluctant to buy the

states’ debt, the result could be a credit

squeeze, not entirely different from the

financial markets in Europe, where markets were reluctant to refinance billions in

Greek debt.’’

Then there was the April blog posting by

Rick Bookstaber, a senior policy adviser

at the SEC. The next big crisis was the

municipal market, he wrote. The culprit:

overleverage, “in the form of high pension

benefits and post-retirement health care.’’

He observed: “Once a few municipalities

default, there is a risk of a widespread

cascade in defaults because the opprobrium will be lessened, all the more so if the

defaults are spurred by a taxpayer revolt —

democracy at work.’’

Bookstaber was among those asked by

Brian Chappatta at the end of 2011 about

what happened. His response is contained

in Appendix 2. I chatted with Bookstaber,

who now works for the U.S. Treasury in

the Office of Financial Research, in midNovember, and he told me he had nothing

to do with the muni market, and declined

further comment.

I knew we had reached an entirely different level of muni crisis coverage when

Matt Taibbi of Rolling Stone, who had

achieved a certain notoriety in 2009 when

he likened Goldman Sachs to “a giant

vampire squid wrapped around the face

of humanity,’’ weighed in with an article

entitled “Looting Main Street’’ in the April

15 edition of the magazine.

The Taibbi piece concerned Jefferson

County, Alabama’s use of interest-rate

swaps, and was subtitled, “How the nation’s biggest banks are ripping off American cities with the same predatory deals

that brought down Greece.’’ The message

was that municipalities were “now reeling

under the weight of similarly elaborate and

ill-advised swaps,’’ which the author termed

a “financial time bomb.’’

It had been quite a few years since I had

read Rolling Stone. I’ve been pretty exercised about municipalities’ use of swaps,

myself. I’m not sure how many Americans

get their investing advice from Rolling

Stone, but they couldn’t have found comfort

in yet another tale of predatory Wall Street

and feckless or corrupt public officials.

The right-leaning Manhattan Institute’s

Nicole Gelinas in the think-tank’s City

Journal advised readers of the Spring 2010

issue to “Beware the Muni-Bond Bubble.’’

Gelinas wrote: “Investors in municipal

bonds don’t have to worry about a thing,

the thinking goes, because the states and

cities that issue them will do anything to

avoid reneging on their obligations — and

even if they fail, surely Washington will step

in and save investors from big losses.’’

She continued: “These are dangerous

assumptions. Just as with mortgages, the

very fact that investors place unlimited faith

in a market could eventually destroy that

market. If investors believe that they take

no risk, they will lend states and cities far

too much — so much that these borrowers won’t be able to repay their obligations

while maintaining a reasonable level of

public services. The investors, then, could

help bankrupt state and local governments

— and take massive losses in the process.’’

Interesting Point of View

This was, I thought, an interesting point

of view. And then: “The uncomfortable truth

is that as municipal debt grows, the risk

mounts that someday it will be politically,

economically, and financially worthwhile for

borrowers to escape it,’’ Gelinas wrote.

Four years on, I asked Gelinas about the

relative resilience of the market. In an email dated Nov. 16, she replied, “The ‘resilency’ is shallow. Pension funds are doing

well because [of] the Fed’s extraordinary

actions to push up asset prices. But

around the nation, from state-level credits

such as Illinois and New Jersey to rich

cities like New York to poorer and smaller

cities and towns all over the place, many

places are still pretty much insolvent,’’

she wrote. “They cannot make good on

the healthcare promises they have made

to current and future retirees, and many

will not be able to make good on their

promises to pensioners. In the meanwhile,

infrastructure deteriorates because money

that should be going to the future is going

to the past. The 2009 recovery act was a

missed opportunity to help states, cities,

and other municipal credits fix their longterm structural problems, mostly pensions

and health promises, in return for immedicontinued on next page...

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown 17

continued from previous page...

ate cash; instead, Washington treated it as

a cyclical revenue shortfall.’’

She continued, “That we haven’t seen

bondholder panic is more a sign of the

desperation for yield and the principalagent problem (do retail investors really

know the risks that they are taking or do

they see bonds as ‘safe’). It’s harder today

than it was five years ago to assess the

“too-big-to-fail risk” — that is, it is unclear

whether Washington would step in to

save, say, Citigroup bondholders, this time

around, and it is similarly unclear whether

Washington would step in to save, say,

Illinois or New Jersey bondholders or pensioners. In the end, the clearest action that

Congress takes may — or may not — be in

not bailing out Puerto Rican bondholders. ‘‘

Warren Buffett opined on the muni

market at least twice in 2010, telling

shareholders at the Berkshire Hathaway

annual meeting in May, “It would be hard

in the end for the federal government to

turn away a state having extreme financial

difficulty when they’ve gone to General

Motors and other entities and saved them.’’

