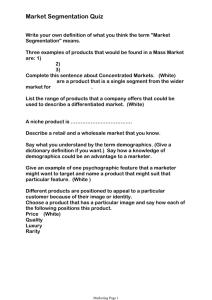

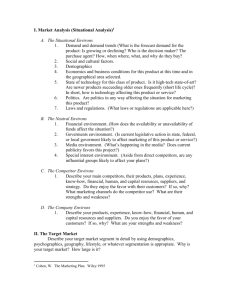

TCRP Report 36: A Handbook: Using Market Segmentation to

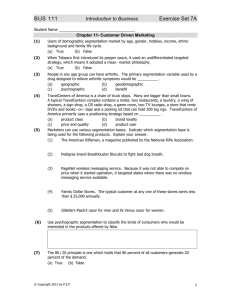

advertisement