In June, Buffett appeared before the U.S.

Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission and

predicted a “terrible problem’’ for municipal

bonds “and then the question becomes will

the federal government help.’’

Buffett hasn’t moderated in his views. In

the Feb. 28, 2014 letter to Berkshire shreholders, he wrote: “Local and state financial

problems are accelerating, in large part

because public entities promised pensions

they couldn’t afford. Citizens and public

officials typically under-appreciated the

gigantic financial tapeworm that was born

when promises were made that conflicted

with a willingness to fund them.’’

On June 14 of 2010, Ianthe Jeanne

Dugan wrote in the Wall Street Journal

that investors were “ignoring warning signs’’

in the municipal market. The article was

headlined, “Investors Looking Past Red

Flags in Muni Market.’’

James Grant — a friend, for whom

I worked from 1994 to 1999 — offered

another take on repudiation in the June

25 Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, in a

scholarly article headlined, “Concerning

the American Repudiation Gene.’’

“So low are yields, so complacent are

investors, so persistent are fiscal deficits,

so heavy is the weight of post-retirement

employee benefits and so ill-equipped

are mutual funds to deal with anything

resembling a shareholders’ run that we are

prepared to take the analytical leap. On the

length and breadth of the muni market, we

declare ourselves bearish,’’ wrote Grant.

“The repudiation gene is ever present,’’

Grant continued, well into a very scholarly

article. “The question is whether circumstances in the tax-exempt market may coax

it out of latency and back into action.’’

I asked Jim about his call this year. On

Nov. 17, he e-mailed: “A swing and a miss.

Source: Bloomberg/Ramin Talaie

‘American Repudiation Gene’: James Grant

The muni market has continued to mosey,

there was no run on mutual funds. Perhaps

more to the point, there turned out to be

no homogeneous market on which to be

comprehensively bearish. What’s Paul

Isaac’s line?’’

Grant continued: “As to surprises: Where

we erred was in expecting surprises. The

muni market has not surprised. No drama,

no short-selling, no credit upheaval, no

volatility to speak of.’’ He concluded: “As to

the current Grant’s stance toward munis,

we judge that yields are too low. In that

they resemble yields nearly everywhere.’’

‘A Muni-Bond Bomb’

On Aug. 23, Steve Malanga of the

Manhattan Institute wrote an OpEd piece

in the Wall Street Journal about the SEC

charging the state of New Jersey with fraud

for misleading investors; the article was

entitled, “How States Hide Their Budget

Deficits,’’ and implied that other states may

be guilty of the same thing.

Malanga also had a story in the Summer 2010 edition of City Journal, “How

to Dismantle a Muni-Bond Bomb.’’ He

wrote: “State and local borrowing, once

thought of as a way to finance essential

infrastructure, has mutated into a source of

constant abuse. Like homeowners before

the housing bubble burst, states and cities

have gorged on debt, extended repayment

times, and used devious means to avoid

limits on borrowing — all in order to finance

risky projects and kick fiscal problems

down the road.’’

He offered a handful of reforms, and said

if the state and local debt bomb “can’t be

defused, we’re all at risk.’’

I chatted with Malanga about the lack

of a muni explosion since then in midNovember of this year. He noted that

rating companies were now putting much

more weight to pension debt in assessing credit, and, “What we’re seeing is a

little more skepticism in the marketplace

because of what happened in Detroit.’’ He

added, “It’s a very uncertain time’’ for the

municipal market.

In September, Meredith Whitney produced “The Tragedy of the Commons,’’ a

report on the 15 largest states. This would

have gotten a lot splashier coverage when it

appeared had Whitney actually published it.

As it was, she sent out a press release,

but refused to show it to anyone but clients.

I asked for a copy and was told I’d have to

pay for it.

Seeking Refuge

Whitney at the time said she had spent

two years working on the report, which

didn’t predict any state defaults. Yet she

began making the rounds, appearing on

business radio and television and warning

about how overleveraged states were, and

how they needed a federal bailout. In the

Nov. 3, 2010 Wall Street Journal, she wrote

an OpEd piece entitled, “State Bailouts?

They’ve Already Begun.’’

On Oct. 5, the New York Times’s Mary

Williams Walsh wrote about how Harriscontinued on next page...

Front page | Previous page | Next page

11.25.14 www.bloombergbriefs.com

Bloomberg Brief | Muni Meltdown 18

continued from previous page...